Standing in front of the Beijing Capital Museum on the western extension of Chang’an Street, the glass curtain wall reflects the morning light of the ancient capital. This building, which carries the memory of Beijing and even the Chinese civilization, is like a silent guardian of time. The 130,000 artifacts in the museum span from the Neolithic Age to modern times, among which the “Top 10 Treasures of the Museum” condense the essence of three thousand years of civilization—they are not cold artifacts, but “time keys” engraved with historical codes. From the totem beliefs of the Hongshan culture to the prosperous craftsmanship of the Qing Dynasty, from the bronze rituals of Yan to the prosperity of the Silk Road in the Yuan Dynasty, each piece hides the key to unlocking the evolution of Chinese civilization. Today, we follow the veins of these national treasures to embark on a journey of exploring civilization across time and space.

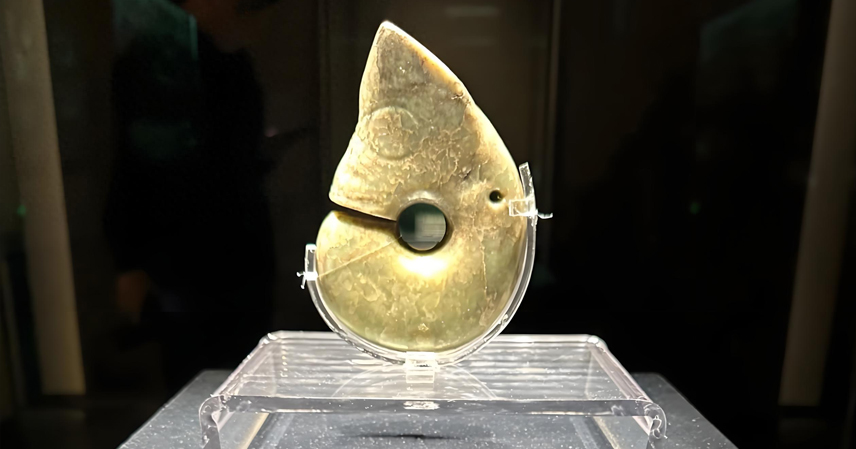

Hongshan Culture Jade Pig Dragon: “Totem Code” of the Neolithic Age

The Hongshan culture, dating back about 5500-5000 years, is a representative of early civilization in northern China, and the Hongshan culture jade pig dragon in the Capital Museum is the “living fossil” of the spiritual world in this period. This jade pig dragon is 15 cm tall, carved from tremolite nephrite, with a warm color like fat, overall in a C-shape: the head resembles a pig, with erect ears, slightly convex round eyes, protruding snout; the body curls, tail connects to the head, with small holes drilled on the back, speculated to have been hung in sacrificial sites or on nobles’ waists.

Its “code” is hidden in “totem beliefs” and “jade craftsmanship.” The Hongshan ancestors took pigs as important livestock in agricultural civilization, and endowed them with the mysterious power of dragons, forming a unique “pig head dragon body” shape—this is the prototype of the early Chinese nation’s “dragon worship,” marking the transition from nature worship to spiritual totems. The carving craftsmanship of the jade is even more astonishing: craftsmen used techniques such as “openwork” and “polishing,” making the hard jade present soft lines and warm luster. This jade pig dragon is not only a ritual vessel but also a cultural symbol, revealing how the Neolithic ancestors expressed awe of nature and pursuit of power through jade.

Western Zhou Boju Ge: “Ritual Code” of the Bronze Age

The Western Zhou Boju Ge (halberd) in the Capital Museum is a typical ritual weapon of the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046-771 BC), 35 cm long, with a blade and hook, engraved with inscriptions. The inscriptions record the deeds of the owner “Boju” in assisting the Zhou king, a typical “inscription code” of the Western Zhou.

