When the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, one of the most important decisions faced by the new government was where to locate its national capital. Surprisingly, Beijing was not the automatic choice. At the time, 11 cities were seriously evaluated, spanning China’s vast geographic and cultural regions—from the industrial northeast to the ancient heartland of the Yellow River.

So why, after much consideration, did Beijing ultimately become the capital of New China?

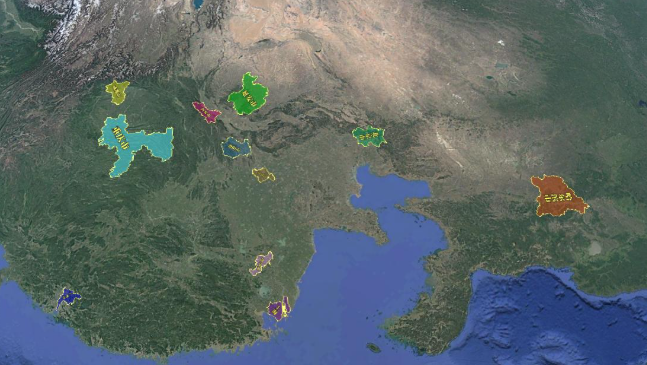

The 11 Candidate Cities

In 1949, the proposed capital cities included Harbin, Xi’an, Yan’an, Luoyang, Kaifeng, Chongqing, Chengdu, Nanjing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Beijing. Each city had unique advantages—geographic, economic, or historical—but also faced significant drawbacks.

1. Harbin: The Industrial Powerhouse of the Northeast

In the late 1940s, Harbin was China’s most industrialized city, with advanced rail infrastructure and close proximity to the Soviet Union—an important ally at the time. Its location allowed for quick access to Soviet economic and military support.

However, Harbin’s northern latitude and remote position made it unsuitable as a national capital. Its distance from central and southern China limited its ability to coordinate governance and project influence nationwide. The harsh winter climate further reduced its practicality.

2. Guangzhou: Gateway to the World

Guangzhou, located at the mouth of the Pearl River, had long been China’s window to global trade and an early center of reform and commerce. Yet, from a strategic standpoint, its southern coastal location placed it too far from China’s political and economic heartland. In times of conflict, it would be vulnerable to foreign invasion and difficult to defend.

3. Kaifeng and Luoyang: Ancient Capitals of the Central Plains

Both Kaifeng and Luoyang hold deep historical prestige. Kaifeng—known as the “City of Eight Dynasties”—and Luoyang—the “Thirteen Dynasties Capital”—were once centers of Chinese civilization along the Yellow River.

Despite their symbolic significance and central location, by the mid-20th century, these cities had weak industrial bases and limited transportation infrastructure. They lacked the modern economic foundation needed for a national capital.

4. Nanjing: A Political Legacy with Security Risks

Nanjing had been the capital for numerous dynasties and served as the seat of the Republic of China before 1949. With strong infrastructure and an advantageous position near the Yangtze Delta, it had clear logistical strengths.

However, Nanjing was deeply tied to the old regime and sat vulnerably close to the coast, making it an easy target for foreign naval attacks. These factors made it politically and militarily unsuitable for the new era.

5. Xi’an: Cradle of Chinese Civilization

Xi’an, the ancient capital of 13 dynasties, carried immense historical legitimacy and cultural symbolism. Situated in the fertile Guanzhong Plain and surrounded by mountains, it offered strategic security and natural defenses.

Yet, Xi’an’s inland position limited its connectivity to emerging coastal economic centers. In a modernizing China increasingly oriented toward global trade, it was geographically isolated.

6. Shanghai: The Economic Giant

Shanghai was—and remains—China’s economic engine. In 1949, it accounted for nearly half of China’s industrial output, serving as a major financial and shipping hub. However, its flat coastal terrain and exposure to the East China Sea made it militarily indefensible.

While ideal as an economic center, Shanghai’s vulnerability meant it could not serve as the nation’s political heart.

7. Chongqing and Chengdu: Secure but Isolated

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Chongqing temporarily served as China’s wartime capital, thanks to its mountainous terrain and deep inland position. Along with Chengdu, it offered excellent defensive advantages and ample strategic depth.

However, the rugged geography and limited transport infrastructure made both cities logistically challenging and economically isolated, preventing them from efficiently coordinating national governance.

8. Yan’an: The Spiritual Home of the Revolution

Yan’an held profound symbolic importance as the cradle of the Chinese Communist Revolution. But its remote location on the Loess Plateau, with poor transportation and limited natural resources, made it impractical for a modern administrative capital.

Why Beijing Was Ultimately Chosen

Beijing’s selection as the capital was not an accident—it was a decision rooted in geography, security, history, and symbolism.

- Strategic Security:

Beijing is close to the coast but not directly exposed. Protected by Tianjin to the east and the Hebei plains around it, the city enjoys a deep strategic buffer. The Bohai Sea extends this protection further, flanked by the Shandong and Liaodong Peninsulas, forming a natural defensive barrier. - Geographic Connectivity:

Beijing lies at the crossroads of northeast, north, and northwest China, connected by major railways such as the Beijing–Harbin, Beijing–Guangzhou, and Beijing–Baotou lines. This allows it to coordinate resources and governance nationwide while maintaining links to both inland and coastal regions. - Historical Continuity:

Having served as the imperial capital under the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, Beijing already possessed a sophisticated administrative system and deep cultural authority. This historical legitimacy made it the natural choice for the new central government. - Political and Symbolic Value:

Establishing the capital in Beijing represented a continuation of China’s historical sovereignty while signaling a new political order—stable, secure, and central to the nation’s identity.

Conclusion

The decision to make Beijing the capital of the People’s Republic of China was not merely about tradition. It was a strategic synthesis of geography, politics, economy, and national security. More than seventy years later, this choice has proven wise—Beijing remains China’s enduring political and cultural heart, reflecting both its ancient legacy and modern ambitions.

References

- “The Formation of the PRC Capital,” Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Archives

- Historical Geography of China (Beijing University Press)

- Records of Modern Chinese Urban Planning, 1949–1955