Zhao Si, born Zhao Yidi in 1912, navigated a life marked by scandal, resilience, and quiet devotion amid China’s turbulent 20th-century history. As the illegitimate daughter of a high-ranking official, her path intertwined with warlord Zhang Xueliang, evolving from forbidden romance to a half-century of steadfast support. This tale of Zhao Si’s biography reveals a woman who thrived in adversity, embodying grace under pressure.

Early Shadows: An Illegitimate Heir in Colonial Hong Kong

On May 28, 1912, Zhao Yidi entered the world in Hong Kong’s British colony, daughter of Zhao Qinghua—a powerful Beiyang government transport deputy overseeing Shanghai-Nanjing and Beijing-Hankou railways—and his maid-turned-concubine Lu Baozhen. Hailing from Zhejiang’s Lanxi, the family lived modestly in Kennedy Town’s cramped quarters, far from Zhao Qinghua’s legitimate wife and children in mainland China. Those half-siblings viewed her with cold detachment, a rift that deepened over time.

At age 10 in 1922, she relocated to Tianjin with her father, trading narrow alleys for the opulent foreign concessions. Yet familial awkwardness persisted. Educated at Zhejiang Primary and Zhixi Girls’ Middle School, she honed English, music, and etiquette under structured tutelage. Zhao Qinghua’s ventures, like Beijing’s Fragrant Hills Hotel, brought prosperity, but as a illegitimate daughter, Zhao Yidi’s position remained precarious—learning household chores from her mother while brushing elite social circles at subdued tea parties.

Her 1926 Beiyang Pictorial cover—elegant in qipao, bare-faced—drew praise from Shenyang papers: “Like a peony, vibrant yet refined, noble without arrogance.” It hinted at her poised allure, even as home tensions simmered.

Familial Fracture: Disownment and Defiance

Zhao Qinghua’s strict oversight clashed with his daughter’s growing independence. Servants handled domestic reins, but Zhao Yidi absorbed upper-class nuances amid Tianjin concession vibrancy. The breaking point came in March 1928: A Dagong Daily notice severed their father-daughter ties, coinciding with his resignation. Enraged by her liaison with married Northeast Army commander Zhang Xueliang, he expelled Lu Baozhen to Qinhuangdao with son Zhao Guoliang. Half-siblings shunned her outright; only brother Zhao Yansheng offered discreet aid.

This family disownment scarred deeply, branding Zhao Yidi with the “illegitimate” stigma she carried lifelong. Yet it forged her tenacity—cut from inheritance, she faced biases head-on, a survivor schooled in Republican-era China‘s undercurrents. Her siblings’ mediocrity underscored her outlier status; entangled with Zhang, she became a historical linchpin, her domestic drama forcing an all-or-nothing resolve.

Forbidden Flames: The Zhang Xueliang Romance Ignites

Their story sparked at a 1928 Tianjin Cai residence dance: 16-year-old Zhao Yidi met 27-year-old Zhang Xueliang, via alleged kin冯永越 (later denied). The Northeast deputy commander, wed to Yu Fengzhi, showered her with books and blooms, prompting Zhao Qinghua’s fury. Undeterred, Zhao Yidi eloped to Shenyang in September 1929, entering Zhang’s household as a secretary. Kneeling before Yu, she vowed no title, just proximity—Yu relented, funding a discreet annex dubbed “Zhao Si Mansion.”

In November 1930, amid the Central Plains War, she bore son Zhang Lulin alone, raising him frugally while Zhang juggled battles. She cautioned the boy on discretion, shielding him from political whirlwinds. In Shenyang, Zhao Yidi managed military secrets—codes, dispatches—earning Zhang’s trust. He enrolled her at Fengtian University; she balanced studies and duties in lean times.

The 1931 Mukden Incident shattered illusions: Zhang’s non-resistance policy lost Manchuria, branding her a “femme fatale” in public scorn. She stood firm, enduring backlash.