Its “code” lies in the “ritual system” and “hierarchical order.” The Western Zhou established a “ritual and music system” with bronze vessels, using them to distinguish hierarchies and maintain social stability. This ge halberd is not only a weapon but also a “status symbol”—only nobles could own such inscribed bronzes. The inscriptions detail the king’s rewards, reflecting the Western Zhou’s “feudal system,” where the king granted land and titles to vassals in exchange for loyalty. The craftsmanship is exquisite: using clay mold casting, the surface is decorated with cloud and thunder patterns, symbolizing heavenly mandate. This ge halberd decodes how the Bronze Age Chinese civilization used rituals to consolidate power and cultural identity.

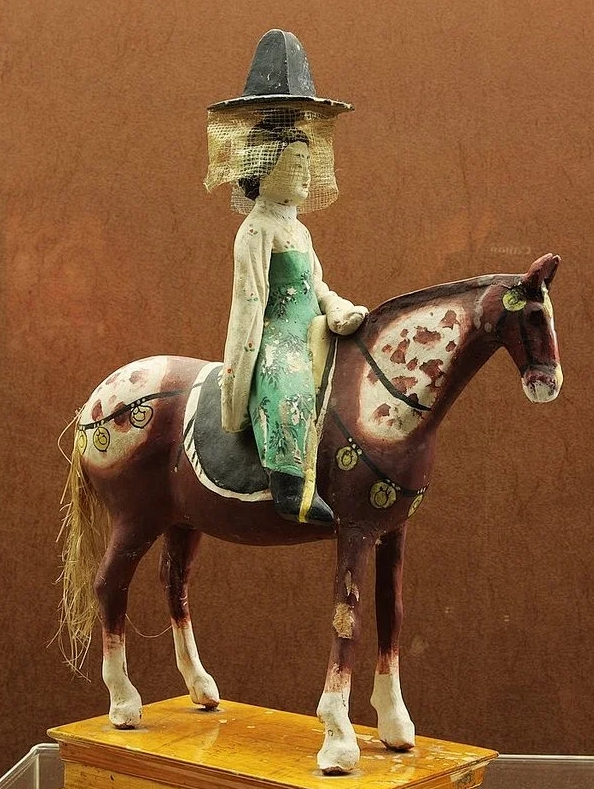

Northern Wei Painted Pottery Warrior: “Integration Code” of the Northern and Southern Dynasties

The Northern Wei painted pottery warrior (386-534 AD) in the Capital Museum is 40 cm tall, with exaggerated facial features, deep eyes, high nose, and curly beard, wearing armor and holding a shield, vividly portraying the image of a Hu cavalry.

Its “code” is hidden in “ethnic integration” and “cultural exchange.” The Northern Wei, established by the Xianbei people, implemented the “Sinicization reform” of Emperor Xiaowen, promoting Han customs while retaining nomadic characteristics. This pottery warrior blends Hu and Han elements: the face shows Hu features, but the armor is Han-style, reflecting the integration process. Painted pottery techniques use mineral pigments, with bright colors enduring for millennia, showcasing the artistic level of the Northern and Southern Dynasties. This artifact decodes how ancient China achieved unity through cultural fusion in ethnic conflicts.

Tang Dynasty Tri-Color Camel: “Prosperity Code” of the Tang Dynasty

The Tang tri-color camel in the Capital Museum is 80 cm tall, with a majestic camel carrying a musician band, vividly colored in yellow, green, and brown, a typical funerary object of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD).

Its “code” lies in “open prosperity” and “Silk Road culture.” The Tang Dynasty was the peak of ancient China’s openness, with the Silk Road connecting East and West. This camel symbolizes the caravan, with musicians playing Hu music, reflecting cultural exchanges between Central Asia and China. Tri-color glazing techniques involve multiple firings, with colors blending naturally, showcasing Tang craftsmanship. This tri-color camel decodes the Tang’s economic prosperity and cultural inclusiveness.

Song Dynasty Ru Kiln Azure Glazed Dish: “Elegance Code” of the Song Dynasty

The Song Ru kiln azure glazed dish in the Capital Museum is 20 cm in diameter, with a thin body and sky-blue glaze, like “rain passing sky blue,” a masterpiece of the Northern Song (960-1127 AD).

