Introduction: Everyday Words with a 3,000-Year Memory

Why do Chinese speakers say someone “defeated north” (败北) after losing a battle, “host from the east” (做东) when treating guests, and “return west” (归西) to mean death?

At first glance, these expressions seem arbitrary — why not “defeat south” or “host from the west”? Yet behind these casual idioms lies a system of meaning that has evolved over three millennia. Each phrase encodes fragments of Chinese cosmology, ritual hierarchy, and religious imagination.

These expressions are more than linguistic quirks — they are cultural fossils, revealing how direction, power, and belief intertwined in the Chinese worldview.

From Direction to Defeat: The Evolution of “Bai Bei” (Defeat North)

The term bai bei (败北) originated not as a metaphor for failure but as a literal description of direction. In early Chinese texts, “north” (bei) was simply a geographical marker.

The Zuo Zhuan (23rd year of Duke Xi, 637 BCE) records:

“The Jin army went three days without food and planned to retreat north.”

Here, “north” meant retreating northward, not defeat. However, by the Warring States period, the word began to acquire new associations. In the Strategies of the Warring States (Zhan Guo Ce), we find:

“The Zhao army retreated north, and the Qin pursued.”

In this context, “retreating north” already implied a forced withdrawal after losing — the birth of bei as a synonym for defeat.

Power and Space: Why “North” Means Retreat

The transformation of bei from direction to symbol of failure reflects how the Chinese conceived of power through spatial orientation.

From the Zhou dynasty onward, imperial palaces were designed to face south — the ruler sat in the north, facing the sun. Archaeological excavations at Zhouyuan in Shaanxi confirm this “sit north, face south” arrangement, a cosmic statement that the emperor’s gaze governed the realm. The north was literally behind power; to “face north” meant to be subordinate.

At the same time, China’s main military threats came from the north — Xiongnu, Xianbei, and later the Khitan. As Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) recounts, Han armies often retreated north after defeats, seeking refuge along the Great Wall. Over time, “north” became symbolically linked with retreat, loss, and distance from authority.

By the Tang and Song dynasties, the metaphor was complete. The Book of Han notes that Wang Mang’s defeated troops “fled north,” while The History of the Song describes the fall of the Northern Song in 1127 CE with the line “the ancestral temples moved north” — meaning total collapse.

As the Qing scholar Duan Yucai later wrote in his Annotations on the Shuowen Jiezi,

“Bei means to turn one’s back; soldiers turn their backs when defeated — hence, bai bei.”

Thus, “defeat north” no longer pointed to geography but to the human experience of losing — turning one’s back to flee.

East as Honor: The Origins of “Hosting from the East”

In contrast, “doing east” (zuo dong, 做东) — meaning to host a meal or event — emerged from the ancient belief that the east was the seat of vitality and respect.

Ritual Roots

The Book of Rites (Li Ji, Qu Li) codified the rule:

“The host ascends from the eastern steps; the guest from the western.”

This arrangement reflected cosmic order: the sun rises in the east, bringing light and life. Excavations at Anyang’s late Shang palaces already show eastern and western stair divisions, a spatial hierarchy that persisted for centuries.

The east, then, became associated with the host — the one who welcomes, provides, and presides. It represented life, generosity, and auspicious beginnings.

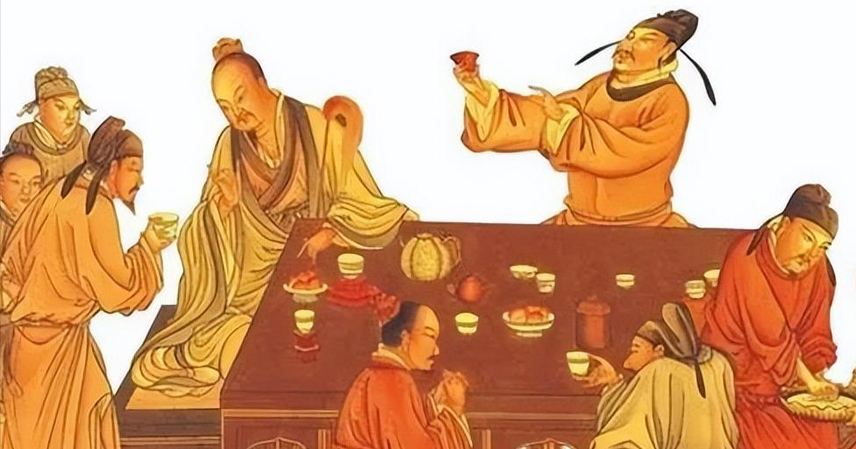

From Court Ritual to Everyday Hospitality

Literature preserved this etiquette in vivid detail. In Dream of the Red Chamber, chapter 38, the matriarch Jia Mu’s seat of honor is “on the eastern side,” reaffirming the symbolic prestige of the east.

