In humanity’s history of harnessing natural resources, some tales sound like legends. Take the underground coal fire in Xinjiang’s Sulfur Groove: it raged from the Qing Dynasty’s Guangxu era (1874) into the early 21st century, consuming a century and a half. It caused over 1 trillion yuan in economic damage and displaced countless herders from their lands. Yet, this “underground fire dragon” was ultimately tamed by Chinese ingenuity, blooming in unexpected ways. How did it start? Why couldn’t generations extinguish it? And how was it finally conquered? Let’s dive into this 129-year saga.

Why the Fire Was Unquenchable

The story begins in 1874, when Qing troops mined coal in Sulfur Groove using primitive methods, exposing seams to air. Xinjiang’s arid climate made oxidation inevitable: coal heats up on contact with oxygen, and at a certain point, it self-ignites. A small spark burrowed into the seam, igniting a century-long blaze.

Sulfur Groove’s geology sealed its fate. Tectonic shifts tilted coal seams, leaving many exposed or shallow, like open powder kegs. The low-rank coal, high in moisture and volatiles, burned easily. Underground faults and cracks acted as natural “ventilation pipes,” drawing in oxygen to fuel the flames. At its peak, the fire spanned 200 square kilometers, filling the air with acrid sulfur and toxic gases like carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide. Livestock sickened from contaminated water, grasslands charred, soil hardened, and vegetation vanished. For locals, this “fire dragon” wasn’t just a resource thief—it was a catastrophe.

Before 1949, no one had the means to fight it. In 1958, geological teams first documented it systematically, but early efforts like sealing cracks with mud slurry were crude. They blocked air but couldn’t handle the complex underground maze; flames always found new paths. For decades, humanity was at the fire’s mercy.

Generations of Struggle and Breakthrough

The tide turned post-1978 reforms, as economic growth bolstered research. Specialized coal fire teams experimented with innovations: injecting nitrogen to displace oxygen, digging firebreaks to isolate flames, and using controlled blasts to disrupt coal continuity. These were more scientific, but the fire’s scale and heat (up to hundreds of degrees Celsius) limited access—workers relied on machinery.

By 2000, the state committed to ending this “century-old scourge.” The Sulfur Groove coal fire project became a national priority, backed by nearly 100 million yuan and top geologists and miners. The game-changer: high-tech tools. Satellite remote sensing pinpointed hotspots, drones monitored flames, geological radar mapped underground structures, and infrared devices tracked temperatures. For the first time, experts had a “clear view” of the fire’s layout—turning blind combat into targeted strikes.

The strategy: divide the field into 18 sub-zones, tackling 14 easier ones first for experience, then the toughest four. A “combo punch” followed: drill and seal air channels with grout, inject nitrogen to cool, dig firebreaks, and blast to fragment coal. After three years of battle, the 129-year fire was extinguished in 2003.

The victory saved 1.5 billion tons of coal and prevented further losses. For generations of scientists and workers, it was the culmination of decades of perseverance.

Revival After the Flames

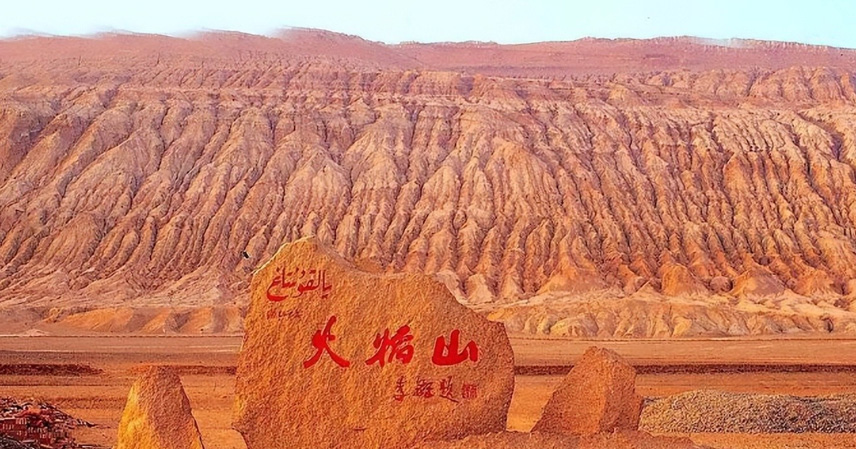

Many expected Sulfur Groove to become a wasteland, but nature rebounded. Without smoke and toxins, subsidence was filled, cracks sealed, and air cleared. Vegetation sprouted, red sandstone gleamed under the sun, and surrounding farmlands regained fertility, boosting crop yields. Groundwater purified, herders returned to graze.

From “hellish inferno” to “idyllic pasture,” the land transformed. Its unique geology now draws tourists seeking the Journey to the West “Flame Mountain” inspiration and post-fire wonders. The government developed it into a National Geopark and 4A scenic area along Highway 312, spurring local economy.

But the story didn’t end with extinction. Scientists at China University of Mining discovered residual underground heat. They innovated coal fire residual heat power generation: drill to tap heat, convert temperature differences to electricity. Clean and water-efficient, it’s ideal for arid Xinjiang. Tests show a single borehole generates 2,105 watts, and 100 could produce over 100,000 yuan annually. Though modest, it turns disasters into resources.

Globally, underground coal fires burn ~1 billion tons yearly. Sulfur Groove’s success offers a blueprint.

Conclusion

This fire, from 1874 to 2003, devoured billions of tons of coal and challenged generations. China’s determination and ingenuity extinguished it, reclaiming resources and reviving the land. Today, Sulfur Groove is a hub for tourism, ecology, and clean energy—not a “hellfire sea.”

Looking back, it teaches: humanity may seem small against nature’s fury, but persistence finds harmony. Could the world’s other “underground fire dragons” meet the same fate?