When examining the nature of aggression, it becomes clear why Japan stands out in China’s historical memory.

In the 19th century, many foreign powers came to China primarily for profit. The British, for example, waged the Opium War in 1840 to open Chinese markets and sell their goods, while also forcing reparations and territorial concessions. France, Russia, and others acted similarly—signing treaties, claiming minor advantages, or seizing resources—but they did not intend to annihilate the Chinese population.

Japan, however, was different. Beginning with the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, Japan not only won but directly annexed Taiwan and the Penghu Islands, demanding reparations of 200 million taels of silver—enough to build its navy. The Japanese army committed atrocities in places like Lüshun, killing tens of thousands of civilians, which shocked the international community. Unlike other aggressors who mostly plundered and left, Japan seemed intent on embedding itself permanently in China.

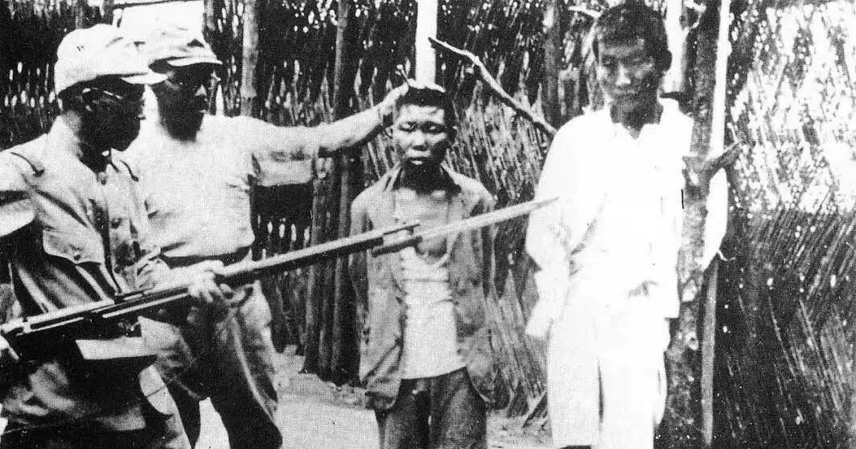

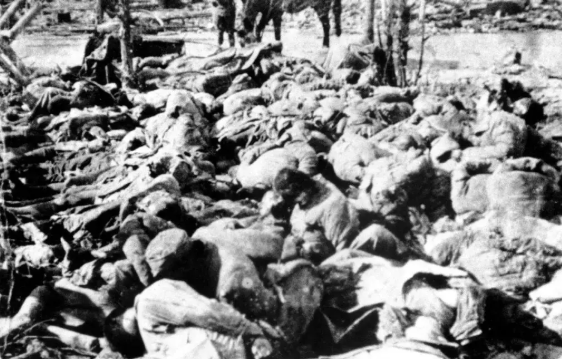

The invasion escalated with the 1931 Mukden Incident, leading to the occupation of Northeast China and the establishment of the puppet state Manchukuo. Japan sought total control, not mere territorial gain. During the full-scale war in 1937, Japanese forces implemented the “Three Alls Policy”—kill all, burn all, loot all—devastating villages across North China and causing massive civilian casualties. The Nanjing Massacre alone claimed over 300,000 lives, and Unit 731 conducted biological experiments on Chinese prisoners in Harbin. Japan’s aggression carried the hallmarks of ethnic extermination, far beyond mere economic exploitation.

Japan’s ambitions extended culturally as well. After the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, Japan began colonizing Taiwan, forcing locals to learn Japanese and adopt Japanese names. In contrast, the British in Hong Kong primarily pursued commercial interests, and France in Vietnam did not implement such intense cultural assimilation in China.

The scale of Japan’s atrocities is staggering. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, China lost over 20 million military and civilian lives, far exceeding casualties from other foreign aggressions combined. While historical grievances might fade over time if aggression were limited to territorial and financial demands, Japan’s brutal acts left an indelible mark.

Post-war attitudes worsened the resentment. Other countries have acknowledged their wrongdoings: the UK admits its errors in the Opium War, and France has reflected on its colonial history. Japan, however, has often wavered on historical issues. In the 1950s, Japanese textbooks described the invasion of China as merely “entering China.” In 1982, the Ministry of Education approved textbooks changing “aggression” to “entry,” sparking protests in China.

Japanese politicians have also aggravated tensions. Visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, which enshrines Class-A war criminals like Tojo Hideki, by figures such as former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, have repeatedly drawn Chinese diplomatic protests. Some scholars and politicians have denied atrocities outright: in 1998, Higashinakano Shudo claimed the Nanjing Massacre killed fewer than a thousand people. In 2020, MP Sugita Mio publicly called the massacre fabricated. Unlike Germany, which criminalizes Holocaust denial, Japan has not taken legal steps to counter historical revisionism.

Small contemporary actions continue to reinforce suspicion. Statements like Abe’s claim that “a Taiwan issue is a Japan issue” in 2021 effectively extend Japan’s security concerns to Taiwan. Diplomatic meetings with Taiwanese officials and joint military exercises in the South China Sea further exacerbate tensions. Attempts to influence international commemoration of China’s 80th Anti-Japanese War anniversary in 2025 also created friction.

Even territorial disputes persist. The 2012 “nationalization” of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands and subsequent patrols, as well as Japan’s involvement in South China Sea exercises, signal ongoing assertiveness. These cumulative actions convince many Chinese that Japan has not genuinely reconciled.

China’s resentment toward Japan is therefore deeply rooted. From the intensity of wartime aggression, to post-war denial and revisionism, to present-day provocations, the grievances have compounded over decades. Other foreign aggressors have largely moved past their invasions, but Japan’s actions prolong the memory of suffering.

Ultimately, Chinese resentment is not innate; it is a response to history. Hatred is not the goal—peace is. Reconciliation must begin with acknowledgment and respect for historical truth. Only when Japan genuinely confronts its past can mutual understanding and cooperation emerge. Until then, this question—why China seems to single out Japan—will persist.

References

- Xu, Guoqi. China and the Japanese Empire: The History of Sino-Japanese Relations. Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Chang, Iris. The Rape of Nanking. Basic Books, 1997.

- Peattie, Mark. Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power, 1909-1941. Naval Institute Press, 2001.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Historical statements on Japan’s wartime actions.