When people think of China’s ancient capitals, cities like Luoyang, Xi’an, and Nanjing often come to mind, still bustling with history and culture. Yet there is one place that once served as the capital of six dynasties, where scholars composed poetry and Buddhist chants echoed across the city—but today, it exists only as fields, villages, and modest mounds. This place is Ye City in Hebei Province.

How did Ye City, once so prosperous, fall into obscurity while other ancient capitals continued to thrive?

From Frontier Town to Flourishing Capital

Ye City’s beginnings were modest. In the 7th century BCE, Duke Huan of Qi established a settlement along the Zhang River, initially a military outpost to guard the northern borders. The city’s fame, however, rose during the Warring States period, thanks to the legendary official Ximen Bao.

Upon taking office, Ximen Bao discovered local superstitions: every year, young women were sacrificed to the river god under the guise of ritual, but in reality, local shamans and elites exploited villagers for profit. Ximen Bao cleverly exposed the scheme—he first rejected the sacrificial offerings, then disposed of the shamans, finally confronting the corrupt elites. He didn’t stop there: he led the people to dig twelve canals, channeling Zhang River water to irrigate fertile farmland.

From that moment, Ye City became prosperous. Adequate food supplies laid the foundation for population growth and political importance. By the late Eastern Han Dynasty, chaos engulfed the land. Cao Cao defeated Yuan Shao and made Ye City his headquarters, drawn by its strategic location—controlling the north, guarding the Yellow River to the south, and offering flexible troop movements.

Cao Cao also developed the city with grand projects, including the Bronze Sparrow Terrace, a complex of three towering platforms connected by bridges, offering panoramic views of the surrounding plains. Beyond architecture, Ye City became a cultural hub. Cao Cao, his sons, and the Seven Scholars of Jian’an gathered at the terrace to compose poetry and drink wine. Renowned poet Cai Wenji even performed the melancholic Hu Jia. Jian’an literature emerged from this vibrant cultural atmosphere, later celebrated as the “Jian’an Style,” a defining chapter in Chinese literary history.

Ye City maintained its significance even after Cao Wei fell. Successive dynasties, including Later Zhao, Ran Wei, and Former Yan, established their capitals here. During the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi, the city reached its zenith. The newly built Ye South City spanned over twenty square kilometers, housing more than 500,000 people.

Unlike Luoyang or Chang’an, Ye City’s urban planning was advanced: the palace was in the north, government offices in the center, commercial districts in the south, and military and craft areas neatly divided along the sides, forming a grid-like layout.

The city’s religious atmosphere was remarkable. Historical records show over 4,000 temples with 80,000 monks and nuns, meaning roughly one in six residents was a monastic. The ringing of temple bells and chanting became the city’s background music. The Xiangtang Mountain Grottoes, created during this period, remain treasures of Buddhist art. Visitors today can still see exquisitely carved statues, each expressing distinct emotions and artistry, showcasing the wisdom of ancient craftsmen.

Fire and Devastation

Ye City’s turning point came after the fall of Northern Qi. In 577 CE, the Northern Zhou army captured the city. Though no longer a capital, it remained strategically important. Three years later, Yang Jian, preparing to usurp power, faced resistance from Wei Chi Jiong, the stationed commander and a revered military leader. Ye City once again became a battlefield. Wei Chi Jiong was eventually defeated and killed.

To eliminate future threats, Yang Jian ordered the city destroyed. For a month, flames consumed the Bronze Sparrow Terrace, over 4,000 temples, marketplaces, palaces, and residences, turning them to ashes. Residents were forcibly relocated to Xin Anyang, over forty miles away. Neglected canals silted over, and Ye City vanished beneath the earth. By the Song Dynasty, even the name “Ye” disappeared from official records.

Rediscovery from Ruins

Ye City slept underground for over 1,400 years until modern archaeology gradually unveiled its remnants. In the 1950s, excavations in Linzhang County uncovered city walls and artifacts, astonishing scholars with the city’s preserved structure beneath the soil.

Decades of research culminated in 2012 with the excavation of the Beiwuzhuang Buddha Pit, yielding nearly 3,000 statues. Archaeologists described the experience as surreal—“as the soil was cleared, the eyes of the Buddhas seemed to watch us.” The statues, with detailed craftsmanship and traces of original painting, were hailed as a miracle in Chinese Buddhist archaeology.

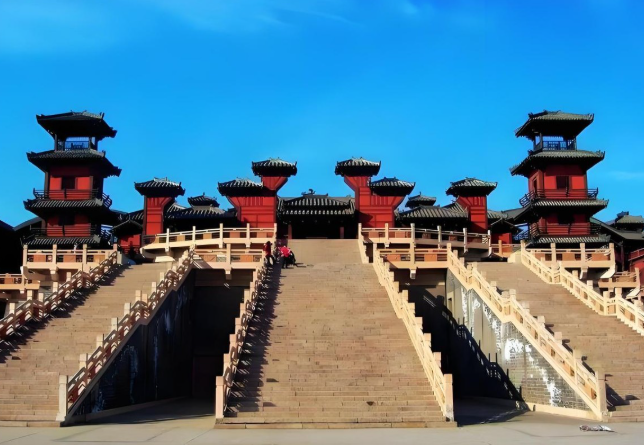

Today, visitors to Ye City’s ruins can glimpse echoes of its past grandeur. Though the Bronze Sparrow Terrace is mostly destroyed, the Jin Feng Terrace still stands twelve meters high, where the wind whispers and the echoes of Cao Zhi’s poetry seem to linger. The Zhu Ming Gate, with a width of forty-one meters, surpasses Beijing’s Meridian Gate in scale.

In 2019, the Ye City Museum opened, displaying giant stone dragon heads from palace drainage systems and carefully arranged Buddhist statues from Beiwuzhuang. Their expressions—compassionate or solemn—allow visitors to feel history’s presence.

Though Ye City was destroyed, its cultural essence endures. The resilient Jian’an literary spirit, the grand city layout, and the exquisite artistry live on, embedded in the bloodline of Chinese civilization.