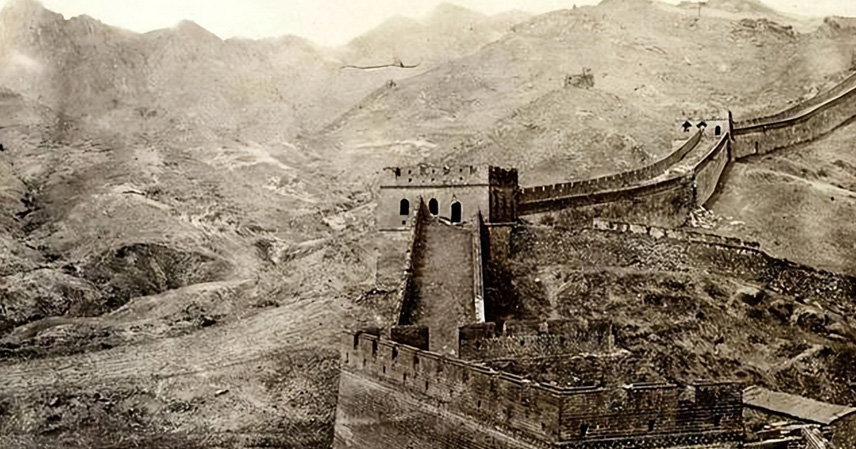

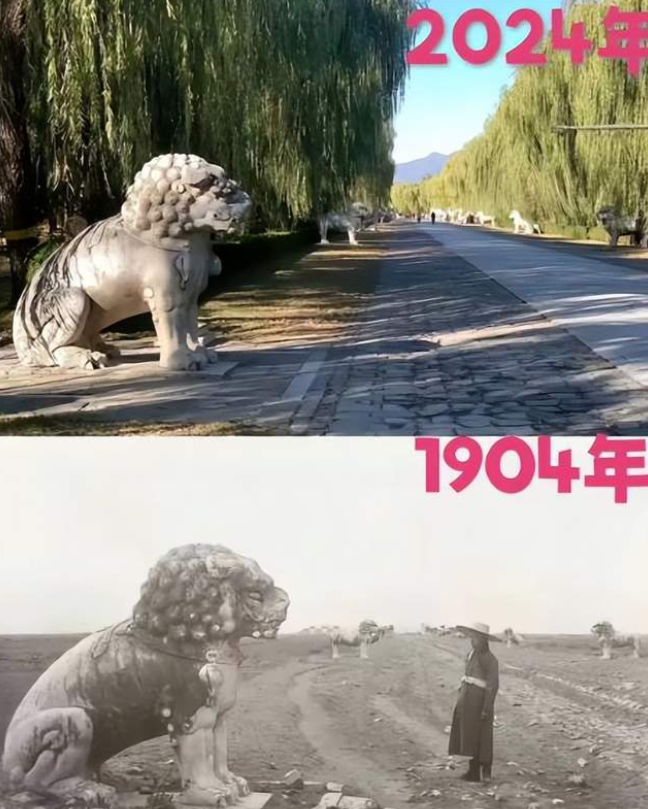

When you imagine ancient times, do you picture lush green forests, clear waters, and idyllic mountains? Unfortunately, that’s only a beautiful illusion. If you could travel back in time, the reality would shock you: around population centers, the hills were barren. Old photographs from the late Qing dynasty, from Beijing to Xi’an, from the Great Wall to the Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum, show nothing but desolate yellow earth. So where did all the trees go?

The answer is simple yet brutal: they were consumed by our ancestors as survival necessities. It wasn’t because ancient people lacked environmental awareness, but because they had no choice. Without oil, natural gas, or affordable coal, forests became their most accessible “ATM.”

Forests as the Foundation of Survival

In ancient China, life was a constant struggle against nature. Forests weren’t just part of the ecosystem—they were the single most critical resource. Today we use electricity and natural gas, but back then, everything relied on wood: cooking, heating in winter, building houses, ships, furniture, and tools. As populations grew and cities expanded, demand for timber reached astronomical levels.

