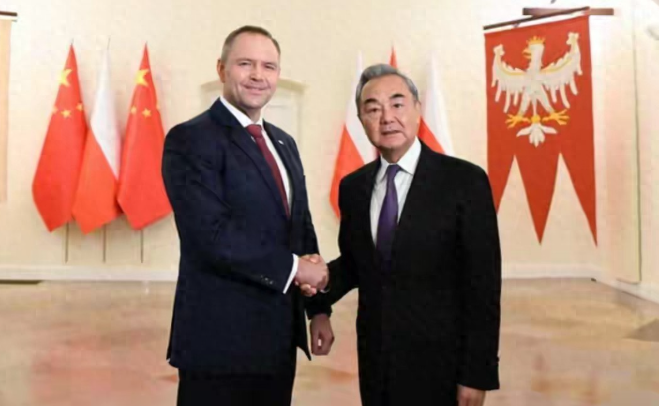

No one expected this: just days after warmly hosting Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and jointly pledging to “ensure the smooth operation of the China-Europe Railway Express,” Poland suddenly flipped its stance.

Soon after the visit, Warsaw broke its promise, announcing that all Poland–Belarus border crossings—closed since September 12—would remain “indefinitely shut.”

This was not just about shutting down a few checkpoints; it effectively choked off the most crucial land logistics artery between China and Europe.

Why is Poland’s move so critical?

As the flagship project of the Belt and Road Initiative, the China-Europe Railway Express has become one of the busiest international logistics corridors on the Eurasian continent. Unlike air freight, it is cost-effective; unlike sea shipping, it is much faster. This makes it ideal for high-value goods such as electronics, auto parts, and cross-border e-commerce parcels.

At the heart of this corridor lies the Malaszewicze crossing on the Poland–Belarus border—the railway’s “throat.”

Data shows that more than 85% of China-Europe freight trains pass through this gateway to enter Europe, before being distributed to over 220 cities across 26 countries, including Germany, France, and Italy.

Now, with Poland suddenly cutting off this lifeline, the consequences are immediate:

- About 300 trains are stranded in Belarus.

- Large quantities of goods, including electronics, solar components, and auto parts, are stuck in limbo.

- Supply chain costs have surged by over 15%, with many European firms already complaining.

- The EU’s supply chain monitoring center issued a direct warning: the shutdown could impact trade worth up to €25 billion.

Is “security” the real reason?

Poland’s stated justification was “national security”: citing threats from the Russia-Belarus joint “Zapad-2025” drills and incidents of drones crossing the border.

But the background tells a different story.

During Wang Yi’s visit, Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski openly demanded that China “urge Russia to halt hybrid operations against Europe’s eastern flank.”

The keyword here—“hybrid operations”—refers to non-traditional threats like intelligence activities, cyberattacks, and refugee crises. What Poland truly wanted was for China to take sides in the Russia-Ukraine conflict and pressure Moscow.

China, consistently advocating peace talks and neutrality, naturally rejected this demand.

As a result, Warsaw turned the China-Europe Railway into a geopolitical bargaining chip.

But does this move really work?

China’s response: calm, with backup plans already in place

The very next day after Poland’s announcement, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman stated that China is ready to work with Russia and other Arctic states to promote international cooperation and sustainable development along the Arctic shipping route.

A brief remark, but the signal was clear:

Poland may try to close the channel, but China has the confidence to open new ones.

The Arctic Route — China’s “Northern Wing”

As global warming accelerates Arctic ice melt, the “Northeast Passage” is becoming commercially viable.

This route runs from China’s coast, through the Bering Strait, along Russia’s northern waters, and straight into Europe.

Compared to the traditional South China Sea–Malacca–Suez Canal route, it shortens the distance by nearly 30%, saving 10–15 days in transit time. Beyond cost and time savings, its biggest advantage is independence—it avoids chokepoints and geopolitical traps.

China has long prepared for this.