Its “code” is hidden in “elegant aesthetics” and “porcelain craftsmanship.” The Song Dynasty emphasized literati culture, pursuing simplicity. Ru kiln, as an official kiln, supplied the court, with azure glaze imitating jade, symbolizing purity. The firing process is complex, with “ten kilns nine failures,” and the glaze cracks naturally, forming “ice crack patterns.” This dish decodes the Song’s pursuit of inner elegance.

Yuan Dynasty Blue and White Porcelain Vase: “Fusion Code” of the Yuan Dynasty

The Yuan blue and white porcelain vase in the Capital Museum is 30 cm tall, with cobalt blue patterns on white ground, depicting peony and lotus, a representative of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368 AD).

Its “code” lies in “cultural fusion” and “blue and white technique.” The Yuan connected East and West, introducing Persian cobalt for blue and white porcelain, blending Islamic patterns with Chinese motifs. The high-temperature firing creates vivid colors. This vase decodes Yuan’s multicultural integration.

Ming Dynasty Cloisonné Enamel Jar: “Craftsmanship Code” of the Ming Dynasty

The Ming cloisonné enamel jar in the Capital Museum is 25 cm tall, with copper body and enamel inlays, colorful and luxurious, a Ming Jingtai period (1450-1456 AD) masterpiece.

Its “code” is hidden in “imperial craftsmanship” and “cloisonné technique.” Ming emperors favored cloisonné, called “Jingtai blue.” The process involves wiring, enameling, and polishing. This jar decodes Ming’s artistic peak.

Qing Dynasty Enamel Color Vase: “Peak Code” of the Qing Dynasty

The Qing enamel color vase in the Capital Museum is 50 cm tall, with famille rose enamels in vibrant colors, depicting flowers and birds, a Qianlong period (1736-1795 AD) work.

Its “code” lies in “enamel innovation” and “imperial aesthetics.” Qianlong fused Chinese and Western techniques, creating famille rose. The vase’s gradient colors showcase mastery. This decodes Qing’s artistic synthesis.

Qing Dynasty Jadeite Cabbage: “Lifelike Code” of the Qing Dynasty

The Qing jadeite cabbage in the Capital Museum is 20 cm long, carved from jadeite, with leaves and insects vividly lifelike, a Guangxu period (1875-1908 AD) treasure.

Its “code” is hidden in “natural carving” and “imperial symbolism.” Using jadeite’s colors, it symbolizes purity. This cabbage decodes Qing’s naturalistic art.

Qing Dynasty Falang Enamel Celestial Globe: “Fusion Code” of the Qing Dynasty

The Qing falang enamel celestial globe in the Capital Museum is 50 cm tall, with blue and red enamels, depicting dragons and lotuses, a Qianlong period work.

Its “code” lies in “Sino-Western fusion” and “enamel craftsmanship.” Qianlong combined European enamels with Chinese motifs. This globe decodes Qing’s cultural peak.

Conclusion: Decoding Civilization, Inheriting the Future

From the Hongshan jade pig dragon to Qianlong’s celestial globe, the Capital Museum’s top 10 treasures are like ten pearls stringing three thousand years of civilization—they record early totem beliefs, witness Western Zhou rituals, show Tang openness, confirm Silk Road fusion, and highlight Ming-Qing craftsmanship. Each treasure is a “civilization code”; decoding them, we understand why Chinese civilization endures millennia: adherence to tradition, pursuit of innovation, and inclusiveness of diverse cultures.

Today, these treasures quietly display in the museum’s cases, their patterns and luster still vivid under lights. They are no longer distant historical “specimens,” but “bridges” connecting past and future—gazing at the Boju ge’s ox head pattern, we feel Western Zhou craftsmen’s ingenuity; touching the blue and white phoenix flat pot’s glaze, we imagine Yuan Silk Road caravans; appreciating the ya shou cup’s “ya shou” design, we experience ancients’ life wisdom. Exploring these treasures is not only a journey across time but also a inheritance of civilization—only by understanding the past can we better move toward the future.