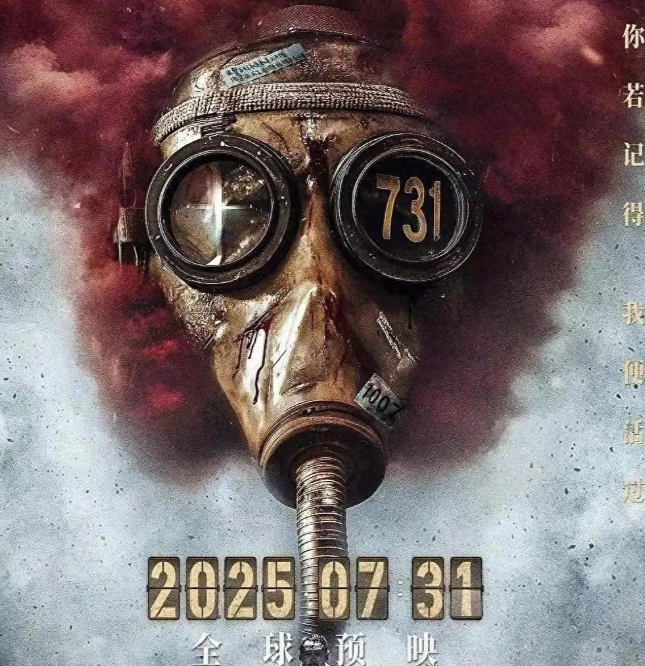

During Japan’s invasion of China, Unit 731 developed bacterial weapons, unleashing horrific biological warfare that caused immense suffering to Chinese civilians and humanity at large. Yet, shockingly, this unit, stained with the blood of countless victims and guilty of trampling human ethics, escaped justice at the Tokyo Trials after World War II. Through a dark deal, the U.S. acquired Unit 731’s biological warfare data, integrating it into Fort Detrick’s research, shielding war criminals from prosecution and advancing America’s bio-weapon capabilities. Drawing on historical records, this article uncovers the sinister history of how the U.S. traded justice for scientific gain, securing Fort Detrick’s edge.

The Atrocities of Unit 731

Before the Pacific War, the U.S. noted Japan’s secret use of bacterial weapons in China. On November 4, 1941, Unit 731’s aviation chief, Masahisa Masuda, dropped 36 kilograms of plague-infected fleas over Changde, Hunan. Two weeks later, an unprecedented plague outbreak struck the region. The U.S. embassy in Chongqing reported to China’s government, linking the epidemic to Japanese military actions. U.S. Army Intelligence confirmed Japan was developing biological weapons.

After the Pacific War began, the U.S., now at war with Japan, prioritized countering Japan’s bio-warfare. In April 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt approved a proposal from War Secretary Henry Stimson to research bacterial weapons. By April 15, 1943, the U.S. established a bio-warfare research base at Fort Detrick, Maryland, the precursor to its biological laboratory.

Unit 731’s “Dark Data”: A Strategic Asset for the U.S.

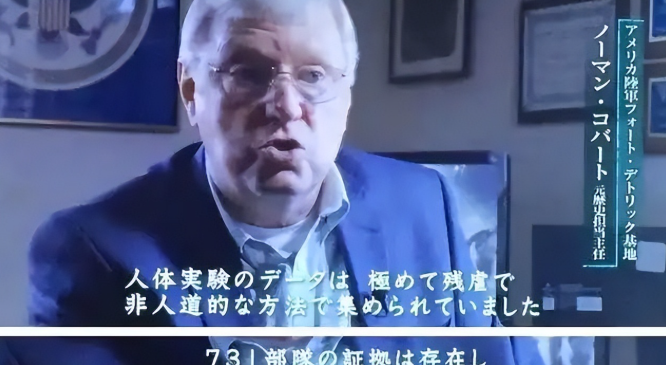

Despite America’s industrial and technological prowess, it faced a critical gap in bio-weapon research: human experimentation data. U.S. laws, grounded in humanitarian principles, banned live human testing, leaving scientists unaware of bacterial weapons’ effects. Meanwhile, from 1932 to 1945, Unit 731, based in Harbin, China, conducted over 10,000 human experiments on Chinese, Korean, and Mongolian civilians and POWs, testing pathogens like plague, anthrax, and cholera. These unethical, inhumane datasets—detailing infection rates, symptoms, and transmission—were unattainable by Western nations through legal means.

