It’s a twist of irony: Japan spent over a decade trying to break free from its reliance on Chinese rare earths. Billions of dollars were poured into technology and exploration, yet breakthroughs never came.

Unexpectedly, all those failed attempts became a “cautionary tale” that paved the way for China’s own rare earth breakthrough. What was meant to trouble China instead turned into a ladder for China to climb past a decades-long bottleneck.

Japan’s Deep-Sea Gamble Turns Into a Costly Failure

Rare earth elements (REEs) may sound obscure, but they are as critical as oil. From smartphones and wind turbines to missiles and maglev trains, modern technology depends on them.

Japan, a global manufacturing powerhouse, has long been a classic case of “rare earth dependence.” With no significant domestic deposits, it imported over 90% of its needs—mostly from China.

Worried about this vulnerability, Japan launched a bold initiative in 2012: exploring the seabed near Minamitorishima (Marcus Island).

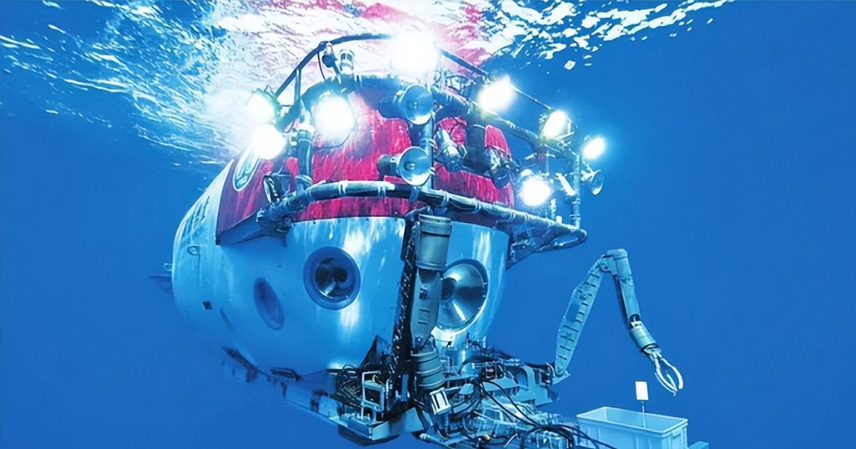

To Japan’s delight, surveys revealed seabed mud rich in rare earths. Some estimates suggested that the deposit contained enough dysprosium to supply the world for centuries. Tokyo quickly mobilized funds, rolled out subsidies, waived taxes, and even commissioned a futuristic mining ship, Chikyu-go, equipped with AI-powered robots capable of diving 5,000 meters.

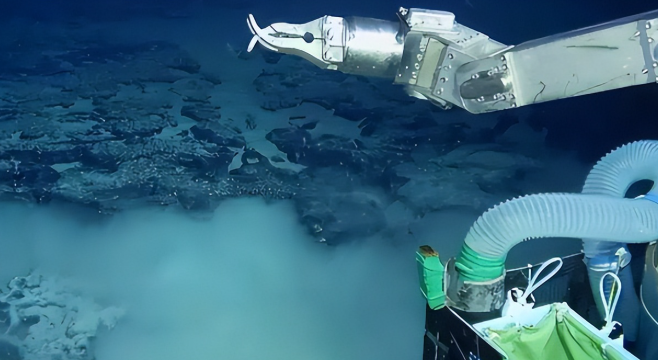

But reality was far less glamorous. Each kilogram of rare earth required disturbing 10 tons of seabed sludge—at costs eight times higher than the global market price. Six-thousand-meter pipelines snapped under pressure in stormy waters. Mining vehicles slipped helplessly on the seabed floor.

At peak operations, Japan was burning through $2 million a day. Eventually, companies could no longer shoulder the losses, and the project stalled.

What Japan ended up with was not independence from Chinese rare earths, but rather a collection of failures—ironically, a “deep-sea mining case study” that China would later learn from.

China Watched Closely—and Learned Strategically

While Japan was struggling, Chinese researchers were paying close attention. Instead of rushing into deep-sea mining, they studied Japan’s experimental data, analyzed its technical pitfalls, and quietly developed solutions.

