On February 17, 2008, a new entity appeared on Europe’s map: Kosovo. It declared independence without Serbia’s consent or United Nations authorization, backed by NATO’s military umbrella. The world reacted sharply—Western powers like the US, UK, and France swiftly recognized it, while Russia, China, and India stood firm in opposition. Fast-forward 17 years to 2025, and out of 193 UN member states, 108 (over half) now acknowledge Kosovo’s sovereignty. Yet China remains unmoved, holding the line on non-recognition. Why does Beijing cling to this stance for a “state” that’s endured nearly two decades?

A Millennium-Old Destiny Clash: The Heart of the Serbia-Kosovo Conflict

To grasp Kosovo’s sensitivity for China, delve into its profound historical roots. For Serbs, Kosovo isn’t mere territory—it’s a sacred cradle of their nation. The pivotal Battle of Kosovo on June 28, 1389, saw Serbian Prince Lazar lead a Christian coalition against Ottoman Sultan Murad I. Though fierce, with the Sultan slain, the Serbs fell, ushering in nearly 500 years of Ottoman dominion.

This defeat etched itself into Serbian collective memory as a heroic tragedy. Lazar became a martyr, the Kosovo field a “site of sacrifice,” commemorated annually on Vidovdan (June 28). Serbs view Kosovo as the “cradle of Serbia,” a bastion of Orthodox Christianity, and the soul of their ethnicity. Conversely, for Kosovo Albanians (Albanians), it’s equally ancestral soil.

Albanians trace roots to the ancient Illyrians, Europe’s oldest indigenous group, inhabiting the region since Roman times—predating Slavs by nearly a millennium. Under Ottoman rule, many Albanians converted to Islam for social perks and tax breaks, while Orthodox Serbs often migrated north to preserve their faith. This “faith divide” reshaped demographics: by the 20th century, Albanians surged to over 90% of the population, from a minority foothold.

Initially, Serbs and Albanians weren’t foes; they allied against Ottoman incursions. Post-defeat, paths diverged—one exiled for faith, the other adapted to survive. Serbs saw Albanian conversions as betrayal of Christendom; Albanians resented Serbian dominance. Resentment simmered in history’s folds, fueling the Serbia-Kosovo conflict.

From Yugoslavia’s Collapse to NATO’s Bombardment

Kosovo’s woes transcend ethnic rifts—it’s a great-power chessboard. Post-WWII, Tito’s Yugoslavia pursued non-alignment, shunning both Soviet and US blocs while enforcing “Brotherhood and Unity” to curb nationalism and forge a “Yugoslav” identity.

This suppression bottled tensions like a pressure cooker. Tito’s 1980 death unleashed chaos. Republics like Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia sought secession; Kosovo, as Serbia’s autonomous province, stirred for independence. In 1989, Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević revoked Kosovo’s autonomy under the banner of Serbian interests, igniting Albanian fury. They formed a “parallel government” for non-violent resistance.

