At the beginning of 2025, the U.S. Department of Commerce suspended the supply of LEAP-1C engines to China’s C919 passenger jet, citing “national security concerns.”

However, on August 21, Sergei Chemezov, CEO of Russia’s state-owned Rostec Corporation, announced in front of Sputnik cameras:

“If there is demand, we are ready to provide China with Russian aircraft engines.”

This bold statement immediately sparked speculation: Does this mean China no longer needs to fear being “choked” by U.S. restrictions? Can Russian engines really serve as a substitute?

Russia’s Offer

Earlier in September, Russian First Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov told reporters that Russia was prepared to supply components for China’s wide-body aircraft, including composite wings and heavy engines.

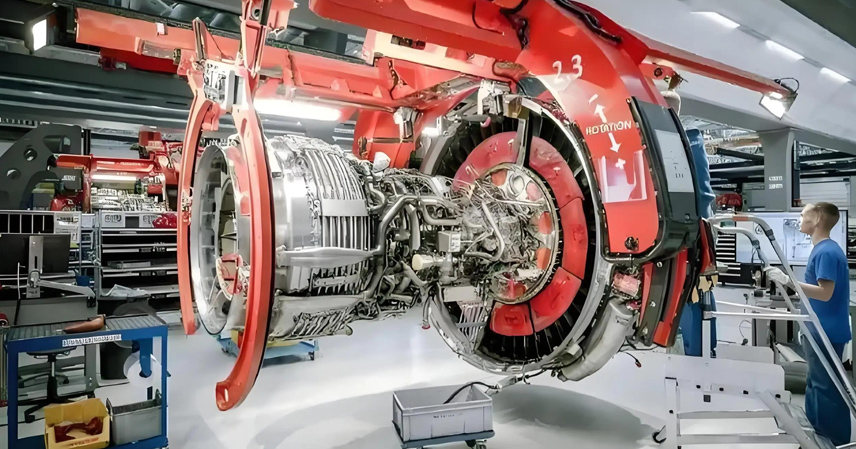

He highlighted that Russia’s strength lies in projects like the MC-21, with engines such as the PD-35, a heavy gas-turbine engine with 26–35 tons of thrust. This engine is currently being developed for military transport aircraft like the Il-100, as well as potential civilian models such as the MS-21-500 and MS-600.

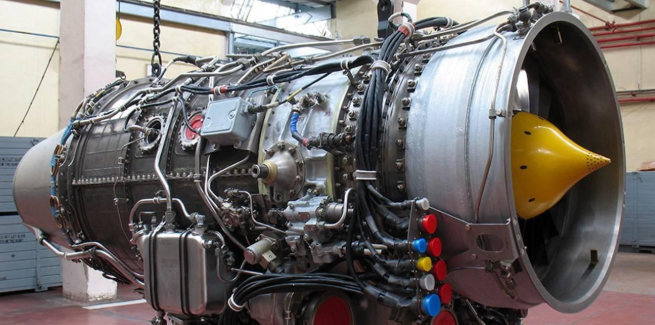

Russia indeed has a full range of engines:

- PD-8 (regional jets)

- PD-14 (medium thrust, 14 tons)

- PD-35 (large thrust, 26–35 tons, still under development)

The PD-35 is Russia’s largest civil aviation engine project and was originally linked to the China-Russia CR929 wide-body program.

Yet, there are caveats: Manturov himself admitted that the PD-35 will need another 2–3 years to complete development, meaning it is not immediately available. Furthermore, Russia’s production capacity is limited due to aging factories, inconsistent supply chains, and uneven engineering expertise. Even if the technology is viable, the stability of supply and maintenance remains questionable.

