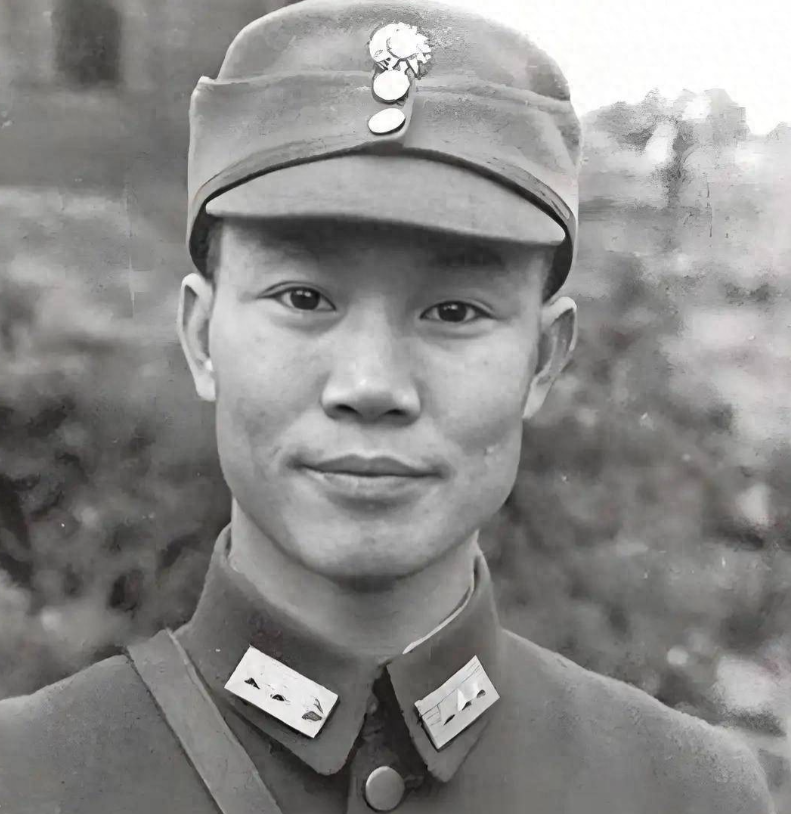

On a quiet morning in June 1950, a gunshot echoed across Taipei’s Machangding, sealing Wu Shi’s fate with a label — “Communist spy.” That same day, his 16-year-old daughter Wu Xuecheng was expelled from her dormitory, while his 7-year-old son Wu Jiancheng stood at the alley’s end, clutching a chipped enamel bowl. Etched inside the bowl was a single character — “Shi”, carved by his father’s hand. No one dared to shelter them. Even the family’s former neighbors locked their doors tight in fear.

Two weeks later, however, the orphaned siblings quietly moved into a small Japanese-style wooden house on Heping East Road. The stove always had warm porridge, and a red-paper-wrapped household registration booklet sat in the drawer. In the guardian column was a new name — Chen Mingde.

