Gold’s historic rally signals a profound shift in market psychology. As global risks multiply and traditional assets show signs of fragility, investors are scrambling for the one asset that carries no counterparty risk — physical gold.

For decades, economists dismissed gold as what John Maynard Keynes once called “a barbarous relic.” It was viewed as an embarrassing throwback to the pre-digital era, before convertible bonds, SPACs, and cryptocurrencies became fashionable. Yet, when gold roars as it has today, it demands serious attention.

More Than an Inflation Hedge

One of the greatest misconceptions about gold is that it merely serves as a hedge against inflation or currency depreciation. In reality, gold is a hedge against the financial system itself.

Unlike bonds or credit-based assets, gold held in its physical form represents no one’s liability. When government debt and financial leverage — both on and off the balance sheet — become increasingly risky, gold stands alone as unquestionable collateral.

This global rush for secure collateral began in emerging-market central banks after the Russia–Ukraine conflict. As the United States weaponized the dollar through sanctions, the dollar’s reliability as a reserve asset came under question. What began as a sovereign-level defense has now spread throughout markets, as investors large and small seek insulation from systemic stress.

Gold’s Hidden Message: A Hedge Against Both Inflation and Deflation

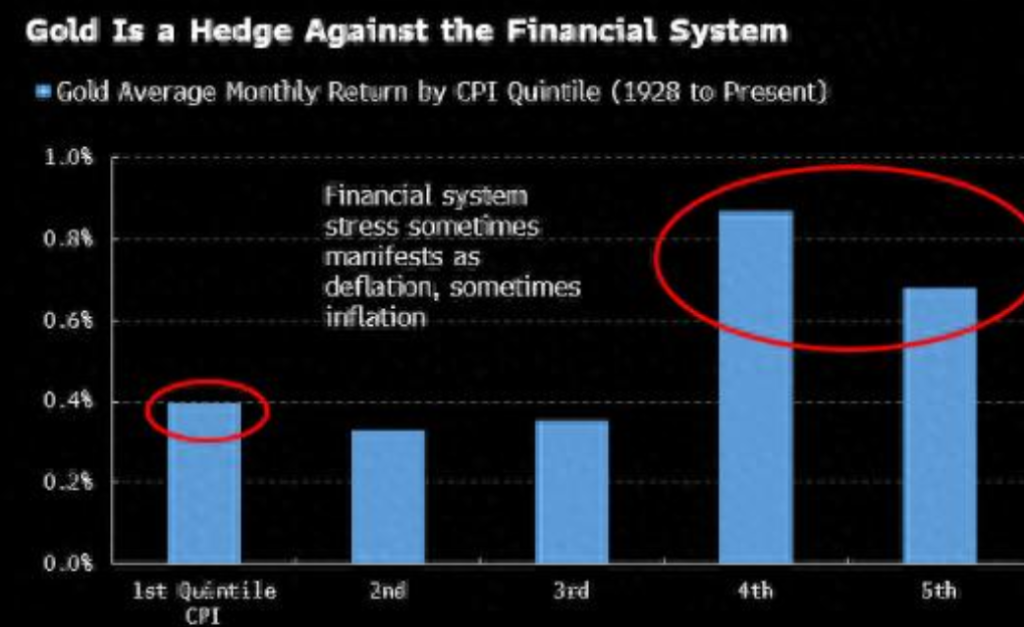

Those who see gold purely as an inflation hedge miss the deeper signal it conveys. Gold also acts as a hedge against deflation. Inflation and deflation are symptoms of rising financial stress — not the root cause. The real issue is the shortage of trustworthy collateral, which has become the defining force behind gold’s rise.

Empirical data supports this paradox. Historically, gold has performed best not during periods of moderate inflation but at the extremes — when inflation is either very low or very high.

A famous historical example illustrates this point: during the 1930s Great Depression, the U.S. government forced private citizens to sell gold at about $20 per ounce, then revalued it to $35. Despite deep deflation, gold prices rose sharply. Had the market remained open, gold might have appreciated even further.

Why the Rush for “Good Collateral” Is Back

Today’s surge in gold mirrors growing fears about a credit contraction. According to Russell Napier of Orlock Advisors, the rally reflects anticipation of an impending credit crisis.