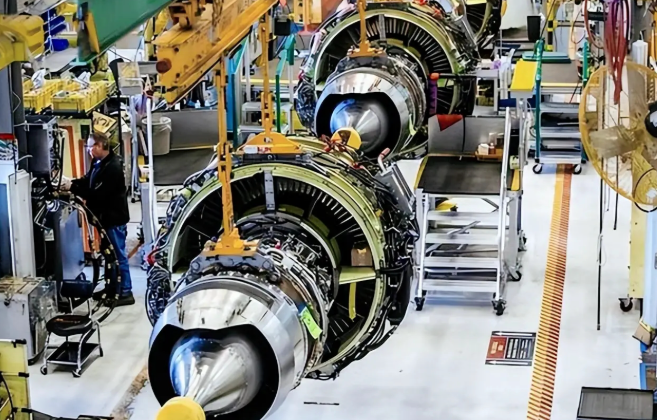

Integration is another challenge. Installing a new engine on the C919 is not as simple as swapping hardware. It requires adjustments in aerodynamics, pylons, weight distribution, propulsion control systems, monitoring equipment, and ground infrastructure. Since the C919 was designed and tested around the LEAP-1C, switching to the PD-14 or PD-35 would require expensive and time-consuming redesigns.

The Strategic Context

Russia’s offer is not just about selling engines—it is also a geopolitical move. Facing Western sanctions, Russia’s aviation industry is in crisis. According to data, 70% of Boeing and Airbus spare parts are in shortage, causing Russia’s flight punctuality rate to collapse to 41% in 2025.

Meanwhile, the U.S. is deliberately restricting China. In May 2025, the U.S. Commerce Department froze all new export licenses for aviation engine technology to China, calling it a “strategic move to contain China’s civil aviation development” (New York Times).

Thus, Russia’s move serves two purposes:

- Gain revenue and market share by selling engines.

- Strengthen ties with China to jointly resist Western technology blockades.

China’s Own Progress

For China, Russian engines might provide a temporary backup, but they are not a long-term solution. China’s strategy is to accelerate domestic engine development.

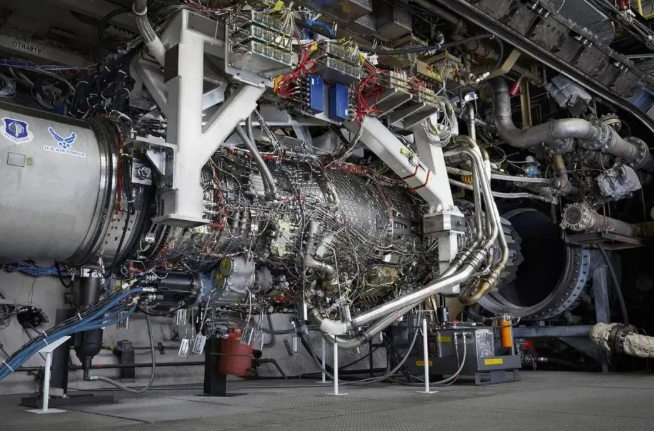

- The CJ-1000A “Changjiang” engine, designed for the C919, has already passed 6,142 hours of extreme testing, including surviving turbine inlet temperatures of 1,500°C, breaking Western durability records. It is reported to be 7% more fuel-efficient than comparable U.S. products.

- According to COMAC experts, the CJ-1000A is 9 months ahead of schedule, with airworthiness certification expected by late 2026.

- Beyond that, the CJ-2000 wide-body engine has entered critical testing phases, with improvements in fuel efficiency and noise reduction close to international standards.

By 2030, Chinese aviation experts project that domestic engines will cover 50% of civil aviation needs, significantly reducing reliance on foreign suppliers like CFM and Rolls-Royce.

Conclusion

Russia’s offer is a short-term buffer, not a permanent solution. While the PD-14 and PD-35 may serve as interim alternatives, they come with integration challenges and uncertain production reliability.

China, on the other hand, is rapidly moving toward self-sufficiency in aviation engines, with the CJ-1000A and CJ-2000 projects marking significant breakthroughs.

In the long run, the real safeguard against being “choked” is not Russian assistance, but China’s own independent innovation.

References:

- New York Times, U.S. Commerce Department internal documents on aviation technology export bans (2025)

- Financial Times, May 2025 report on U.S. Entity List considerations for Chinese aviation

- COMAC Research Institute, progress reports on CJ-1000A and CJ-2000 engines

- Russian Ministry of Industry and Trade, MC-21 and PD-35 project updates