How Historical Dramas Shape Our Perception

Many modern audiences love watching Chinese historical dramas, which offer a glimpse into ancient customs, court life, and traditional attire. Popular shows like Palace (starring Yang Mi and Feng Shaofeng) have captivated viewers with their depictions of the Qing Dynasty, China’s last imperial era.

However, these dramas often misrepresent the Qing hairstyle. On screen, men are typically shown with the front half of their heads shaved and a long braid hanging down the back — a style often called the “yin-yang head.” But was that really how Qing men looked in history? The truth may surprise you.

Hair as a Cultural Marker in Chinese History

Throughout China’s 5,000-year civilization, hairstyles have reflected social norms, regional differences, and political power. From the rituals of dining and dress to how people wore their hair, every dynasty expressed its own cultural identity.

During the Warring States period, for example, men from Qin tied their hair into high topknots at the center, while those from Chu placed their hair buns slightly to the right. These small variations symbolized regional identities and even political allegiances.

By the time of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), hairstyles had become a political statement as much as a cultural one.

The Origins of the “Queue” Hairstyle

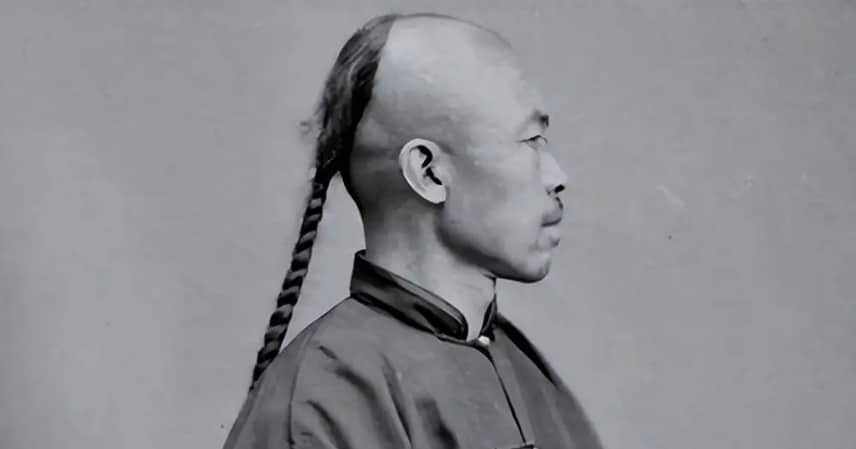

When the Manchu people conquered China and established the Qing Dynasty, they enforced a new hairstyle on Han Chinese men — shaving the front portion of the head and braiding the remaining hair into a long queue (or pigtail).

This wasn’t a random aesthetic choice. On the Manchu plains, men who hunted and rode horses found long hair impractical. To prevent hair from blowing into their eyes during battle or hunting, they shaved the front and left the back long enough to braid.

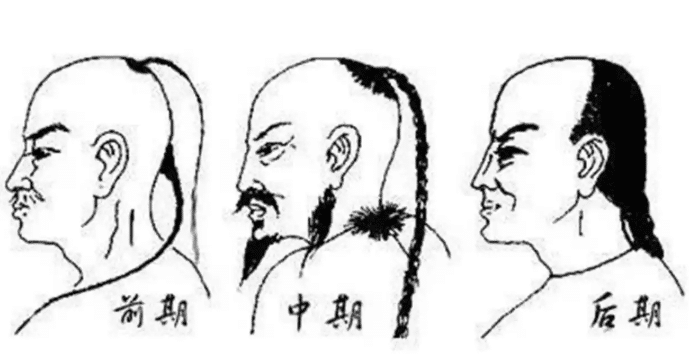

Early on, these braids were shorter and thinner, tied high near the crown — quite different from the long “yin-yang” style seen in later centuries. Only after the Manchu rulers sought to standardize appearance and impose loyalty did the queue become mandatory for all males under the slogan “Keep your hair and lose your head, or cut your hair and keep your head.”

The Evolution from “Mouse Tail” to “Ox Tail”

Initially, the queue was thin — sometimes referred to as a “mouse tail”. Over time, as both fashion and social order evolved, the braid became thicker and longer, earning the nickname “ox tail.”

By the mid-to-late Qing period, the style had become what we now call the yin-yang head — shaved front, long braid back — representing the empire’s distinct identity.

However, during the early Qing, not all men wore the hairstyle this way. The full “yin-yang” look we see in modern dramas only became common in the 18th and 19th centuries, after several rounds of cultural adaptation and imperial reform.

So while TV dramas often show every Qing man with a shiny forehead and a trailing braid, that’s a historical oversimplification.

Beyond Fashion: The Meaning of Hair

In traditional Chinese culture, the saying “Your body, hair, and skin are gifts from your parents” meant that cutting one’s hair was seen as disrespectful. This made the Manchu hairstyle decree deeply controversial among Han Chinese scholars and commoners alike.

Still, as the Qing rulers consolidated power, they used the hairstyle as a symbol of unity and control — a visible sign of allegiance to the new dynasty. The queue thus became not just a haircut, but a political tool that shaped how identity and loyalty were expressed.

What We Can Learn Today

Over time, the queue disappeared along with the Qing Empire itself, but it remains a fascinating example of how fashion, politics, and culture intertwine.

Today, we emphasize cultural diversity and historical accuracy. Understanding how such traditions evolved helps us see the complexity of China’s history, rather than accepting dramatized versions at face value.

So next time you watch a Qing drama, remember — not every man walked around with a perfect “yin-yang head.” The truth, as always, is more nuanced.

References

- Qing Dynasty archives on hair regulations (1645–1900).

- “The Queue Order and Cultural Integration,” Journal of East Asian History.

- The Great Qing: China in 1644–1911, by Evelyn S. Rawski.