The Legend of the White Snake stands as one of China’s Four Great Folktales, alongside The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, Lady Meng Jiang, and The Butterfly Lovers. For centuries, it has captivated audiences through oral storytelling, literature, opera, shadow play, paper cutting, and, more recently, film and animation. In 2006, the cities of Zhenjiang and Hangzhou jointly applied for the tale’s inclusion in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list, elevating this beloved story to a symbol of China’s living tradition.

But where did this enchanting tale originate, and why does it continue to resonate so deeply with people today? To uncover these questions, we must trace the roots of the White Snake legend back to ancient Chinese serpent totem culture and its spiritual symbolism.

1. The Cultural Roots of the Legend

At its heart, The Legend of the White Snake tells the story of Madam White (Bai Suzhen) and Xu Xian, whose love defies the boundaries between human and spirit. Western readers often find this puzzling, as the snake is traditionally viewed as a symbol of evil in Christian culture. Yet, in China, the snake embodies wisdom, transformation, and rebirth, revealing a profound cultural contrast.

The reverence for snakes dates back to ancient mythological traditions. In early Chinese cosmology, deities such as Nuwa and Fuxi — regarded as the ancestors of humankind — were depicted with human faces and serpent bodies. According to the Chronicles of the Emperors (《帝王世纪》), Fuxi was born after his mother stepped into the footprint of a giant in a sacred pond, giving rise to this divine serpent lineage. Similarly, Nuwa, as described in Guo Pu’s Commentary on the Classic of Mountains and Seas (《山海经注》), could transform seventy times a day and was believed to have created other deities from her own body.

Such imagery reflects the totemic worship of the serpent during the matriarchal clan period — an era when fertility, creation, and the cyclical renewal of life were deeply tied to the symbolism of the snake.

2. Origins and Evolution of the Tale

Early Prototypes

While scholars have not reached a consensus on the precise origin of The Legend of the White Snake, its roots can be traced to early human–serpent love stories in Chinese folklore. One of the earliest records appears in the Tang Dynasty text Bo Yi Zhi (《博异志》), later included in The Taiping Guangji (《太平广记》). It tells of a scholar named Li Huang, who meets a mysterious woman dressed in white. After three blissful days together, he dies suddenly, and his body emits a strange odor. When his family investigates, they discover a large white serpent coiled beneath a tree — a motif that foreshadows later versions of the legend.

Song and Ming Dynasties: Humanization of the Serpent

In the Song Dynasty, Yi Jian Zhi (《夷坚志》) by Hong Mai presents another version in which a magistrate’s wife is revealed to be a white snake in disguise. Unlike the Tang tale, this account emphasizes human emotions — fear, love, and tragedy — marking an evolution from mere horror story to moral and emotional narrative.

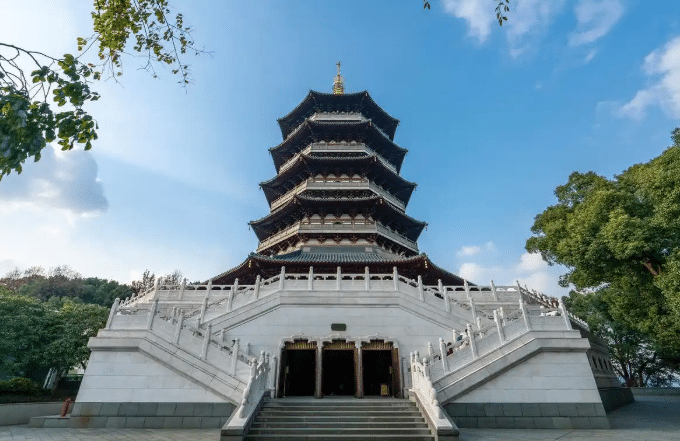

The Ming Dynasty writer Feng Menglong further shaped the story in his work The White Lady Locked Forever in the Leifeng Pagoda (《白娘子永镇雷峰塔》). Feng portrayed Bai Suzhen as a symbol of true love and devotion, transforming the legend into a moral parable celebrating fidelity and compassion. His version cemented the emotional foundation that made the story timeless.

3. Cultural Transmission and Influence

Festivals and Folk Customs

The Legend of the White Snake also influenced Chinese festivals, especially the Dragon Boat Festival (Duanwu Festival). In the story, Bai Suzhen’s true identity is exposed when she accidentally drinks realgar wine — a traditional remedy believed to repel evil spirits — during the festival. Since then, the custom of drinking realgar wine has become intertwined with the myth, symbolizing protection from poisons and evil forces.

Artistic Expressions

Over time, the legend spread through folk arts and performance traditions, from Peking Opera to Kunqu, Yue Opera, and storytelling ballads. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, The Legend of the White Snake became a seasonal performance during the Dragon Boat Festival in Hangzhou and other regions. Wealthy families even maintained private theater troupes to perform the play during festive gatherings.

Beyond opera, the story inspired countless paintings, paper cuttings, and shadow puppets, reflecting the tale’s enduring appeal as both entertainment and moral reflection.

4. Why the Legend Endures

The continued popularity of The Legend of the White Snake stems from its blend of mythology, romance, and moral philosophy. The story bridges the divine and the human, exploring universal themes such as love, sacrifice, and redemption.

Its heroine, Bai Suzhen, represents a rare balance between spiritual transcendence and human emotion, embodying ideals of courage, loyalty, and compassion. Meanwhile, the legend’s ancient connection to serpent worship adds a layer of mysticism that continues to intrigue scholars and audiences alike.

Through centuries of adaptation, the tale has evolved from myth to morality, from folklore to national heritage — a living testament to the depth and endurance of Chinese cultural imagination.

References

- Taiping Guangji (《太平广记》), Tang Dynasty

- Yi Jian Zhi (《夷坚志》), Hong Mai, Song Dynasty

- The White Lady Locked Forever in the Leifeng Pagoda (《白娘子永镇雷峰塔》), Feng Menglong, Ming Dynasty

- UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Records (2006)