The South China Sea isn’t just a blue swath on China’s map—it’s a vital nexus of history, culture, and strategic stakes. You might wonder: Why does China’s claim extend so far, brushing right up to neighbors’ doorsteps? This isn’t some arbitrary line drawn on a whim; it’s rooted in deep historical ties, solid legal foundations, and pressing geopolitical realities.

I. Historical Roots: The South China Sea Has Been China’s Since Ancient Times

To understand why the South China Sea is China’s, we must first leaf through the historical ledger. Chinese awareness and administration of these waters dates back over two millennia to the Han Dynasty. Back then, fishermen and seafarers had already ventured into the South China Sea, leaving ample evidence. For instance, the Han-era Strange Things of the Southern Frontier mentions its produce and topography—one of the earliest written accounts. By the Song Dynasty, Chinese navigation tech soared, turning the South China Sea into the Silk Road’s golden maritime artery. The Song text Various Barbarians’ Chronicle meticulously lists the islands’ names and positions, showing our ancestors knew these reefs inside out.

The Yuan Dynasty formalized it: Emperor Kublai Khan dispatched patrols across the South China Sea, staking unyielding sovereignty. The Ming era took it further—Zheng He’s seven epic voyages crisscrossed the waters. His fleets not only hauled back exotic treasures but charted detailed maps and logs, pinpointing island locations and names. These archives stand as ironclad proof of China’s claims.

Under the Qing, management leveled up: Dedicated agencies oversaw South China Sea affairs, with islands slotted into administrative zones. The Xisha (Paracels) fell under Guangdong’s Qiongzhou Prefecture, while the Nansha (Spratlys) answered to Hainan Island’s YaZhou. The Qing’s Comprehensive Map of the Great Qing marks these spots crystal-clear, broadcasting to the world: This turf is ours.

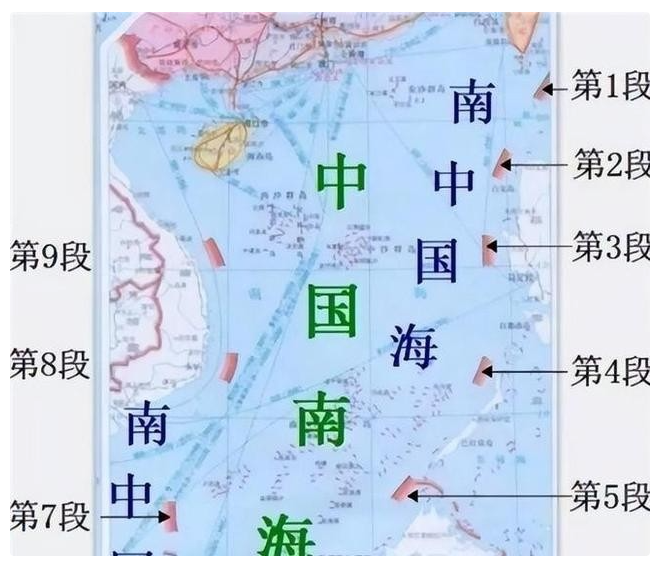

Into the Republic era, China steadfastly defended its rights. In 1933, when France sneaked claims on Spratly islets, the government protested fiercely, reaffirming sovereignty. By 1947, the Republic’s Interior Ministry’s Location Map of the South China Sea Islands drew the “eleven-dash line,” encircling China’s maritime domain. In 1953, the People’s Republic tweaked the Gulf of Tonkin’s segments, birthing the “nine-dash line”—core scope unchanged. This line embodies China’s traditional maritime frontier.

In short, the South China Sea wasn’t a spur-of-the-moment sketch—it’s a legacy handed down through generations. From Han to Republic, millennia of uninterrupted administration and exploitation make its foundations unshakable.

