The real palace life is not the dramatic intrigue of TV dramas, but oppression by “rules” and torment by “loneliness.” Daily distribution of 12 jin of meat looks like luxury, but behind it is the iron cage of the system and the shackles of hierarchy. Visiting prohibited, one item per person to relieve boredom, all have reasons, and the logic behind is far calmer and crueler than eating and dressing.

Distributing a lot of meat is not luxury, but “unified supply” under rules

Flipping through the Qing palace “Shan Di Dang,” the tables list clearly which concubine gets how much meat per day, what meal serves chicken, duck, fish, every gram is planned. For example, the empress gets 16 jin of pork, 1 jin of mutton, one chicken and one duck per day; the imperial consort gets 12 jin; consorts, imperial concubines, noble ladies decrease gradually. The numbers are eye-popping, a woman eating over ten jin of meat a day? It’s not made up, this is the standard copied from archives.

What can’t be eaten is really uneaten. How much actually enters the mouth depends on how you “divide.” This portion of meat must also be shared with serving palace maids and attending eunuchs, and processing requires arranging the kitchen yourself. This is not a simple eating problem, but an extension of the entire hierarchical system. Meat is identity, the symbol of the consort position.

Using meat to mark grades is actually the simplest and crudest management method in the imperial palace. Not giving you power, but letting you eat “like a decent person,” so outsiders see “oh, so much meat, treatment not low,” that’s enough. This “good life” is actually not free, not comfortable.

Meat comes every day, every day. Can’t eat it all, still comes, want to lose weight? Sorry, the system doesn’t write “calories,” it writes “must not stop supply.” Can’t eat? Can reward people, but reward too much must report. People in the palace are not looking at how much you eat, but who you give to, how you divide, if there’s suspicion of forming cliques.

Some palace consorts can’t eat the meat, simply dry it into jerky, store it long-term, when meeting relatives or rewarding, can “pack.” Some smart people use meat to exchange for silk, spices, forming “meat ticket” trading, but this is a secret, if discovered, it’s a big taboo, because it touches the system’s red line—private trading disrupts unified supply.

Those once-favored but fallen from grace, their meat portions are cut, from 12 jin to 6 jin, or even less. This is not just about eating less, but a public humiliation, telling everyone: your position has dropped, your identity has changed.

Distributing meat is not feeding people, but feeding the system. It makes sure every consort “looks like” living the life she should, but actually, it’s a cage, letting you eat meat but not letting you be full.

Visiting prohibited, not for preventing intrigue, but for maintaining “order”

The palace rule is strict: consorts are not allowed to visit each other casually. Visiting? Must apply, get approved, have records. Why? Not just to prevent intrigue and jealousy, but to keep the palace’s “order” from chaos.

The palace is a huge machine, every consort is a part, with her own position, her own circle. If visiting is free, low-rank visits high-rank, is it flattering? High-rank visits low-rank, is it showing favor? One careless move, and the balance is broken. The emperor doesn’t want to see consorts forming groups, nor does he want rumors flying.

So, visiting prohibited is to isolate everyone. You live in your palace, I live in mine, meet only at please-an or banquets. This way, no one can easily ally, no one can spread gossip. Loneliness? That’s the price, the system wants you lonely, so you rely more on the emperor.

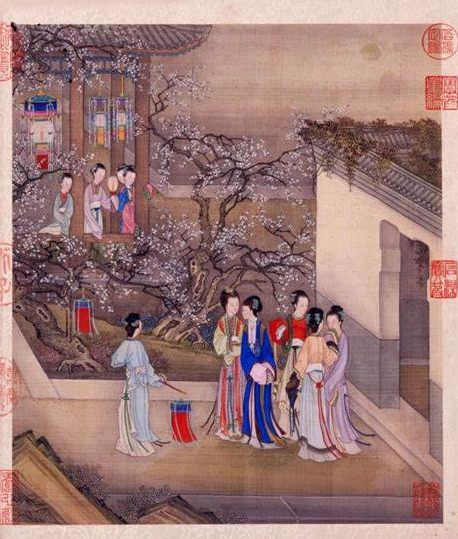

Some consorts, to relieve boredom, raise flowers, read books, embroider, but these are all solitary activities. No group games, no chatting tea parties. The palace is big, but space is small; people are many, but hearts are far.

One item per person to relieve boredom, not kindness, but calculated “pacification”

The system knows consorts are bored, so each gets one “relief item.” What? A parrot, a cat, a dog, or a cricket jar. Sounds like companionship, but actually calculated.

Why one? Because more might cause trouble. A parrot talks, but if it learns wrong words, trouble. A cat or dog runs around, if enters the emperor’s study, bad luck. The item is to let you have something to do, but not too much, just enough to pass time, not enough to cause waves.

Those favored get rare birds; those out of favor get a cricket. This is also hierarchy. The relief item is not for happiness, but to let you “self-entertain,” not bothering others, not thinking of rebellion.

Some consorts use the item to vent: talk to parrots, play with cats. But if the item dies, it’s an omen, might bring punishment. Even relieving boredom has risks.

The palace surface dignity is not warmth, but hard support under layers of restrictions. Even with several dishes, over ten jin of meat, gold silk curtains, it’s hard to hide the dryness in life.

Consorts many, favor few, is the palace norm. The less favored rely on the system to live. Days like attendance, what time to rise, greet, copy scriptures, burn incense, all written in daily notes. If you forget a step, the record becomes “evidence.”

On the surface, many concubines, but actually only two or three can often see the emperor. Most mix days in the harem, not competing for favor, not causing trouble, just seeking stability. Dare not get sick, dare not err, dare not have dreams. Even crying must choose a time no one hears.

Some noble ladies enter the palace for over ten years, haven’t seen the emperor’s shadow several times, year by year age increases, year by year waiting becomes empty. Even eating twelve jin of meat, hard to dispel heart loneliness. Those granted gold and silver vessels, embroidered palace clothes, all piled in the room with no one to appreciate, like a warehouse, not like home.

The existence of the cold palace is not just punishment, but the system’s deterrence. Whoever dares to err, the next moment might be sent to the cold palace, from then silent. Eating reduced, wearing rough, people forgotten, even “daily twelve jin meat” becomes a distant legend. No one dares approach the cold palace, because it’s inauspicious, and because that’s a “living worse than dead” symbol.

The harem is like this: bustle is appearance, loneliness is truth. People many, but can’t get close; things rich, but can’t be free; rules a bunch, but don’t care if you’re happy or not.

If comparing this system to a pot of exquisite Manchu-Han full banquet, the concubines are pieces of stewed ingredients, seasoned, served, evaluated, solely not cared if they can eat or not.

When old age comes, few leave the palace, most buried in silence. Silent, no waves, only palace walls remember their numbers and the halls they lived in, like a page written and erased by the system. This is the harem daily: not competing for favor and intrigue, but eating meat can’t relieve boredom, living but never seen.