In 1931, China was shaken by the Mukden Incident, also known as the September 18th Incident. At that time, the Japanese Kwantung Army had fewer than 20,000 troops, while the Chinese Northeast Army commanded by Zhang Xueliang had as many as 400,000 soldiers, with superior weapons and equipment.

Yet, despite this numerical and equipment advantage, the Northeast Army adopted a policy of non-resistance. Without fighting, they withdrew, allowing the Japanese to occupy Shenyang without firing a shot. Soon after, Japan seized the entire Northeast region.

As the commander of the Northeast Army, Zhang Xueliang became a scapegoat of history, condemned as a “national sinner” and denounced by millions.

However, in later interviews, Zhang strongly refuted these accusations, declaring:

“People curse me for not resisting during the Mukden Incident, but I absolutely disagree. I will not take that blame. I was not wrong.”

So, what was the truth behind Zhang’s order of “no resistance”?

The Mukden Incident and the Fall of the Northeast

On the night of September 18, 1931, around 10 p.m., a sudden explosion shattered the silence near Liutiaohu, 800 meters south of Shenyang’s Beidaying. Japanese soldiers secretly planted explosives on a section of the South Manchuria Railway and staged the scene with corpses dressed in Chinese uniforms.

Japan then falsely accused the Chinese army of sabotaging “Japanese property” and used this as a pretext to launch the Mukden Incident. That night, the Kwantung Army attacked the Northeast Army’s barracks. True to history, Zhang’s troops offered no resistance and abandoned Shenyang.

Within just four months, all of Manchuria fell into Japanese hands.

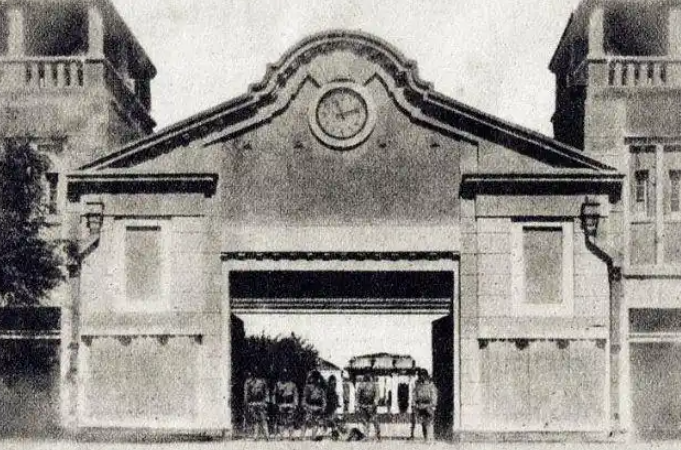

The loss was not only territorial but also strategic. The Northeast was China’s most advanced industrial base, home to the Shenyang Arsenal — once called the “largest arsenal in Asia.” At its peak, it employed 36,000 workers, produced 60,000 rifles and nearly 1,000 machine guns annually, along with artillery and ammunition.

But after the Japanese takeover, all of this — including 120,000 rifles, 4,000 machine guns, 3,000 cannons, and 200 aircraft — became spoils of war for Japan, greatly strengthening their military.

For decades, many have argued that if Zhang had resisted, Japan might have been forced into a costly battle, which could have slowed their invasion. Instead, Zhang ordered his soldiers to store their weapons and retreat, reinforcing the image of Chinese weakness.

This decision placed Zhang Xueliang on history’s “pillar of shame.”

Zhang Xueliang Explains the Decision

Many historians and the public believe there were two main reasons:

1、Chiang Kai-shek’s Policy:

Before 1937, Chiang advocated “internal pacification before external resistance.” His priority was defeating the Communists rather than fighting Japan. Thus, many assumed Chiang ordered Zhang not to resist.

- Zhang’s Self-Preservation:

As the son of Zhang Zuolin, the “Warlord of Manchuria,” Zhang had inherited power in the Northeast. Direct conflict with Japan could weaken his forces, leaving him vulnerable to rival warlords.

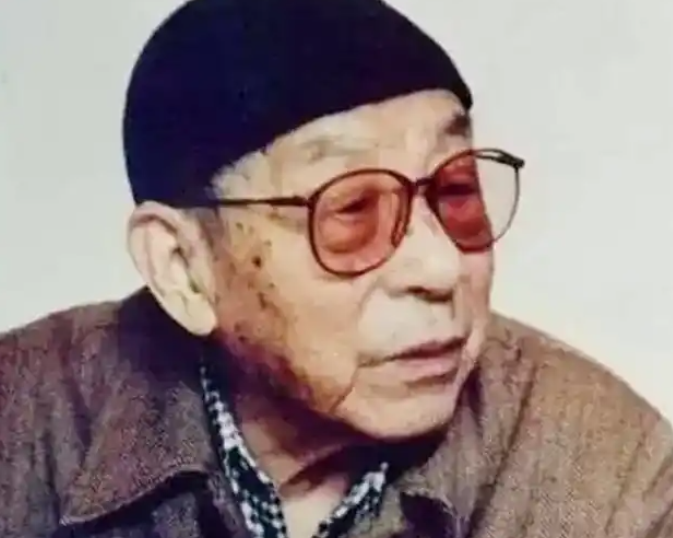

But in a 1991 interview, Zhang denied both explanations. He insisted:

“The decision had nothing to do with Chiang. It was made by us in the Northeast Army. People blame me for not resisting, but I was not wrong.”

According to Zhang, he was in Beijing recovering from illness at the time. When the Mukden Incident erupted, he assumed Japan would not fully invade, as such actions would bring severe consequences for themselves. He compared it to previous provocations like the Nakamura and Wanbaoshan incidents, which he believed were meant to stir trouble rather than launch a full-scale war.

Thus, Zhang misjudged the situation, ordering restraint to avoid giving Japan a justification for escalation. He later admitted this was a grave error.

Zhang’s Later Reflections: A Misjudgment, Not Betrayal

When Japan launched its full invasion, Zhang realized too late that he had been wrong. With Shenyang fallen and the arsenal captured, his army was left powerless.

He explained:

“It was not that we refused to resist. It was that I misjudged the situation.”

While critics accused him of cowardice, Zhang argued that he never intended to surrender. As proof, decades later he risked everything in the Xi’an Incident (1936), detaining Chiang Kai-shek to force a united front against Japan. For this, he endured 52 years of house arrest.

Still, Zhang carried deep regret. On his 90th birthday, he admitted:

“I am a sinner, the chief among sinners. If I had known Japan would act that way, I would have fought to the death.”

Yet history allows no “ifs.” The non-resistance of 1931 directly enabled Japan’s occupation of Manchuria and became one of modern China’s greatest tragedies.