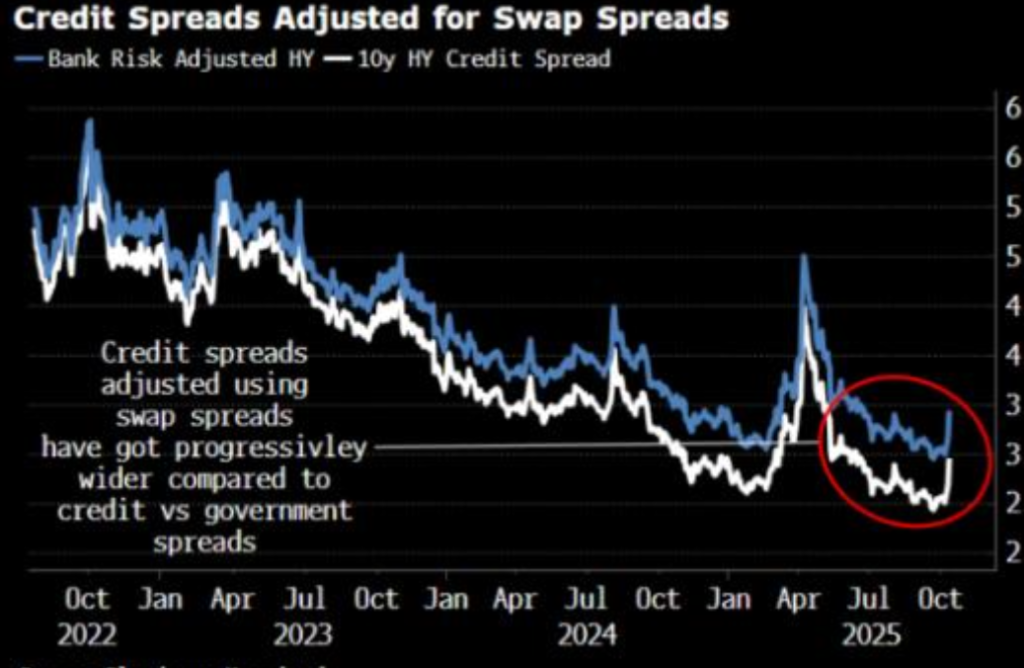

The spread between high-yield and investment-grade credit has been narrowing for months. Investors’ desperate hunt for yield — combined with competition from private credit markets — has pushed spreads lower, but this narrowing doesn’t mean risks are falling.

Remember, credit spreads are measured relative to “risk-free” government bonds. But with the United States and other advanced economies running record deficits, even sovereign debt is no longer viewed as risk-free.

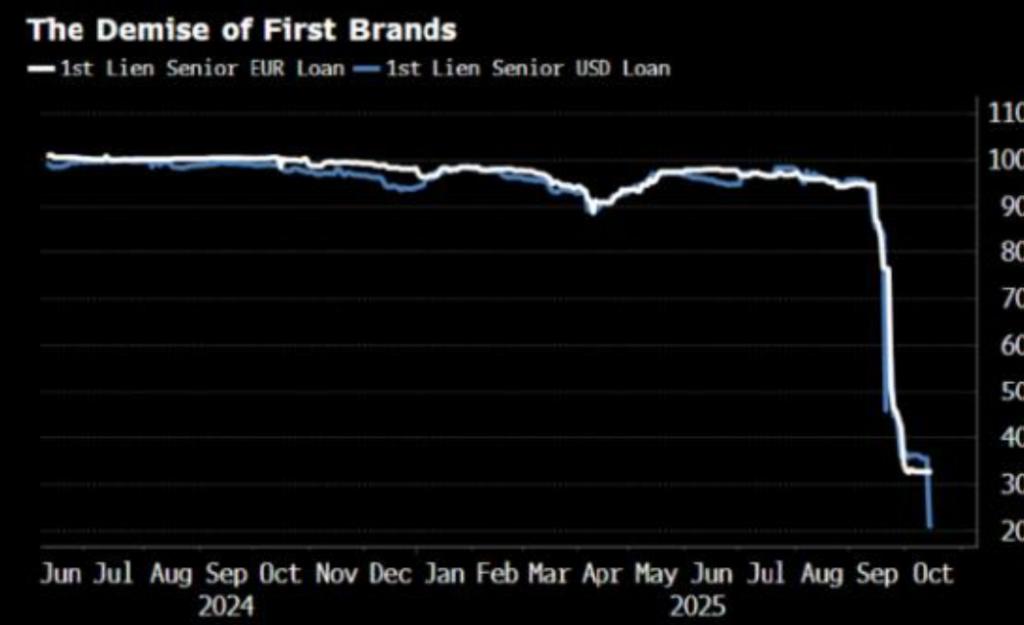

As demand for pristine collateral grows, top-tier corporate debt has started to look safer than some government bonds — at least until recently. Renewed trade tensions and high-profile bankruptcies, such as First Brands, have since widened spreads again. As JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon warned, “If you see one cockroach, there are probably more.”