Trials of Loyalty: Xi’an Incident to House Arrest Endurance

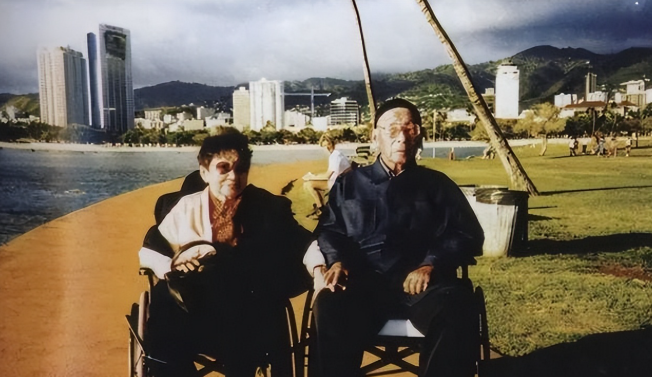

During the December 1936 Xi’an Incident—Zhang detaining Chiang Kai-shek—Zhao Yidi relayed classified wires. Post-coup, Zhang’s internment began; she fled Nanjing with their son, then Hong Kong, sustained by his funds. Yu Fengzhi joined Zhang in January 1937. When Yu sought U.S. cancer treatment in 1940, Zhao Yidi assumed caregiving in Guizhou’s Yangming Cave—harsh confines under guards, limited to five-kilometer radii. She tended gardens, raised fowl, transforming drudgery into devotion over 54 years of Zhang Xueliang house arrest.

From aide to de facto spouse, she sought no formal status, navigating the trio’s delicate dynamic.

Late Vindication: A Marriage After 37 Years

Yu Fengzhi, ever gracious, fretted over scandal but warmed to Zhao Yidi’s sincerity. Their tangle endured until 1964: Zhang’s Christian conversion clashed with polygamy bans; Chiang leveraged it for divorce pressure. Zhao Yidi lobbied Yu, framing it as Zhang’s wish—Yu acquiesced for his security, insisting coercion. On July 4, 1964, in Taipei’s Shilin Church, they wed modestly before a dozen guests. Yu, after three months’ deliberation, blessed their union: “For his twilight peace.” After 37 years’ wait, Zhao Yidi claimed her legal wife title.

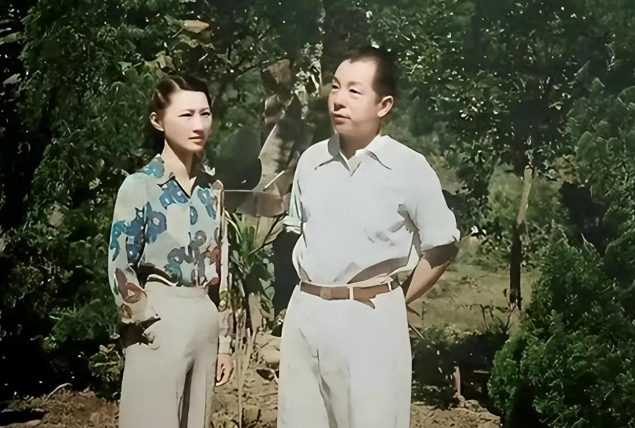

Beyond the Screen: Zhao Si’s Real-Life Grace

Pop culture paints Zhao Si with dramatic beauty—bold brows, striking eyes—but archival photos tell a subtler truth. Slender and elongated-faced, her fair skin framed refined features: Willow-thin brows, almond eyes with subtle upturns, high cheekbones, and naturally lined lips. No petite ideal by modern standards, yet her poised, cool elegance endures—serene, not showy. That 1926 cover captured it: Dignified in qipao, evoking the press’s “peony” poise—vivid, elegant, unpretentious.

References

- Historical biographies from “Zhang Xueliang and Zhao Yidi” archives (Taiwan National Archives, 1960s-1990s).

- Republican-era media clippings, including Beiyang Pictorial (1926).