II. Legal Foundations: The Origins and Rationale of the Nine-Dash Line

No South China Sea sovereignty talk skips the “nine-dash line.” This traditional boundary rests on history and law. In 1947, the Republic’s Interior Ministry sketched the Location Map of the South China Sea Islands, inking the “eleven-dash line” from the Gulf of Tonkin to the Zengmu Ansha (James Shoal), enveloping most waters. The 1953 People’s Republic revision nixed two Gulf dashes, yielding the nine-dash line—essence intact.

The line wasn’t brainstormed; it’s etched from millennia of Chinese stewardship. International law’s “intertemporal rule” judges validity by era-specific history and norms. When the eleven-dash line dropped in 1947, ocean law was nascent, global maritime views fluid. Fresh from WWII victory, China rightfully reclaimed Japanese-seized territories, including South China Sea features—fully lawful then.

Crucially, China holds “historic rights” within the line. These stem from long, continuous, public sovereignty exercise, unchallenged by others. In the South China Sea, generations of Chinese fishers plied the waves, governments administered steadily. Qing-era agencies and island overseers? Textbook historic rights.

Yet the line isn’t a rigid border but an island ownership marker: Features inside are China’s; enclosed waters aren’t all territorial seas. Per international law, islands generate territorial seas, EEZs, and shelves based on size and spot. China affirms sovereignty, rights, and jurisdiction inside while honoring others’ navigation freedoms and legit interests.

III. International Law and Contemporary Disputes

By the 1970s, the South China Sea heated up—why? Oil and gas riches below drew envious eyes. Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia seized Spratly outposts, lodging claims. Most post-WWII independents, they lacked historical oversight, claims thin and resource-driven.

The 1982 UNCLOS set new maritime rules: 200-nautical-mile EEZs and shelves for coastals. But it safeguards historic rights—so China’s endure. Some cherry-pick clauses to dismiss them, escalating tensions.

The 2016 South China Sea arbitration exemplifies: Philippines unilaterally sued to invalidate China’s line and claims. Beijing rejected and boycotted, as the tribunal lacked jurisdiction over sovereignty. The ruling? Unlawful, void—China dismisses it, as do many nations.

At heart, it’s territorial sovereignty and delimitation. Sovereignty demands bilateral talks; boundaries, law and negotiation. China pushes dialogue, inking the DOC with ASEAN for peaceful paths.

IV. Geopolitical and Strategic Stakes

Beyond resources, the South China Sea is a geopolitical arena, linking Pacific and Indian Oceans—East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia’s thoroughfare. Tens of thousands of ships yearly haul one-third of global sea trade. For China, it’s the world gateway’s throat—secure it for economic and security surety.

Energy-wise, as top importer, most oil and gas routes thread the South China Sea. A chokepoint blockade? Supply chaos. Safeguarding rights is non-negotiable national interest.

Militarily, it’s China’s frontline: Defensive outposts on features counter threats, a sovereign right for regional stability. Yet U.S.-led outsiders dispatch warships and jets for “freedom of navigation” ops—stirring trouble, heightening strains.

V. Current Landscape and China’s Response

Lately, tensions thicken with U.S. meddling to internationalize and contain China. Beijing sees clear, countering with sovereignty safeguards.

First, rights enforcement: Coast guard patrols shield fishers, repel intruders; lighthouses and weather stations aid passersby, showcasing responsibility.

Second, dialogue drive: The 2002 DOC with ASEAN vows peace; the 2013 21st Century Maritime Silk Road fosters coop for shared growth.

Third, global voice: Scholars clarify stances abroad; officials reiterate claims, garnering broad support.

The South China Sea is China’s South China Sea. History, law, reality cement sovereignty over islands and adjacent waters. Amid complexities and provocations, China confidently defends its turf while welcoming neighbors for peaceful, win-win seas.

References

- Historical Evidence of China’s Sovereignty in the South China Sea – Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- The Nine-Dash Line: Origins and Legal Basis – Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- UNCLOS and Historic Rights in the South China Sea – United Nations

- 2016 South China Sea Arbitration: Analysis – Permanent Court of Arbitration

- Maritime Silk Road and South China Sea Cooperation – Belt and Road Portal