- In 2013, China became an observer of the Arctic Council.

- In 2018, Beijing released a White Paper on Arctic Policy, proposing the “Polar Silk Road.”

- On September 20, 2024, Ningbo Port launched its first trial voyage via the Arctic route, actively exploring regular operations.

Though challenges remain—limited navigation seasons, high icebreaking costs, and insufficient infrastructure—the route represents a decade-long strategic bet. Once fully operational, China will have a secure, autonomous alternative route to Europe.

The Southern Corridor: Middle Corridor & China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway

China is also looking westward.

The Middle Corridor (Trans-Caspian International Transport Route) runs from China through Kazakhstan, across the Caspian Sea, then via Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey into Europe.

Crucially, it bypasses Russia, Belarus, and Poland altogether—making it a genuine southern alternative.

In recent years, China has stepped up cooperation:

- September 2023: multiple agreements signed with Kazakhstan.

- July 2024: joint declaration with Azerbaijan on Middle Corridor development.

Though its current capacity is only 6 million tons annually, the four countries—Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey—have agreed to double this to 12 million tons by 2027.

Meanwhile, critical infrastructure such as Caspian Sea rail ferries came online in late 2025, rapidly boosting efficiency.

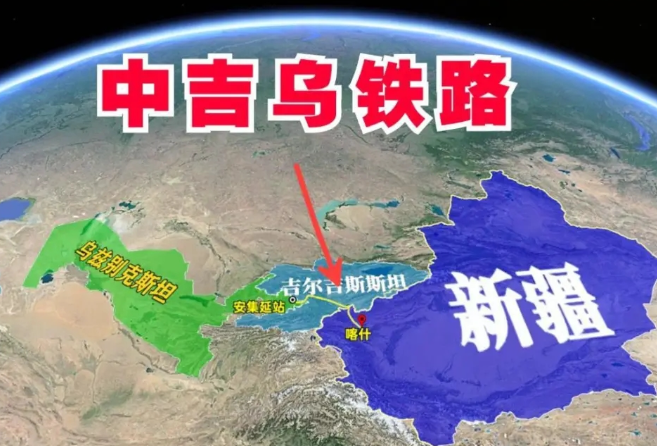

China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway

After nearly 30 years of delays, construction officially began in July 2025.

Starting from Kashgar, the line crosses Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, then connects into the Iranian and Turkish rail networks before reaching Europe.

The project uses mixed Chinese standard-gauge and broad-gauge tracks, with China holding 51% equity and control.

Once completed by 2031, the line will shorten China-Europe freight distance by about 900 km, saving 7–8 days in transit. Most importantly, it will fundamentally reduce dependence on the northern route through Russia, Belarus, and Poland.

The big picture: China never puts all its eggs in one basket

Poland may think closing its borders gives it leverage. But it underestimates China’s foresight and resilience in strategic route planning.

From the Arctic passage to the Middle Corridor to the CKU Railway, China is building a “multi-directional closed-loop system”:

- Northern route (via Poland): currently dominant, but geopolitically fragile.

- Arctic route: future-oriented, fully autonomous.

- Southern corridor (via Central Asia & Turkey): accelerating, with strong substitution potential.

This system ensures that even if one artery is blocked, China’s trade will not suffer a fatal blow.

Poland’s closure reflects not security concerns, but strategic shortsightedness.

Global supply chains are public goods, not political weapons. Weaponizing logistics corridors damages national credibility and long-term interests.

China’s approach proves an old saying: “Success comes from preparation; failure from lack thereof.”

After a decade of preparation, China’s new trade channels are already reshaping the future of global logistics.

Great power competition is not about who shouts louder, but about who plans further and stands firmer.

References

- Xinhua, CGTN reports on Poland’s closure of border crossings and China-Europe freight delays.

- TASS, Kyiv Post coverage on Ukraine-related developments.

- Financial Times investigation on U.S. pressure over Chinese port operations.