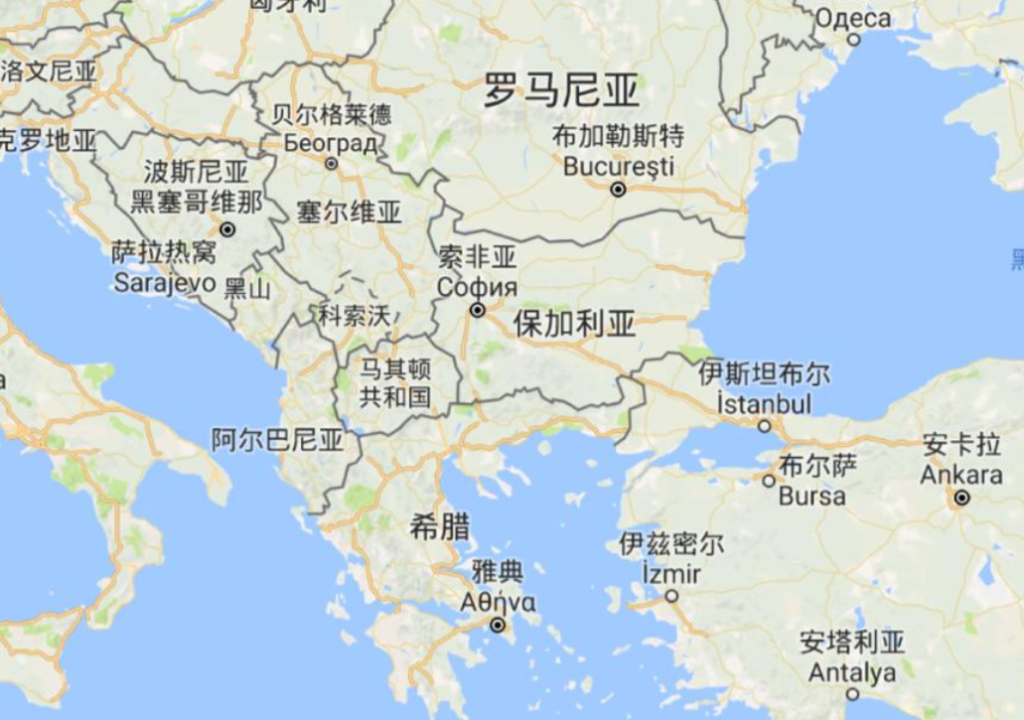

By 1998, clashes escalated: the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) battled Serbian forces, causing heavy casualties and refugee crises. Western media amplified “humanitarian catastrophe” claims of Serbian “ethnic cleansing.” On March 24, 1999, NATO bombed the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia-Montenegro) without UN Security Council approval—a 78-day campaign killing over 2,500, injuring 12,500, and ravaging infrastructure.

China’s outrage peaked on May 7, 1999, when NATO missiles struck Beijing’s embassy in Belgrade, killing three journalists: Shao Yunhuan, Xu Xinghu, and Zhu Ying. This transformed China’s view: not a noble intervention, but raw hegemony. Serbia withdrew, UN administration took over, detaching Kosovo. On February 17, 2008, with US-EU backing, Kosovo’s assembly unilaterally declared independence—sans Serbian nod, UN resolution, or clear international law. Over 50 nations, led by the West, recognized it promptly; China, Russia, India, Spain, and Greece rejected it, sparking legitimacy debates.

China’s Unwavering Stance on Kosovo Independence

China’s refusal to recognize Kosovo independence isn’t whimsy—it’s rooted in three ironclad principles, safeguarding core interests.

Territorial integrity is China’s non-negotiable red line, scarred by “century of humiliation” with Hong Kong and Macau ceded, Taiwan unresolved. Kosovo’s unilateral split mirrors Taiwan: a region breaking away with foreign backing, cloaked in “self-determination” to mask secession. Acknowledging Kosovo would arm critics: “If Kosovo can go, why not Taiwan via referendum?” Beijing sees this as a slippery slope trap.

Post-2008 declaration, Taiwan “recognized” Kosovo to court ties—China’s Foreign Ministry shot back: Taiwan lacks standing as it’s inherently Chinese. This underscores Kosovo as a proxy for “secession vs. unity.” Non-recognition builds a firewall around Taiwan.

Legally, Kosovo independence lacks foundation. UN Resolution 1244 (1999) affirms Kosovo as Serbia’s territory, mandating negotiated final status. Kosovo sidestepped talks, breaching this. The International Court of Justice’s 2010 advisory opinion deemed the declaration non-violative of international law but stopped short of statehood endorsement or precedent-setting. China argues self-determination fits decolonization (e.g., Algeria from France), not internal separations like Kosovo, which smacks of separatism.

As Beijing repeatedly states: “We respect Serbia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.” China-Serbia bonds are battle-tested: Cold War “alternative allies” in socialism; post-1999 bombing, Serbia vocally backed China; today, via Belt and Road, China funds Serbian high-speed rail, steel, and renewables, deepening ties.

Strategically, Serbia’s non-NATO status and Russian links make it China’s European foothold against US-NATO expansion. Kosovo, meanwhile, hosts Bondsteel—the US’s largest overseas base in the Balkans—making recognition tantamount to endorsing American military entrenchment, clashing with China’s geopolitical aims.

In 2025, China’s position on Kosovo independence holds firm: no diplomatic ties, prioritizing stability and sovereignty amid global flux. The saga endures—a millennium grudge meets modern power plays.

References

- 《科索沃独立的历史过程及其后果》 by Kong Hanbing

- Wikipedia: International Recognition of Kosovo

- ChinaMed: Beijing on the Kosovo Question

- ECFR: Kosovo

- Wikipedia: China–Kosovo Relations