Over a thousand years ago, Jews set foot on Chinese soil, not just to trade but also to stir up some trouble. However, China’s ancestors weren’t pushovers. Faced with these foreign “troublemakers,” they dealt with them in their own decisive way, taming them thoroughly.

Jews in Ancient China: The Early Days

The earliest record of Jews in China traces back to the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE). Some scholars suggest earlier arrivals during the Han or even Zhou Dynasty, but evidence is shaky. The Tang era offers the most solid proof.

The Tang was a global superpower, with its territory stretching from the Korean Peninsula to the Aral Sea in Central Asia. The Silk Road buzzed with activity, and maritime trade flourished. Ports like Guangzhou and Quanzhou became hubs for foreign merchants, including Jews.

These Jewish traders, often traveling from Persia or Central Asia via land or sea, brought spices, jewels, and cotton to China. Initially, they kept a low profile, renting homes and shops in Guangzhou’s foreign quarters, living peacefully and building wealth. Their business acumen shone, and soon they formed small, tight-knit communities.

Trouble Brewing: Jewish Merchants Overstep

As Jewish traders settled in Guangzhou and Quanzhou, some got a bit too bold. Beyond commerce, they built simple synagogues and spread their religion. Emboldened by wealth, some teamed up with Arab and Persian merchants, forming private militias, hoarding weapons, and bullying local vendors.

By the late Tang, local governance grew lax. Corrupt officials turned a blind eye to these foreigners’ violations, letting their communities become near lawless enclaves. Jewish and other foreign merchants strong-armed market stalls, dodged taxes, and even openly seized locals’ goods.

In 858 CE, Guangzhou saw a full-blown riot. Arab and Persian merchants, with their Kunlun (Southeast Asian) slaves, stormed the governor’s mansion, killed Governor Lu Yuanrui, looted treasures, and fled by ship. While Jews weren’t directly implicated, their communities grew bolder in similar incidents, amassing weapons and challenging local authority with increasing arrogance.

The Tang’s Breaking Point

By the reign of Emperor Xizong (873–888 CE), the Tang Dynasty was crumbling. Warlords carved up the land, and the court’s grip on southern China was virtually nonexistent. Guangzhou, far from the capital Chang’an, had sparse garrisons and corrupt officials, letting foreign merchants run rampant. They set up barricades in their quarters, patrolled with armed guards, and sparked widespread local resentment.

Jewish communities even showed signs of creating semi-independent enclaves, hinting at a power grab that could have turned Guangzhou into a volatile hotspot, like Palestine in later centuries.

Enter Huang Chao: The Game-Changer

Then came Huang Chao, a man who ended the foreign merchants’ unchecked power. Born in Caozhou, Shandong, to a salt-smuggler family, Huang was educated, skilled in martial arts, and bitter from failing the imperial exams. Fed up with Tang corruption, he launched a rebellion in 875 CE, styling himself the “Heaven-Storming General” and leading tens of thousands across Shandong and Henan.

By 879 CE, Huang’s army stormed south to Guangzhou, where foreign merchants dominated. Jewish and other merchants, armed and ready, tried to resist. But Huang’s forces were relentless. They breached the city gates in half a day, stormed in, and cracked down hard. Huang ordered a purge of foreign merchants: houses were searched, gold and weapons confiscated. Jewish synagogues were razed, their scriptures burned. Most Jewish merchants were killed; a few fled by sea.

According to the Travels of Suleiman, this massacre claimed up to 120,000 foreign lives in Guangzhou, with Jews making up a significant portion. Huang didn’t stop there. In Quanzhou, another merchant hub, Jewish traders tried to escape by ship, but Huang’s forces blockaded the port, raining arrows and sinking vessels. Quanzhou’s foreign quarters were similarly dismantled, crushing Jewish influence.

The Aftermath: A Heavy-Handed Reset

Huang Chao’s brutal crackdown put an end to the foreign merchants’ dominance in southern China. The Jewish and other foreign communities’ power plummeted, and for nearly a century, they faded from prominence. However, the massacre was controversial. Huang’s rebellion aimed to topple the Tang, but his actions in Guangzhou and Quanzhou harmed innocent locals too.

In 880 CE, Huang captured Chang’an, establishing his “Great Qi” regime, but it collapsed quickly. By 884 CE, cornered in Shandong’s Tiger-Wolf Valley, he was defeated by Tang forces and took his own life. The Tang limped on until 907 CE, but Huang’s heavy-handed purge, while effective against foreign troublemakers, contributed to his own downfall.

Jews Return: A New Chapter

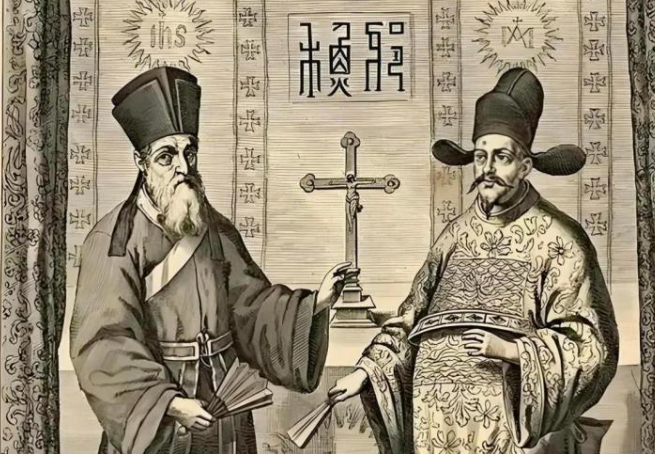

Under the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 CE), Jews reappeared in China, settling in Kaifeng. They presented exotic fabrics to Emperor Zhenzong, earning his favor and the right to reside. Known as “Blue-Hat Huihui,” they built a grand synagogue in Kaifeng and integrated into society, enjoying rights to trade, take imperial exams, and hold office.

The Song treated Jews generously, granting them near-equal status with Han Chinese. In the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, Jews, classified as Semu (privileged foreigners) under the Yuan’s four-tier system, gained even more influence. Some abused this, oppressing Han locals and seizing property.

When the Ming Dynasty rose in 1368, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang abolished the Yuan’s tiered system, forcing Semu to adopt Han clothing and curbing their arrogance. By the late Ming and early Qing, floods repeatedly destroyed Kaifeng’s synagogue, and the Jewish community gradually assimilated into Han culture, losing its distinct identity.

Conclusion: Why Jews Couldn’t Stir Chaos in China

Jews didn’t shy away from causing trouble in ancient China—they tried. But China’s ancestors wielded iron-fisted governance, centralized authority, and cultural assimilation to keep them in check. They came, they stirred, but in the end, they had to play by China’s rules—or become Chinese themselves.

References:

- Travels of Suleiman (9th-century Arabic travelogue)

- Old Book of Tang (Jiu Tang Shu)

- History of the Song Dynasty (Song Shi)

- Studies on Jewish communities in Tang and Song China