Take Tang-era Chang’an, for example. As the world’s largest city at the time, it consumed over 400,000 tons of timber annually. Although located near the resource-rich Qinling Mountains, even those reserves were quickly depleted. Tang writer Liu Zongyuan lamented in his works that “beams and pillars were scarce in the southern mountains.” Records show that timber had to be transported from Shanxi (545 km away) and Inner Mongolia (670 km away)—not because people preferred distant sources, but because there were simply no nearby trees left to cut.

Beijing’s story was no different. During the Yuan dynasty, building the White Pagoda Temple alone required 4,000 soldiers to fell 58,600 trees. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, the capital expanded further. With over 100,000 courtyard houses built, construction consumed an estimated 24 million large trees. By the late Qing, Beijing’s Western Hills retained only a few hundred hectares of forest out of 10,000, leaving a forest cover rate of just 1.3%—explaining the barren landscapes captured in old photographs.

Why Not Use Coal Instead?

You might wonder: wasn’t coal already available in ancient China? The truth is yes—China discovered coal as early as the Warring States period, calling it “stone charcoal.” But it never became a widespread household energy source.

There were three major reasons:

- Primitive mining technology, high risk, high cost

Ancient mining relied heavily on manual digging, making it slow, dangerous, and costly. Gas explosions, cave-ins, and suffocation were common. Compared to simply chopping wood, coal mining was prohibitively expensive. - Transport challenges

Coal is heavy. In the pre-railroad era, long-distance transport was extremely costly. Unlike timber, which could float down rivers, coal had to be hauled by ox- or horse-drawn carts. Yuan dynasty records noted that coal had to be carted from the Western Hills to Beijing—a massive logistical burden. - Primarily industrial, not domestic

Coal’s high heat value made it ideal for industries like iron smelting, porcelain firing, and salt production, especially from the Song dynasty onward. While this eased some pressure on forests, coal never fully replaced wood as a household fuel. In cities like Beijing, coal only became common when nearby forests were exhausted and firewood prices soared. Even then, the poor often burned coal dust mixed with soil, formed into cheap briquettes.

No Hunting or Fishing During Famines

Another question arises: if forests were gone, why didn’t people hunt or fish during famines?

The harsh truth is that by the time famine struck, all available wild animals had long been hunted to extinction by desperate populations. Famine unfolded gradually, and by the time most people realized they were starving, no wild game remained—only tree bark and clay to eat.

Moreover, hunting and fishing required both skill and physical strength. In the weakened, starving state of famine victims, such survival tactics were impossible. Even if someone managed to catch a small animal, the energy expended would outweigh the calories gained. Environmental destruction didn’t just strip the land of resources—it severed humanity’s last fallback options.

Lessons from History: Technology as Salvation

In short, much of Chinese history could be seen as a history of deforestation. As forests disappeared, ecological disasters multiplied. When Beijing’s Western Hills were stripped bare, water retention collapsed, leading to frequent floods. During the Qing dynasty, floods struck 129 times in 268 years, averaging once every two years. On the Loess Plateau, deforestation caused massive soil erosion, worsening Yellow River floods: from 56.4 floods per century in Tang-Song times to a staggering 137.3 floods per century under the Ming and Qing.

This vicious cycle was not unique to China. Globally, 1.8 billion hectares of forest vanished over the last 5,000 years. Contrary to the stereotype that technology accelerates destruction, in terms of forests, industrialization actually brought salvation. The Industrial Revolution introduced new fuels and materials, reducing reliance on wood. With more efficient agriculture, humans could feed larger populations and finally afford to care about nature.

Since the 20th century, large-scale reforestation efforts in both Europe and China have reversed centuries of damage. After 1949, China mobilized soldiers, students, and citizens for tree planting campaigns. The once-barren Western Hills of Beijing became forest parks, while the Loess Plateau gradually turned green again. Forest coverage in China rose from 8.6% in 1949 to 25% today.

Meanwhile, large-scale deforestation still plagues poorer regions. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization notes that in Africa, 80% of felled trees are used as firewood, showing that only after solving basic survival needs can societies begin to truly pursue environmental harmony.

References

- Yuan Dynasty 《析津志》 records on coal transportation.

- Liu Zongyuan’s writings on Qinling deforestation.

- UN FAO reports on global deforestation and firewood usage.

- Historical flood data of the Yellow River across Tang-Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties.