Whenever the 2001 South China Sea collision incident comes up in conversation, it still evokes deep sorrow among Chinese people, even after more than two decades.

On April 1, 2001, a U.S. EP-3 electronic reconnaissance aircraft, without China’s permission, intruded into airspace southeast of Hainan Island for illegal intelligence gathering. This was no ordinary aircraft—it carried advanced surveillance equipment. The Bush administration, newly in office, had already begun to treat China as a strategic competitor, stepping up military operations around China. The EP-3 was part of this probing effort.

China quickly scrambled two J-8II fighter jets to intercept—one piloted by Wang Wei (aircraft number 81192) and the other by Zhao Yu. Wang, then a Navy lieutenant commander and first-class pilot with over 1,000 flight hours, was highly experienced. At around 104 km southeast of Hainan, they intercepted the U.S. aircraft.

Initially, the U.S. plane appeared to retreat, but soon turned back provocatively. Wang closed in—just three to four meters away—and signaled them to leave. Suddenly, the U.S. plane made a sharp turn; its left wing and propeller struck the tail of Wang’s fighter.

The J-8II spun out of control. At 9:07 a.m., Wang ejected successfully, but after landing in the sea, he was never seen again. Zhao Yu witnessed the entire event and reported the coordinates while continuing to shadow the damaged U.S. plane, which later made an unauthorized emergency landing at Lingshui airport. China detained the 24 U.S. crew members.

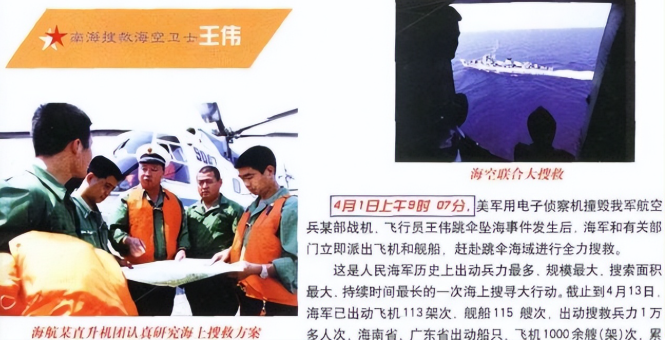

Massive Search, No Result

China reacted swiftly. The South Sea Fleet launched a large-scale rescue operation:

- Over 100,000 personnel, including military and civilians

- 1,000+ aircraft sorties

- 115 naval vessels

- Search covering 300,000 square kilometers

For 14 days, forces conducted grid searches, with low-flying aircraft, naval ships, and even fishing boats scanning the sea day and night. Yet, not a trace of Wang was found—nor were significant wreckage pieces recovered.

By April 14, the search was scaled down, and on April 24, the Central Military Commission posthumously honored Wang Wei as a revolutionary martyr. Countless people mourned at his memorial.

Why Couldn’t They Find Him?

Only with hindsight, in 2025, do we understand the reasons:

- Harsh Ocean Conditions

The South China Sea has deep waters, strong currents, and turbulent waves. A parachuted pilot would drift rapidly. Sun glare and water refraction hampered visibility. High surface tension and waves could easily pull a person under. - Ejection Impact

The J-8II used an HTY-4 rocket ejection seat. While Wang did eject, the violent shock may have knocked him unconscious, preventing him from activating survival signals. The seat’s locator was imprecise, offering only a broad area. - Limited Rescue Technology in 2001

China’s Beidou satellite navigation system was in its infancy—only two trial satellites existed, with no South China Sea coverage. GPS was U.S.-controlled and unreliable for Chinese forces. Without modern satellite positioning, search teams relied on manual sweeps. - Lack of Professional Equipment

Rescue relied mainly on navy and air force units, not specialized maritime search teams. Helicopters had short range, naval ships were slow, and weather disrupted operations. Civilian fishing boats lacked professional tools, making coordination difficult.

By contrast, today’s China has full Beidou coverage, UAVs, infrared imaging, and high-precision satellite monitoring—all unavailable in 2001.

Diplomatic Fallout

The U.S. crew destroyed sensitive data before their forced landing. During negotiations, the U.S. sent six letters, expressing “regret” but avoiding a direct apology. On April 12, China released the crew; the dismantled EP-3 was returned on July 3.

China insisted the collision was caused by the U.S. plane’s reckless maneuvering. The U.S. countered that Wang flew too close. Regardless, the U.S. intrusion clearly violated international maritime law.

Broader Lessons

The tragedy highlighted the difficulty of maritime search and rescue—similar to the later MH370 disappearance. In Wang’s case, strong currents, limited technology, and possible injuries sealed his fate.

It also spurred China’s military modernization. The KJ-2000 early warning aircraft program was accelerated after the incident, strengthening China’s ability to monitor airspace.

Today, the number 81192 has become a symbol of sacrifice. Wang Wei’s loss reminds us that peace is hard-won, and sovereignty must be defended.

References

- Xinhua News Archives, April 2001

- Ministry of National Defense of China, South Sea Fleet Reports

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Articles 56 & 301