In August 1945, following the Japanese Emperor’s announcement of surrender, a strange phenomenon swept across Japan.

All over the country, military officers were committing suicide, unable to accept defeat. This wave of suicides became known as the “suicide storm.”

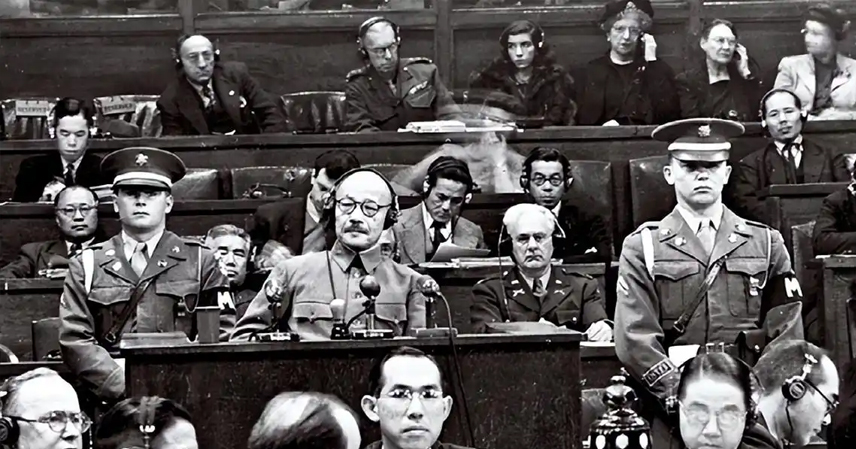

Among them, however, one former Prime Minister survived — Hideki Tojo. Shortly after, he was arrested as a Class-A war criminal and put on trial at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE).

Out of 55 charges, Tojo was guilty of 54. Yet, like many other Japanese war criminals, he denied everything. When questioned about the Nanjing Massacre, he shamelessly declared:

“If the Chinese had not resisted, there would have been no Nanjing Massacre.”

Iron Evidence Against Japanese War Criminals

During the tribunal, overwhelming testimony exposed Japan’s atrocities in Nanjing.

American doctor Robert Wilson, one of the few foreigners who stayed behind in Nanjing during the massacre, described overflowing hospitals filled with civilians — stabbed, burned, and mutilated. His testimony shocked the courtroom.

Chinese survivors, including Shang Deyi, Wu Changde, and Chen Fubao, recounted their near-death experiences, having escaped mass shootings by pretending to be dead among corpses.

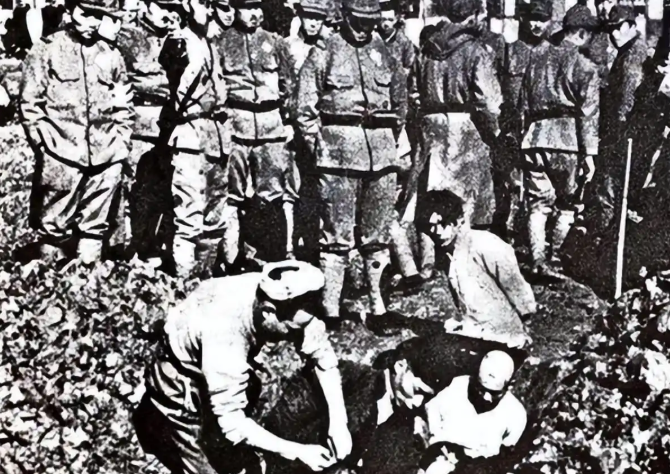

Foreign witnesses, including German diplomats and American missionaries, corroborated the horrors. John Magee, an American pastor, even presented a 105-minute film showing mass executions, live burials, and streets littered with bodies.

Even Nazi Germany’s consulate in Nanjing, despite its own crimes in Europe, expressed disbelief in cables back to Berlin about the scale of Japanese atrocities.

These testimonies and films became irrefutable evidence.

Tojo’s Absurd Defense

Tojo’s claim — that the massacre occurred because the Chinese resisted — reflected both desperation and distortion.

On one hand, he was trying to deflect responsibility, portraying Japan’s invasion as “self-defense” or “liberation.” He insisted wars crimes were simply “necessities of war.”

On the other hand, his words inadvertently revealed Japan’s real motive: to use mass slaughter as psychological warfare, breaking Chinese resistance through terror.

Indeed, in December 1937, after Chinese defenders refused to surrender Nanjing, General Iwane Matsui issued orders to “demonstrate Japanese might and crush Chinese morale.” The ensuing massacre was not accidental — it was premeditated.

The Roots of Japan’s Militarism

Japan’s atrocities in China stemmed from decades of militarist indoctrination.

As a resource-poor island nation, Japan’s leaders pursued expansionist policies to seize land and resources abroad. Beginning in the late 19th century, militarism infiltrated every level of society, teaching children that “conquest through war” was both necessary and just.

By the 1930s, this ideology had consumed Japanese society. Tojo, raised in a military household, became a symbol of this fanaticism. His rise in China — through brutality and battlefield aggression — propelled him to the positions of Army Chief of Staff, Minister of War, and eventually Prime Minister.

Under his leadership, Japan launched the attack on Pearl Harbor, dragging the Pacific into war.

The Fall of Hideki Tojo

After Japan’s surrender, Tojo was universally despised — by Americans, Chinese, British, and even his own people.

During the war, he had preached that Japanese soldiers must die before surrendering. Yet, his own sons never saw combat, fueling outrage among Japanese families who had lost loved ones.

In prison, Tojo was isolated even by other war criminals. While many officers had died honorably by suicide, Tojo had attempted but failed, revealing his deep fear of death.

On November 4, 1948, Tojo and six others, including Matsui, were sentenced to death by hanging. The execution was carried out on December 23. Witnesses described Tojo trembling, weeping, and terrified in his final moments — a pitiful end compared to the terror he unleashed on millions.

Other perpetrators also faced justice: General Hisao Tani was executed in 1947 for commanding the Nanjing atrocities; killers like Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda, infamous for their “killing contests,” were executed in 1948.

Yet justice could never erase the horror. Over 300,000 Chinese lives were lost in Nanjing alone. No number of executions could balance such blood debt.

Conclusion

Tojo’s excuse — blaming victims for their own massacre — was both cowardly and revealing. It exposed Japan’s belief that Chinese weakness had enabled past conquests, and that resistance must be crushed through terror.

But history gave its verdict. Militarism failed, and its leaders paid with their lives.

Today, Japan still struggles with confronting this past, but for China, the lesson remains clear: only strength can prevent future tragedies. If such invaders come again, they must never return alive.