On September 17, the Financial Times reported that China’s internet regulator had issued directives to several top domestic tech firms, ordering them to immediately stop purchasing Nvidia’s AI chips. Even signed contracts must now be canceled.

Just two days earlier, China’s State Administration for Market Regulation had launched an antitrust investigation into Nvidia. The timing suggests these two moves were anything but coincidental.

To understand this sequence of actions, we need to rewind a bit.

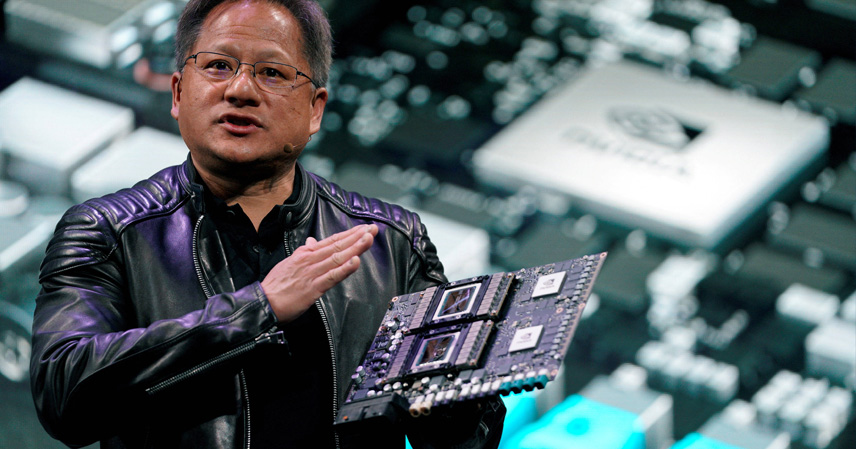

Over the past few years, the United States has tightened export restrictions on China’s high-tech industries, especially in semiconductors. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Commerce explicitly banned exports of top-tier AI chips—such as Nvidia’s A100 and H100—to China.

These chips function like the “brains” of AI training. Without them, large-scale model development becomes severely constrained.

Faced with this, Nvidia complied with U.S. controls by halting sales of its original high-performance products to China. Instead, it rolled out “downgraded” versions tailored for the Chinese market—such as the A800, H800, and more recently, the H20.

These “special editions” were deliberately cut down in performance to just below U.S. regulatory thresholds, yet their prices remained higher than many buyers expected.

For domestic firms desperate for computing power, it was like buying water in a desert—lower quality, higher cost, and with no guarantee of stable supply.

Even worse, Nvidia failed to deliver these substitute products reliably. Many Chinese companies that placed orders faced repeated delays, sometimes with no clear delivery dates at all.

Concerns also grew over potential security risks. These AI chips are installed in data centers and key servers, housing sensitive algorithms and data. If hidden backdoors existed, the consequences would be catastrophic.

History already provides cautionary tales—from the PRISM surveillance scandal to intelligence leaks—showing how U.S. tech dominance has been leveraged for information gathering. Trust in American hardware has been steadily eroding worldwide.

This raises a critical question: Can such an unequal tech-supply relationship be sustainable?

China’s latest antitrust probe and suspension of Nvidia purchases are not merely commercial moves; they represent a direct response to this imbalance.

The U.S. has weaponized supply chains against Chinese companies while still hoping its firms can profit from China’s vast market. This logic is fundamentally unsustainable.

No surprise then that following China’s decision, U.S. Treasury Secretary Bessent quickly voiced dissatisfaction, calling the timing of China’s probe “inappropriate.” Yet this criticism rings hollow, given that just days earlier Washington had added 23 Chinese entities—many tied to semiconductors—to its export blacklist.

But if China stops importing Nvidia AI chips, what’s next for its tech industry?

The most immediate path is boosting domestic alternatives. Huawei’s Ascend series has made significant strides, with the Ascend 910B already deployed in cloud platforms and enterprise computing centers.

Cambricon’s Siyuan series has entered commercial use, while startups like Biren Technology and Moore Threads are rapidly narrowing the gap with leading products.

Although these chips don’t yet rival Nvidia’s H100 or H200 in peak performance or ecosystem maturity, they are already viable substitutes in specific use cases.

Non-U.S. alternatives also exist. Some European and UK AI chipmakers—though smaller in scale—are developing products suitable for niche applications. Still, challenges in capacity and compatibility mean they cannot yet serve as large-scale replacements.

In the longer run, innovation may provide a breakthrough. Dedicated AI chips (ASICs) for specialized tasks, or RISC-V–based accelerators, are already being pursued by Chinese research teams.

The ripple effects on Nvidia—and the broader U.S.-China AI dynamic—could be profound. Nvidia’s market cap recently topped $1 trillion, largely fueled by AI chip demand. China accounts for about 20% of its revenue. Losing access to this market would deal a heavy blow, both financially and in terms of ecosystem development.

China’s vibrant AI sector also provides critical feedback for technological iteration. Without this partnership, Nvidia risks falling behind in global innovation.

Ironically, Washington’s restrictions may accelerate China’s self-reliance. Domestic chipmakers, bolstered by policy and market demand, could break Nvidia’s dominance sooner than expected. This could lead to two distinct, parallel ecosystems competing in different domains.

Challenges remain. World-class GPUs are more than hardware—they depend on mature software ecosystems. Nvidia’s CUDA platform remains a formidable barrier. But this gap is not insurmountable. Huawei’s CANN and Cambricon’s developer tools are steadily building ecosystems of their own.

With consistent R&D investment and an open approach to ecosystem building, achieving parity in key areas within three to five years is plausible.

Seen this way, China’s “ban” may be less a setback than a catalyst. Painful in the short term, it could ultimately accelerate domestic solutions and strengthen the entire industry chain.

The U.S. is unlikely to relax restrictions, viewing advanced chips as strategic assets. But China, fully aware of the risks of dependence, is determined to push forward.

In the coming years, expect heavier investments, stronger policy support, and end-to-end ecosystem development in China’s semiconductor and AI sectors. When domestic chips reach competitive levels in performance, cost, and supply reliability, Nvidia—and others with monopolistic tendencies—will feel the pressure.

China has crossed similar turning points in other technology fields. The chip industry will be no exception. This Nvidia episode may well be remembered as a milestone on the road to self-sufficient computing power.

In short, China’s market is not an easy profit pool. Cooperation is welcome—but only if it’s mutual and fair.

Whether Nvidia’s retreat is imposed or self-inflicted is up for debate. But one thing is certain: the era of China being perpetually constrained by others in critical technologies must come to an end.

Yes, the road may involve short-term pain—but someone must take this step forward. Should China continue relying on foreign chips, or seize this chance to walk its own path?

References

- Financial Times, September 17, 2025

- U.S. Department of Commerce export control updates (2022–2025)