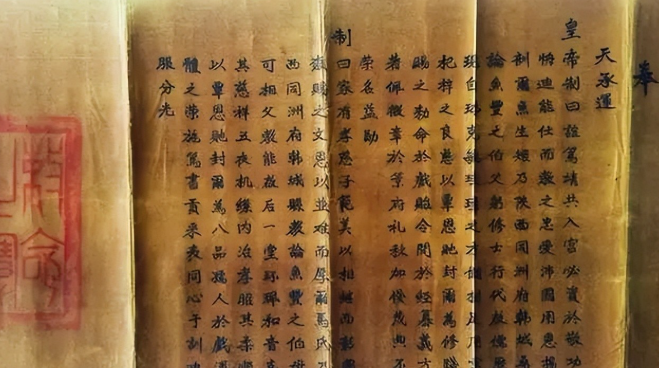

What devastation can a mere letter unleash? In early 1794, as the Macartney Embassy departed Guangzhou harbor with Emperor Qianlong’s response in hand, few could foresee that these scant pages would ignite a chain of events reshaping two empires. Comprising just 976 Chinese characters, the missive brimmed with the Qing court’s self-assured superiority and profound detachment from global shifts.

Today, this artifact rests silently in a display case at the British Museum, serving as a stark reminder: When an empire turns a blind eye to the world, what fate awaits?

Echoes of the Industrial Revolution Unheard in the Forbidden City

By 1772—the 37th year of Qianlong’s reign—Britain across the seas was undergoing seismic transformation. Steam engines thrummed in factories, textile looms whirred at unprecedented speeds, and coal mines echoed with extraction’s clamor. Britons harnessed machines to eclipse human labor, multiplying productivity and propelling the nation into a frenzy of innovation.

The Industrial Revolution didn’t just swell coffers; it revolutionized mindsets. Merchants scoured the globe for markets and raw materials, their ambitions propelled by steamships to every corner of the earth.

Yet in Beijing, Qianlong remained oblivious. Absorbed in compiling the Siku Quanshu encyclopedia, he basked in the illusion of a pinnacle era. To him, the Qing realm was vast and bountiful, its tributaries dutiful—why entangle with distant “barbarians”? Daily rhythms in the Forbidden City persisted: morning audiences, memorials, garden strolls, poetry—unchanged.

Unbeknownst to him, as verses lauded imperial glory, the world reordered itself. Western vessels, once wind-dependent, now steamed at will, bridging oceans effortlessly. This chasm in awareness foreshadowed a cataclysmic clash between a nostalgic old power and a surging newcomer.

An Embassy Brimming with Optimism Sets Sail

King George III, ever astute, grasped China’s market allure: a populace of hundreds of millions. Britons craved Chinese tea, porcelain, and silk—essentials for the elite. Yet trade teetered on imbalance; silver flowed eastward, with little in return that tempted the Chinese.

To forge ties, George dispatched a formal delegation in 1792. Preparations were lavish: gifts included telescopes revealing lunar craters, globes mapping five continents, self-winding clocks, and a steam engine model—emblems of British ingenuity.

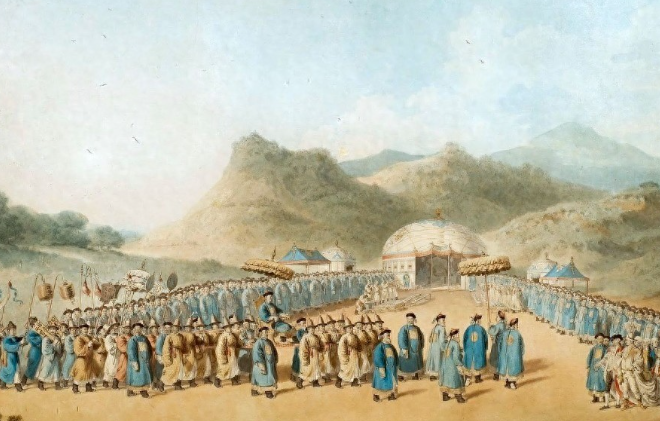

Lord Macartney, the seasoned envoy, was tasked with securing diplomatic ties, a Beijing legation, more ports, and perhaps a trading enclave. In 1793, the flotilla—dozens of vessels, over 700 souls, laden with treasures—sailed from Portsmouth, enduring a year’s voyage across tempests.

Aboard, Macartney pondered Qing etiquette, even brushing up on Mandarin, envisioning a bridge to modern relations. Arriving at Tianjin amid Qianlong’s 80th birthday festivities, the timing seemed providential.

