In 1949, as New China emerged, Beijing (then Beiping) triumphed over 10 rival cities—including Harbin, Yan’an, Kaifeng, Luoyang, Xi’an, Nanjing, Shanghai, Chengdu, Chongqing, and Guangzhou—to become the capital. Each contender boasted strengths: Harbin’s industry, Yan’an’s revolutionary legacy, Nanjing’s political history, and Xi’an’s ancient heritage. Yet, Beijing’s strategic location, cultural depth, and proximity to the Soviet Union sealed its fate. Covering 1.66 million square kilometers in strategic value (including Xinjiang considerations), Chairman Mao’s choice reflected far-sighted vision. Explore why Beijing outshone rivals and its lasting impact.

Rivals: 11 Cities’ Strengths and Flaws

The selection process weighed 11 cities. Harbin offered strong industry but extreme cold (-20°C winters). Guangzhou excelled in southern economy but was too remote for northern integration. Shanghai and Guangzhou, as coastal hubs, risked naval attacks amid 1949 tensions.

Historical capitals like Xi’an (13 dynasties), Kaifeng, and Luoyang boasted cultural prestige but lagged in economy and population. Nanjing, the Nationalist capital, carried “short-lived dynasty” superstitions and Soviet distance issues. Chongqing and Chengdu’s basin geography hindered national expansion.

Yan’an symbolized revolution but lacked development. Beijing, a Yuan-Ming-Qing capital, balanced history, economy, and security.

Mao’s Choice: Beijing vs. Xi’an

The final contest pitted Beijing against Xi’an. Xi’an’s central location promised balanced growth, but Beijing’s advantages prevailed: near the Soviet Union for alliances, safer from sea threats, and preserved intact post-peaceful liberation—saving reconstruction costs for New China.

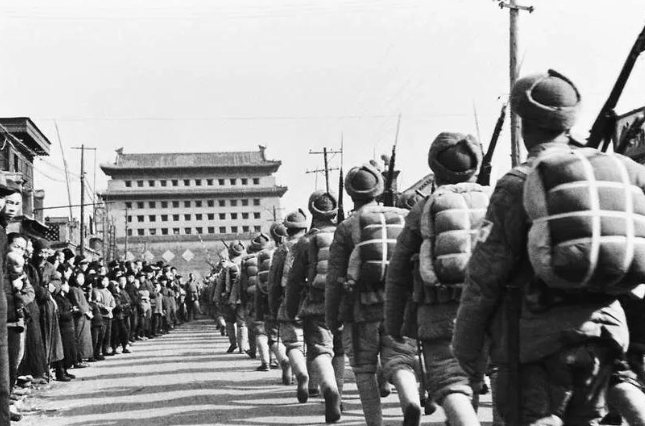

Beijing’s cultural icons (Forbidden Palace, Temple of Heaven) survived wars, offering symbolic continuity. Its “throat” position linked Northeast and interior, vital for defense. Mao’s vision: Beijing unified the nation, rejecting Nanjing’s capitalist ties for socialist ideals.

Strategic and Cultural Factors

Beijing’s location near the Bohai Sea and mountains ensured defense, while proximity to Liaoning and Shandong enhanced security. Psychologically, it resonated with people as an imperial capital, fostering acceptance.

Rejecting Nanjing symbolized a break from the old regime. Beijing’s ethnic fusion history supported New China’s unity. Ultimately, on October 1, 1949, Mao proclaimed the PRC from Tiananmen, renaming Beiping to Beijing.

Conclusion

Beijing’s 1949 selection as capital, defeating 10 rivals, stemmed from Mao’s strategic foresight—balancing security, culture, and alliances. Today, as it hosts the 2025 Victory Day parade, Beijing embodies China’s rise. Explore this pivotal decision’s legacy!