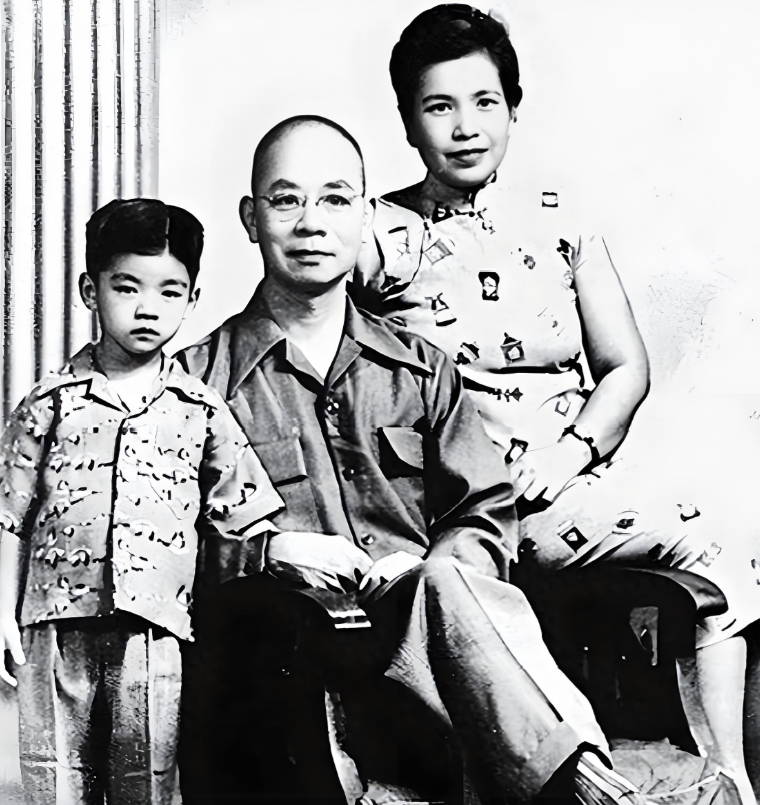

That name was a disguise. Chen Mingde was none other than Chen Cheng, the powerful “Little Generalissimo,” second only to Chiang Kai-shek. Gravely ill, he once called his adjutant Wu Yinxian to his bedside and whispered, “Old Wu saved my life; I’ll protect his children.” It was a soft promise, more like a cough than a command — but it lasted fifteen years. Each month, 200 New Taiwan Dollars were discreetly transferred from a “special office fund,” at a time when most workers earned only 60. Wu Shi’s wife Wang Biqui had her nine-year prison sentence quietly suspended. The younger Wu was enrolled in Jianguo High School, with registration forms signed by Madam Tan Xiang, Chen’s wife. No document bore Chen’s name, yet every detail was handled flawlessly.

Chiang Ching-kuo Knew Everything — and Chose Silence

By 1950, Chiang Ching-kuo had just taken charge of the Presidential Office’s Confidential Data Section. His intelligence network — the Bureau of Investigation, the Security Command, and the Military Police — reported everything. Three separate memos landed on his desk, each confirming: “Chen Mingde is Chen Cheng.”

Chiang quietly locked the files in a drawer and wrote four words: “Temporarily not to be handled.”

Many believed he feared Chen’s influence, who still commanded tens of thousands of loyal “civil engineering” officers. But Chiang’s real concern was the morale of the army. Wu Shi had once compiled the Military Dictionary still used in academies, fought at Changsha and Kunlun Pass during the Anti-Japanese War. If the regime persecuted his children, what message would that send to soldiers who had fought beside him?

A Calculated Balance Between Fear and Humanity

There was also a deeper political calculus — one neither Chiang Kai-shek nor Chiang Ching-kuo ever said aloud.

Executing Wu Shi was a gesture to Washington, proof of the regime’s anti-Communist resolve. But if they had punished his children too, the world would have branded them as tyrants. By allowing Chen Cheng to play the benevolent protector, while Chiang himself played the enforcer, they crafted a dual image — justice in form, mercy in substance.

In his diary, Chiang Ching-kuo later wrote:

“Vice Premier Chen’s actions are improper in office, yet understandable in sentiment. If exposed, the enemy would rejoice, and we would regret.”

With that, the case was buried.

Quiet Acts of Kindness in a Harsh Era

In 1956, when young Wu Jiancheng fell gravely ill with pneumonia, hospitals refused him for being the child of a “traitor.” At midnight, Chen Cheng’s driver carried him to a private clinic under the alias “Chen Mingde’s son.” When the intelligence office later reported this to Chiang Ching-kuo, he merely replied, “Noted,” and filed the report away under “General Information.” Even Mao Renfeng, head of the secret police, never saw it.

By 1965, as Chen Cheng lay dying, he handed his aide a final check for 2,000 dollars and an unsealed letter. “If the Wu children ever need help after I’m gone, give them this,” he said weakly. The letter read only:

“Brother Wu Shi, I have done my utmost.

Let your children take care of themselves.

— Mingde.”

At Chen’s funeral, Chiang Ching-kuo stood silently in the back. When asked whether to destroy the old “Chen Mingde” files, he shook his head.

“Keep them,” he said softly. “Let the future see — we did something human, too.”

That faint sigh cracked open a narrow slit in the iron gate of the White Terror era — not letting in light, but revealing a flicker of shared humanity between two men trapped in politics’ cruel machinery.

The Debt of a Lifetime

Years later, Wu Jiancheng went to study in the United States. For the first time, his passport listed his true guardian — Chen Cheng. When the visa officer asked about their relationship, he simply said, “A friend of my father.”

That single word — “friend” — carried the weight of a lifetime.

When the archives were declassified in 2000, Taiwan’s Academia Historica released the evidence: remittance slips, school records, hospital bills — all under the name “Chen Mingde.” Journalists tracked down the elderly Wu Xuecheng, who said quietly,

“It turns out, we owed Uncle Chen our lives.”

Chiang Ching-kuo never spoke of it again. But in a 1970 transcript of a private meeting, he left one final line that explained it all:

“Politics must make people fear — but also let them live.

If they only fear, and cannot live, the whole system collapses.”

In that sentence lies the truth of why Chiang turned a blind eye — a rare moment when power, guilt, and humanity briefly coexisted in the shadows of history.