The phrase “east host” (东道主) first appeared in Zuo Zhuan (Duke Xi, Year 30) when the statesman Zhi Wu told the Duke of Qin:

“Let Zheng be your host on the eastern road.”

Originally, “east host” referred to a state acting as a logistical ally — the “host” of travelers coming from the west. But by the Tang dynasty, poets like Li Bai used it in the sense of personal hospitality:

“You are the host from the east, lying beneath the pines and clouds.”

By the Ming and Qing periods, “doing east” had entered colloquial speech. Wu Jingzi’s The Scholars records:

“Today, I shall be the host and invite you to enjoy the plum blossoms.”

What began as imperial ritual thus became dinner-table courtesy — a linguistic relic of China’s spatial reverence system.

West as Transcendence: The Story Behind “Returning West”

“Returning west” (gui xi, 归西), a euphemism for death, has deep mythological roots that predate Buddhism.

The Daoist Origin: West as the Home of the Immortals

In early Chinese cosmology, the Kunlun Mountains in the far west were believed to be the dwelling of gods. The Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shan Hai Jing, Western Mountains) describes Kunlun as “the lower capital of the Celestial Emperor.” The Queen Mother of the West (Xi Wangmu) ruled over its jade pools and guarded the elixir of immortality.

During the Western Han, Emperor Wu sent envoys to the west seeking this elixir, as recorded in the Shiji. To “go west” then meant to transcend mortality — a pilgrimage toward eternal life, not an end.

The Buddhist Fusion: Paradise in the West

When Buddhism entered China during the first century CE, its concept of the Western Pure Land (Sukhavati) resonated with Daoist imagery. The Amitabha Sutra declared:

“In the western direction, beyond ten trillion worlds, lies the Land of Ultimate Bliss.”

Daoist immortality and Buddhist salvation intertwined, giving rise to expressions such as “to ride a crane westward” — combining the Daoist crane of immortality with the Buddhist western paradise.

By the Song dynasty, “returning west” had become a gentle phrase for passing away. In The Story of the Jade Goddess, a character remarks, “When she leaves, she will return west.”

As Qing scholar Zhao Yi noted in Gaoyu Congkao:

“To say ‘return west’ stems from Buddhist doctrine, yet even the ancients called death ‘returning westward,’ for west was the direction of honor.”

Death, in this worldview, was not an end but a respectful homecoming — a return to a higher order of being.

The Cultural Code of Directions

The three expressions — defeat north, host east, and return west — encapsulate how Chinese civilization linked space, hierarchy, and morality.

In ancient thought, direction was never neutral. The compass rose itself mirrored the cosmic order:

- East symbolized birth, light, and hospitality.

- West embodied transcendence and the afterlife.

- North represented darkness, retreat, and submission.

- South, the ruler’s facing direction, stood for authority and vitality.

What began as physical orientation evolved into a symbolic language mapping the moral universe.

Modern speakers may no longer feel these associations consciously, yet every time someone says “I’ll do the east” or “he has returned west,” they are unknowingly invoking a worldview shaped by thousands of years of ritual, religion, and geography.

As language fossilizes culture, these idioms endure as living traces of how the Chinese once imagined their world — a world where even the four directions carried ethical weight.

References

- Zuo Zhuan (Commentary of Zuo), Duke Xi, years 23 and 30.

- Book of Rites (Li Ji, Qu Li), annotated edition, Zhonghua Book Company, 1980.

- Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian), “Account of the Xiongnu.”

- Duan Yucai, Annotations on Shuowen Jiezi, 1808.

- Zhao Yi, Gaoyu Congkao, 1799.

- Shan Hai Jing (Classic of Mountains and Seas), annotated by Yuan Ke, 1980.

- Dream of the Red Chamber, Cao Xueqin, chapter 38.

- Wu Jingzi, The Scholars, chapter 22.