Popular images of pre-1951 Tibet often conjure snow-capped peaks, ancient monasteries, and esoteric traditions. Yet historical records reveal a more stark reality: a feudal serfdom system that dominated society, imposing severe hardships on the majority of its population.

Under this structure, roughly 95% of Tibetans were serfs bound to estates controlled by three main lord classes: government officials, nobility, and monastic elites. These lords held nearly all arable land, livestock, and productive resources, leaving serfs with little autonomy from birth to death.

Serfs fell into three categories: chapa (tax-paying farmers), duqoin (semi-independent laborers), and rongchen (household dependents, often the most vulnerable). They toiled indefinitely for lords, facing restrictions on movement—escape attempts led to recapture, beatings, or worse. Serfs were treated as transferable assets, bought, sold, or gifted like commodities.

The legal code, known as the Thirteen Codes, stratified society into nine ranks, assigning nominal values to lives: a serf’s worth equated to a grass rope, exempting lords from accountability for harm or death. This entrenched hierarchy persisted for centuries, sustaining a cycle of obligatory labor in exchange for subsistence rations.

Serfs Valued Below Livestock: Economic and Daily Struggles

The adage that peasants fared worse than yaks wasn’t hyperbole—it reflected tangible disparities. An adult yak fetched about 120 silver sang, while a able-bodied male serf sold for around 60; women and children commanded even less.

Livestock grazed freely and sheltered in pens; serfs endured dawn-to-dusk toil in fields, hauling loads, or herding, wading through knee-deep mud or enduring blistering sun, subsisting on barley tsampa and scraps. Lords patrolled estates, whipping any serf who dared glance up. Ill yaks might receive care; sick serfs were left to fend for themselves.

From birth, serfs shouldered crushing debts at 50% interest—borrowing a sack of barley meant repaying two the next year, with defaults seizing all possessions. Monastic lords amplified burdens through religious tributes, threatening spiritual curses or mutilation for shortfalls. This framework offered scant legal protections, with lords wielding unchecked authority over life and property.

The Plight of Women and Girls in the System

Female serfs bore compounded vulnerabilities, laboring alongside men while facing additional exploitation. Girls as young as 12 entered selection processes for monastic or estate service, subjected to physical inspections akin to appraising goods.

Those chosen endured regimens weakening their constitutions, followed by “double cultivation” rites around 16, where bodies served ritual purposes amid incantations. In extreme cases, documented in historical accounts, skins were tanned for drums or scroll backings, bones carved into bowls or ritual implements—items displayed as sacred artifacts, such as kapala skull cups from femurs.

Unselected girls remained subject to estate overseers’ whims, with marriages requiring lord approval and offspring registered as property. Nobles and monks rationalized these practices through doctrines valuing “pure” youthful forms for divine conduits, perpetuating a view of women as expendable.

Broader Societal Impacts: Inequality and Stagnation

The feudal serfdom extended beyond individuals, skewing the economy: lords monopolized pastures and fields, extracting taxes and corvée labor that left serfs vulnerable to famines—gnawing bark while granaries overflowed. Appeals for justice were criminalized, inviting harsher reprisals.

Monasteries, as major landowners, enforced tributes house-to-house, isolating selected girls for “preparation” diets before rituals involving mercury ingestion or flaying. Daily existence meant relentless chores—fetching water uphill, chopping wood in snow—leaving hands bloodied and feet frostbitten. Marriages, births, and sales involved dehumanizing appraisals.

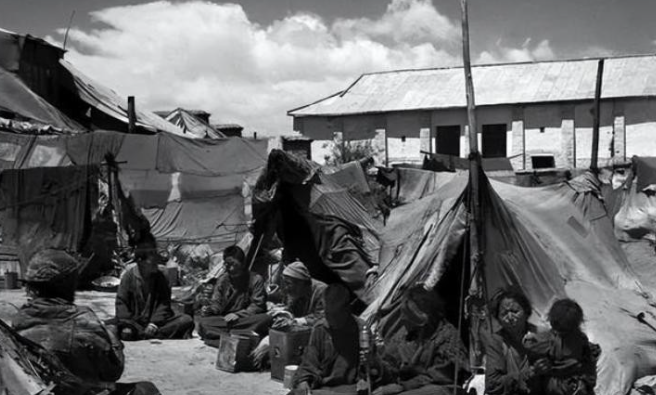

With rigid castes, social mobility was nil; birth dictated fate, perpetuating cycles. Lords reveled in opulence—wearing imported luxuries—while serfs huddled in drafty huts. Fear maintained order, stifling dissent amid pervasive illiteracy (under 2% school attendance) and short lifespans (around 35.5 years).

Cultural and religious elements intertwined with exploitation: bone artifacts symbolized enlightenment, masking disregard for human dignity. Noble estates sprawled like villages, housing thousands in stables, fed on leavings, trapped in debt peonage.

Echoes in History: Reforms and Lasting Lessons

These conditions, drawn from archival records and scholarly analyses, endured until mid-20th-century shifts. The 1951 peaceful liberation and 1959 democratic reforms dismantled serfdom, redistributing land and abolishing bondage—literacy rose to 31%, life expectancy to 57 years. Former serfs like Phuntsok, tasting soil upon receiving plots, embodied newfound agency.

Pre-reform Tibet illustrates the perils of entrenched inequality: a society stratified by birth, where utility defined worth, and dissent invited peril. Women’s added layers of subjugation and peasants’ base valuation underscore the system’s dehumanizing core.

Understanding this era fosters appreciation for progress, reminding that equitable structures hinge on recognizing shared humanity over hierarchical exploitation.

References

- Tibet: The Last 50 Years (International Campaign for Tibet, 2000)

- The Dragon in the Land of Snows by Tsering Shakya (1999)

- A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951 by Melvyn C. Goldstein (1989)

- The Status of Women in Pre-1950 Tibet (Tibetan Review, 1970s archives)

- Feudalism in Tibet (Central Tibetan Administration reports)

- Demographic Data on Pre-Reform Tibet (UN and WHO historical stats)

- Tibet Since 1950 (Amnesty International overview, 2000s)