To Kowtow or Not: The Ritual Standoff

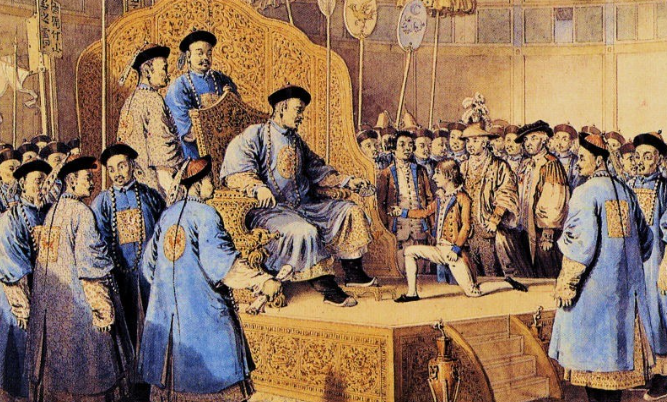

Trouble brewed before entering the capital. Qing officials insisted on the full kowtow: three kneelings, nine prostrations—a ritual for subjects greeting the sovereign.

Macartney balked. Representing a peer monarch, he deemed it humiliating. European protocol favored bows or single-knee genuflections; foreheads to the floor? Unthinkable.

Qing envoys held firm: Ancestral custom brooked no exceptions, not even for the British king. Days of deadlock ensued. Andon, the wily courtier, proposed a compromise: British rites before Qianlong’s portrait, full obeisance to the man.

Macartney refused. With celebrations looming, he relented to a single knee—a knightly salute—allowing both sides to save face. Officials acquiesced tacitly, but the rift cast a pall, exposing irreconcilable worldviews.

Gifts of Wonder Ignored by the Emperor

At the birthday banquet, Britons unveiled their marvels, hoping to awe with Industrial Revolution prowess. Telescopes pierced distant stars, globes delineated oceans and lands, clocks ticked via intricate gears, and the steam model promised boundless power—humanity’s triumphs crystallized.

Qianlong’s response stunned them. A cursory glance, a wave to pack it away. Politely deeming them “ingenious,” he inwardly dismissed: Mere curiosities. The Qing lacked for nothing; the Imperial Observatory had its scopes, palaces brimmed with maps. The steaming contraption? Ominous and inutile.

Rooted in Confucian priorities—poetry, arts over mechanics—the emperor viewed gadgets as trifles, not harbingers of productivity leaps. To him, the Qing was consummate; emulation unnecessary. Hopes dashed, gifts consigned to storage unseen, Macartney sensed the mission’s faltering.

976 Characters That Sealed a Dynasty’s Fate

The coup de grâce came September 1793: Qianlong decreed the embassy’s departure post-festivities. Requests for relations, ports, and bases? All rebuffed. A reply to George would suffice.

Penned swiftly in 976 characters, the edict oozed condescension. It opened graciously: Britain’s distant homage to celestial virtue was noted. Yet requests crumbled: “Our realm yields abundance; we need no foreign wares for exchange.” Resident envoys? Forbidden by tradition. More ports? Guangzhou sufficed; excess bred chaos.

Laced with phrases like “celestial sway extends afar” and “myriad realms pay tribute,” it equated Britain to tributaries like Korea— a peripheral isle unworthy of parity. Qianlong overlooked the island’s industrial might.

In January 1794, Macartney sailed homeward, poring over the letter in dismay. His report home decried the Qing as a “rotting hulk,” vulnerable to the slightest shove.

The Butterfly Effect of Dismissal

The letter rippled across Europe upon arrival. Diplomats pored over translations, deriding Qing myopia, spotting vulnerabilities. Merchants pivoted: With fair trade barred, opium surged—profitable, despite ethics—to balance ledgers. Governments winked, easing deficits.

Qianlong’s rebuff severed not just commerce but modernity’s gateway. Had he engaged the innovations, dispatched learners? History might diverge. Instead, forty years on, 1840’s Opium War shattered isolation with gunboats. The once-boastful empire signed humiliating pacts, ceding sovereignty.

A Cautionary Relic in the British Museum

In the British Museum’s Asian galleries, the letter endures: yellowed rice paper, precise script, elegantly framed. Visitors pause, plaques narrating its pivotal role in East-West rupture.

Chinese onlookers sigh at ancestral oversight; Westerners muse on cultural chasms. Universally, it warns: Nations blind to evolution, mired in bygone splendor, court ruin.

Qianlong, dying at 89, clung to protocol as duty. Unwittingly, his words fueled Qing analyses, enshrined in a former “barbarian” trove. Beyond artifact, it’s mirror to hubris, tocsin for openness, primer on the harsh truth that backwardness invites subjugation.

History’s irony: A seal of majesty unveiled frailty. Retrospect isn’t blame, but vigilance: Underestimate change, overestimate strength at peril. Embrace learning to endure.

References

- British Museum Collection: Satirical print on the Macartney Embassy (1868,0808.6228).

- Georgian Papers Programme: Asian State Letters, including Qianlong’s reply (2022).

- Wikipedia: Macartney Embassy.

- Fordham University: Modern History Sourcebook, Qianlong’s Letter to George III.