As the Year of the Tiger gives way to the Year of the Rabbit, the perennial debate resurfaces: Are the Chinese zodiac’s 12 animals a homegrown tradition or imported from abroad? Ancient civilizations like Egypt, Babylon, India, and Greece had similar systems, fueling theories of foreign origins. Yet, textual and archaeological evidence firmly roots the Chinese zodiac in native soil, dating back at least 2,800 years to the Zhou Dynasty. Let’s unpack the facts.

Global Parallels: Coincidence or Diffusion?

The 12 zodiac animals aren’t uniquely Chinese. Ancient Babylon featured bull, goat, lion, donkey, scarab, snake, dog, cat, crocodile, flamingo, monkey, and eagle. Egyptian and Greek versions swapped the scarab for crab; Greeks changed cat to mouse. India’s lineup—rat, bull, lion, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, garuda, dog, pig—closely mirrors China’s, save for lion and garuda.

Scholars like French sinologist Édouard Chavannes (1906) argued origins in Turkic or Western regions. Guo Moruo (1929) linked it to Babylonian zodiac constellations transmitted via Central Asia. Former Xinjiang Academy head Li Shuhui claimed it “likely imported.” These views persist, but evidence tells a different story.

Zhou Dynasty Proof: Textual Evidence from 2,800+ Years Ago

No Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE) records confirm the zodiac—oracle bones lack mentions. By the Zhou (1046–256 BCE), it’s unmistakable:

- Shijing (Book of Songs), Xiaoya: Jiri: “On the auspicious day gengwu, I select my horses.” Here, wu pairs with horse—a clear zodiac link. The poem describes King Xuan of Zhou’s (r. 827–782 BCE) hunt, placing the tradition over 2,800 years ago.

- Zuo Zhuan (Chronicle of Zuo): During Duke Xiang of Lu’s reign (572–542 BCE), Chen state figures Qing Hu and Qing Yin appear—names evoking tiger (hu) and tiger (yin). Scholars interpret this as “linked naming” for siblings, implying zodiac familiarity.

- Lüshi Chunqiu (Spring and Autumn Annals of Lü Buwei): “In the last winter month, send out earth oxen to dispel cold.” The 12th month is chou (ox month), aligning with the zodiac sequence (1st: yin tiger, etc.).

These classics prove the zodiac’s existence by the Western Zhou, predating claimed foreign influences.

Qin Dynasty Artifacts: Zodiac Nearly Finalized

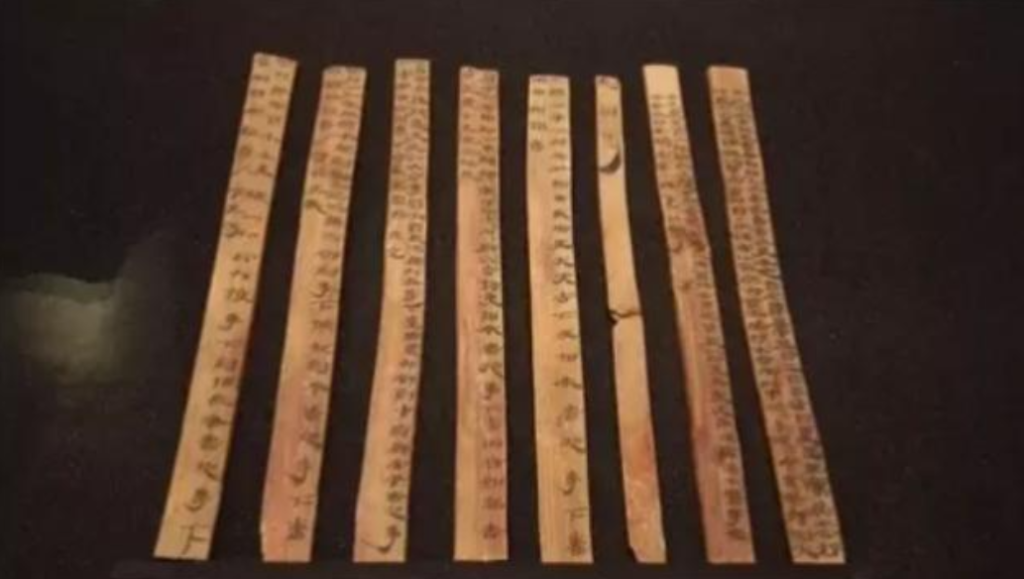

Archaeology cements this:

- 1975 Yunmeng Shuihudi Qin Slips (Rizhe: Daozhe): A near-complete zodiac lists animals matching later versions, though chen lacks one, wu is deer (not horse), wei horse (not goat), xu old sheep (not dog). This suggests regional variations or an evolving system.

- 1986 Fangmatan Qin Tomb Slips (Types A/B Rishu): Fully matches modern zodiac except minor errors (chen chong likely “dragon” as ancient term for insect; si ji probable scribe mistake for chicken in you).

Both date to the Qin (221–206 BCE), pushing origins to the Spring and Autumn or Warring States periods. Differences reflect local fauna—e.g., deer common in some areas.

Why Native? Evidence Trumps “Alleged” Foreign Claims

Foreign systems are “said to” predate China but lack verifiable texts or artifacts. Babylon’s zodiac ties to constellations, not daily animals; no proven transmission to China.

Key arguments for indigenous roots:

- Solid Proof vs. Hearsay: China’s zodiac boasts Shijing inscriptions and Qin slips—tangible, dated evidence spanning ~2,800–3,000 years. Foreign claims rely on speculation without equivalents.

- Local Animals, Local Logic: Each culture’s zodiac features native species. China’s includes dragon (absent elsewhere except India, where archaeology traces it to 8,000-year-old Chinese motifs). No exotic imports like Babylon’s scarab appear in Chinese records.

Parallel evolution from agrarian needs (calendars, divination) is likely, but China’s documented continuity stands unchallenged. Future digs could refine this—perhaps uncovering Shang evidence—but current facts affirm a native Chinese zodiac.

References

- Britannica. (2023). Zodiac: Ancient Systems.

- Needham, J. (1959). Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press.

- Chavannes, É. (1906). Les douze animaux des années dans l’Asie centrale. T’oung Pao.

- Guo Moruo. (1929). Shi Gan Zhi. In Collected Works.

- Li Shuhui. (2010s). Public Statements on Zodiac Origins (Archived Interviews).

- Oracle Bone Inscriptions Database. (2023). Shang Dynasty Records.

- Shijing (Book of Songs). Xiaoya: Jiri. Translated by Legge, J. (1871).

- Zuo Zhuan. Duke Xiang Years 7, 20, 23. Translated by Durrant et al. (2016).

- Lüshi Chunqiu. Seasonal Chapters. Translated by Knoblock & Riegel (2000).

- Shuihudi Qin Slips. (1975). Yunmeng Excavation Report. Cultural Relics Press.

- Fangmatan Qin Slips. (1986). Gansu Provincial Museum Report.

- Porter, D. (1996). From Deluge to Discourse: Myth in Early China. SUNY Press.

- Mesopotamian Astrology Records. (c. 1800 BCE). British Museum Archives.

- Allen, R. H. (1899). Star Names and Their Meanings.

- Major, J. S. (1993). Heaven and Earth in Early Han Thought. SUNY Press.

- Hongshan Culture Dragon Artifacts. (c. 6000 BCE). Liaoning Provincial Institute.