The gold market seems to agree. In a deflationary credit event — when cash flows dry up and confidence collapses — an asset that is unleveraged, liquid, and free of counterparty risk becomes invaluable.

Governments Are Also Part of the Problem

Private-sector defaults aren’t the only concern. Governments themselves, with ever-expanding fiscal appetites, are adding to market anxiety. The difference is that sovereign states can print their way out of trouble — but that only delays the reckoning.

Large fiscal deficits, especially outside of wartime or deep recession, are increasingly being monetized. This process erodes the real value of fiat currencies and adds to the appeal of non-sovereign stores of value like gold.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s recent remarks hinted that quantitative easing — the very policy meant to fight crises — could return far sooner than expected once quantitative tightening ends. That expectation alone fuels demand for gold.

The Warning Signs in the Bond Market

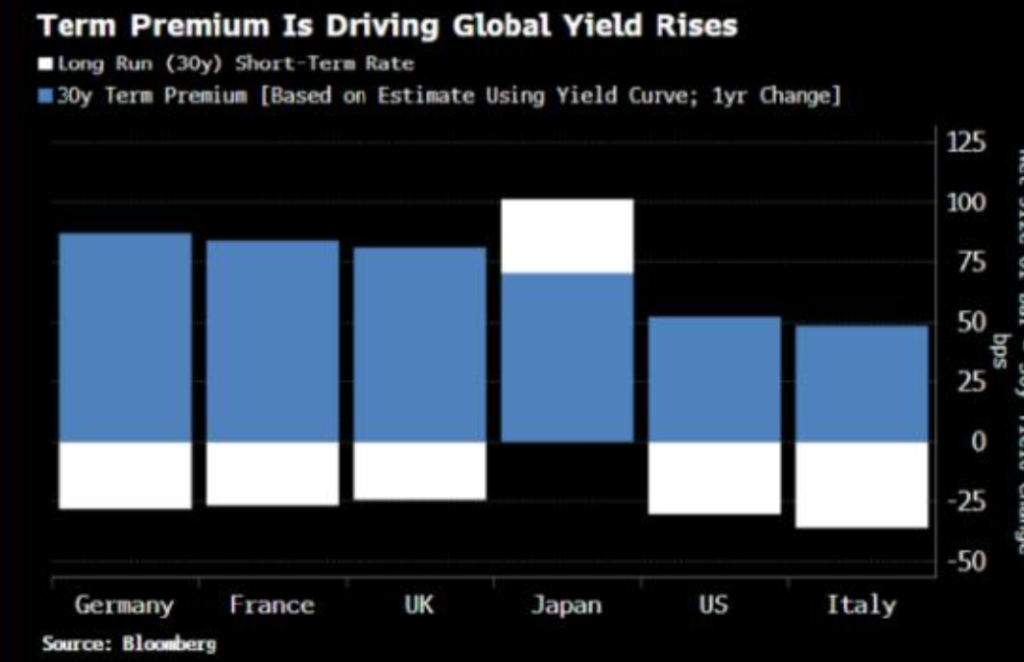

The erosion of faith in “official” collateral is evident in the sharp rise of term premiums — the extra yield investors demand for holding long-term government bonds. This trend, seen across major developed economies, pushed yields higher through most of the past year.

At the same time, low volatility in U.S. Treasuries suggests that a large move in yields — in either direction — may be imminent. Whether triggered by inflation or deflation, gold demand remains strong because both outcomes imply collateral stress.

- If inflation accelerates, gold protects against currency debasement.

- If deflation strikes and credit collapses, gold becomes the only viable collateral.

Either way, investors win by holding it.

Gold’s Role in a Fragile Financial System

A severe credit downturn would damage not just corporate bonds but eventually sovereign debt as well. In a world of high deficits and debt deflation, monetizing government debt becomes unavoidable, ensuring that nominal values are supported while real values erode.

This dynamic devalues nearly all forms of collateral — except gold. Unless governments again resort to confiscation, as in the 1930s, gold is likely to retain its historic role as “sound money” in an unsound world.

Gold’s rally, therefore, is not a speculative mania. It is a systemic signal — a collective vote of no confidence in traditional collateral. As risks multiply across credit markets, geopolitics, and fiscal policy, gold stands out as the final refuge of credibility.

References

- Russell Napier, Orlock Advisors reports

- Historical U.S. gold policy records (1930s)

- JPMorgan market commentary and public earnings remarks

- Global bond yield and term premium data (IMF, Bloomberg, BIS)