For example:

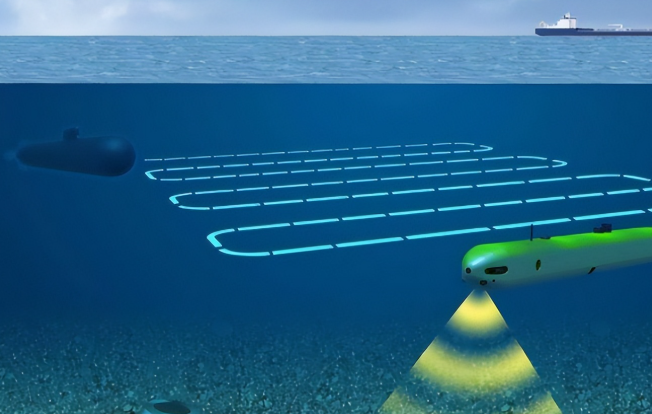

- Seabed mobility – Japan’s mining vehicles slipped constantly. Chinese engineers redesigned the tracks with special anti-slip patterns.

- Energy efficiency – Japan’s machines guzzled fuel. China switched to fully electric systems, capable of diving 6,000 meters while cutting energy use by 40%.

- Precision control – Japan’s systems had an error margin of 3 meters. By 2024, China’s “Kaituo-2” mining vehicle reduced that to just 10 centimeters.

But China’s advantage was not limited to extraction. The country developed a full-cycle approach:

- Recycling – Shenzhen’s e-waste facilities achieved a 92% rare earth recovery rate.

- Battery regeneration – CATL developed a process that recycles rare earths at 98% purity, lowering costs by more than 30%.

In short, while others were still digging in the ocean, China was “mining” old smartphones and batteries more efficiently. This shift allowed China to not only stabilize its supply but also climb the value chain—from exporting raw ores to controlling high-tech applications and pricing power.

Strategic Mastery: China Holds the Rare Earth “Water Tap”

Rare earths may be a cluster of obscure elements, but they represent a battlefield of global strategic competition. Japan’s failure was not just technological—it was strategic miscalculation.

China, by contrast, built a full-spectrum rare earth ecosystem: from exploration and mining to refining, processing, and recycling.

By 2023:

- China produced 70% of the world’s rare earths.

- It controlled over 90% of global refining capacity.

- Giants like China Northern Rare Earth Group and China Rare Earth Group dominated the domestic—and by extension, global—market.

Japan, despite its promising seabed deposits, has been unable to exploit them. Its joint recycling ventures with France cost 20% more and deliver lower efficiency compared to Chinese methods.

The United States, meanwhile, has repeatedly attempted to revive its rare earth industry. But projects in Arizona and elsewhere have yet to produce meaningful output, forcing the U.S. to continue importing up to 80% of its rare earth supply from China.

The result? While Japan sprinted ahead but stumbled, China advanced steadily, learning from others’ mistakes and ultimately pulling off a technological and strategic overtake.

From Technical Breakthrough to Strategic Leverage

Japan’s seabed mining failure was not wasted—it inadvertently became a free “research report” for China.

Instead of diving headlong into costly ventures, China chose a more sustainable path: strengthening extraction technologies, integrating the value chain, and innovating recycling methods.

Today, China not only extracts rare earths but also deploys them across critical industries—from EV motors and 5G chips to wind energy and satellite navigation.

This transformation—from merely “digging” to fully “using”—is the true source of China’s rare earth power.

And when China imposed new export controls on certain medium and heavy rare earths in 2025, the ripple effect was immediate. Western nations scrambled to secure alternative supplies. Yet without comparable resources, technology, or cost efficiency, most of these plans remain little more than political slogans.

China, meanwhile, has shifted from simply selling raw resources to exporting technology, standards, and entire systems. In essence, China is no longer selling rare earths—it is exporting capability.

Conclusion

Japan’s deep-sea rare earth gamble was meant to break free from China’s grip but instead turned into an expensive failure. Ironically, it became the very case study that allowed China to solve its own rare earth puzzle.

This success was not a stroke of luck, but the result of strategic patience, systematic innovation, and the ability to learn from others’ missteps.

In an era of intensifying resource competition, the nation that masters both technology and industry controls the future.

Japan may have unwittingly given China a helping hand, but it is China’s own vision and innovation that will determine how far it goes from here.

References

- Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) reports on seabed rare earth exploration (2012–2023).

- China Northern Rare Earth Group annual report (2023).

- CATL research on rare earth battery recycling (2024).