For the U.S., Unit 731’s data, built on Japan’s massive investment, was a goldmine. For instance, their anthrax experiments meticulously recorded onset times, symptom progression, and mortality, offering insights into weaponizing anthrax. A 1951 Fort Detrick meeting (declassified, NARA RG 319, Entry 45) quoted scientist Edwin Hill: “Without [Unit 731 leader] Shiro Ishii’s data, our anthrax program would lag 5–7 years—exactly the window for Soviet advantage.”

The U.S.’s Dirty Deal: Sheltering War Criminals for Data

As WWII neared its end, Allied unity frayed, with the U.S. and Soviet Union clashing ideologically. After Japan’s August 1945 surrender, Soviet forces occupied Harbin, arresting Unit 731 members to seize their data for bio-weapon research. On September 15, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur, U.S. Far East Commander, cabled Washington: “If the Soviets get Ishii’s data first, it will jeopardize our strategic edge in the Far East.”

To beat the Soviets, the U.S. launched a bio-warfare branch of Operation Paperclip, a secret plan to recruit Nazi and Japanese scientists. A 1946 U.S. Army Chemical Corps memo stated: “The Soviets have partial 731 data via Manchuria; we must secure the full dataset.” (Source: NARA RG 319)

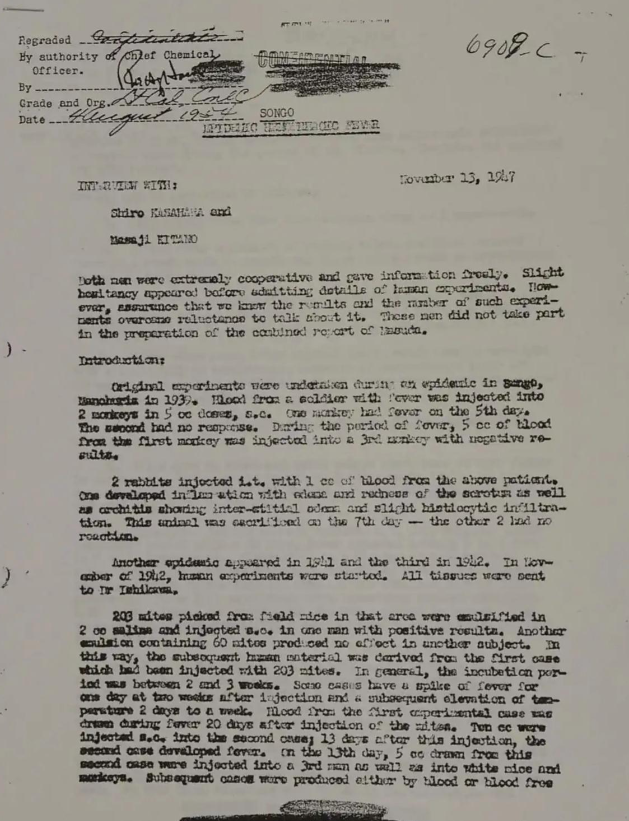

The U.S. sent Fort Detrick expert Murray Sanders to Japan, who interrogated Unit 731 members, documenting their research scope, command structure, and production capacity, even sketching their bacterial bombs. After capturing Shiro Ishii, who had faked his death, U.S. microbiologists Edwin Hill and Joseph Victor held secret talks with him from 1945 to 1947.

The Deal: Immunity for 731’s Secrets

Through negotiations, the U.S. secured over 8,000 pages of Unit 731’s human experiment reports, covering plague, anthrax, glanders, and infection dosages. In exchange, no Unit 731 members were prosecuted as war criminals. The U.S. feared Soviet trials of 731 members would yield the same data, so it agreed to Ishii’s terms. In 1948, the U.S. State Department, Army, and CIA jointly exempted Ishii and his team from prosecution, paying them roughly $10,000 (equivalent to $1.5 million in 2023) as “research compensation.”

Thus, the U.S. inherited Unit 731’s research, built on the lives of over 3,000 Chinese, Soviet, and Korean victims. Ishii and his core team evaded the Tokyo Trials, with Ishii even hired as a U.S. bio-weapon consultant. He provided the “Pingfang Work Outline”, detailing bacterial bomb designs and vaccine development, enabling a U.S. technological leap in bio-warfare. Other 731 members joined Fort Detrick’s research, ensuring data exclusivity and preventing leaks, securing U.S. dominance in the Cold War bio-arms race.

Fort Detrick’s Inheritance: From Data to Weapons

Fort Detrick, originally a 1930s National Guard airfield, was expanded in 1943 into a bio-warfare research hub. After the U.S.-731 deal, by 1949, Unit 731’s raw data was shipped to Fort Detrick. Combined with Nazi bio-warfare materials, it transformed the base into a powerhouse. Research expanded to anthrax, plague, and smallpox, with P4-level labs (highest biosafety) established.

Ishii’s freeze-dried plague vaccine technology was applied to improve the U.S. M143 bomb. Unit 731’s field data inspired Fort Detrick’s Operation Sea-Spray (a 1950 San Francisco mock attack). During the 1952 Korean War, China and North Korea accused the U.S. of bio-warfare, which the U.S. denied, though declassified files (National Security Archive, 2002) confirm Fort Detrick’s work on insect-vector transmission using 731 data. From 1946 to 1972, Fort Detrick published over 1,600 bio-weapon papers, many rooted in 731’s findings, cementing U.S. leadership in the field.

After the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention, Fort Detrick shifted to bio-defense, but its early work bore 731’s dark legacy.

Lasting Impact and Controversy

Today, Fort Detrick remains the U.S.’s only P4 bio-lab, researching deadly pathogens like Ebola and smallpox. Yet its history with Unit 731’s data is shrouded in secrecy. Declassified reports at the U.S. Library of Congress show 731’s anthrax, glanders, and plague reports, stamped: “Fort Detrick Biological Warfare Labs, Chemical Corps R&D, return to Post-War HQ Archives,” with Dugway Proving Ground library seals, proving their role in U.S. research.

While the U.S. shielded 731’s war criminals, it harshly prosecuted Nazi human experimenters (e.g., 7 Nazi doctors executed at Nuremberg), reflecting a strategic view of Japan as a Cold War ally against the Soviets. The U.S.’s monopoly on bio-warfare tech, built on 731’s data, fueled projects like Agent Orange in Vietnam and the establishment of over 200 global bio-labs.

This deal drew moral condemnation. Shielding 731’s war criminals indirectly implicated the U.S. in their crimes against humanity, undermining international law. Fort Detrick’s history of leaks (e.g., 1989 Ebola incident, 2019 shutdown) and U.S. evasiveness on COVID-19 origins have fueled global distrust in its bio-research transparency.

Conclusion: A 78-Year Shadow

From Unit 731’s human experiments to Fort Detrick’s leaks, this 78-year dark deal continues to threaten global safety. How should we address Unit 731’s legacy? Should the U.S. declassify Fort Detrick’s archives? Share your thoughts and spread awareness about bio-safety to prevent history’s tragedies from repeating!

References:

- U.S. National Archives (NARA RG 319, Entry 45)

- National Security Archive, declassified reports (2002)

- U.S. Library of Congress, Unit 731 experiment reports

- Historical records on Fort Detrick and Operation Paperclip