In 202 BCE, after defeating Xiang Yu, Liu Bang proclaimed the Western Han Dynasty at Sishui in Shandong. The Records of the Grand Historian notes: “With the realm pacified, Emperor Gaozu made Luoyang the capital, and all vassals submitted.” Yet, he soon relocated the capital to present-day Xi’an, then called Chang’an, meaning “lasting peace.” The Eastern Han chose Luoyang, but the Sui and Tang dynasties returned to Xi’an. Centuries later, in 1260, Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty’s capital at Shangdu. After resolving a succession dispute with his brother Ariq Böke in 1264, he moved the capital to Yanjing (renamed Dadu in 1272, meaning “great capital” in Turkic), keeping Shangdu as a secondary capital. From then on, the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties all chose Beijing (named during the Ming to distinguish it from the southern capital, Nanjing).

Why did the Han and Tang dynasties favor Xi’an, while the Yuan, Ming, and Qing opted for Beijing? Ancient Chinese capital choices weren’t arbitrary; they were driven by deep, objective necessities. Let’s explore the reasons behind this historic shift.

Why Han and Tang Chose Xi’an

The Han and Tang dynasties’ preference for Xi’an (Chang’an) stemmed from shared and unique factors.

Shared Reasons

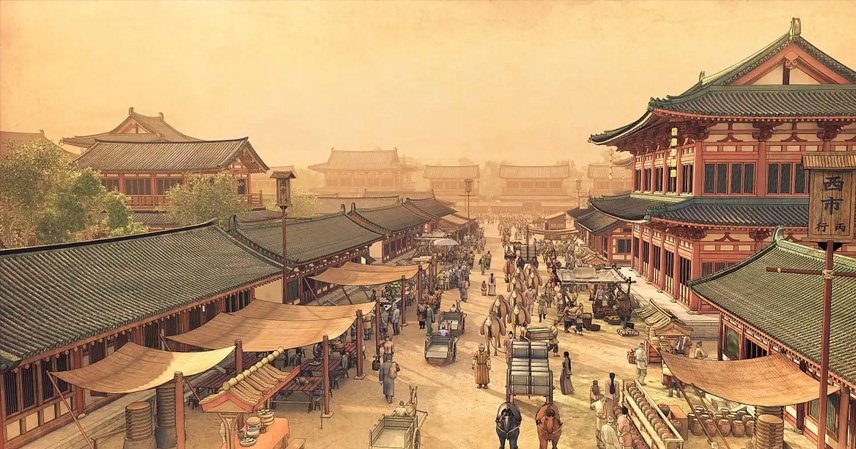

- Strategic Geography: Liu Bang initially favored Luoyang, but advisors Lou Jing and Zhang Liang argued it was vulnerable, “surrounded by enemies on all sides.” Xi’an, in the Guanzhong region, offered unmatched advantages: “encircled by mountains, girded by rivers, fortified on all sides.” The Guanzhong Plain—spanning roughly 36,000 square kilometers, larger than Egypt’s Nile Delta—was a “land of a thousand miles, a heavenly storehouse.” Compared to Luoyang’s smaller Yiluo Plain, Xi’an was ideal for long-term rule. Liu Bang, convinced, granted Lou Jing the imperial surname Liu and moved the capital to Chang’an. The Tang followed suit for similar reasons.

- Economic and Political Hub: During the Han and Tang, China’s political and economic center lay in Guanzhong, southern Shanxi, and central-western Henan. Choosing a capital within this core was logical. Liu Bang’s hometown, Xuzhou, was too peripheral to govern effectively. Xi’an, nestled in the fertile Guanzhong Plain, was perfect: defensible with surrounding mountains and self-sufficient with vast farmlands to feed the capital.

- Defense Against Northern Threats: The Han faced the Xiongnu, and the early Tang contended with the Turks, both nomadic threats from the northwest. Xi’an’s proximity to the frontier allowed for rapid military deployment and defense. Aligning the political and military centers strengthened its capital status. The Guanzhong’s terrain also shielded against invasions, making Xi’an a strategic stronghold.

Tang-Specific Reasons

Unlike Liu Bang, Li Yuan (Tang founder) was a Chang’an native, and his power base was the Guanlong Group—a coalition of military aristocrats from Shaanxi’s Guanzhong and Gansu’s Longshan (or Liupan) regions. This regional allegiance locked the capital in Xi’an. Later Tang emperors considered moving to Luoyang to curb the Guanlong Group’s influence, but Xi’an remained the anchor.

In short, Xi’an was the “chosen city” for Han and Tang, driven by geography, economics, and defense—not whim.

Why Yuan, Ming, and Qing Chose Beijing

If Xi’an was so ideal, why did later dynasties like the Song (Kaifeng) and Yuan, Ming, and Qing (Beijing) abandon it? Xi’an had two critical flaws:

- Food Supply Strain: The New Book of Tang notes: “Chang’an, though fertile, has limited land, insufficient to supply the capital or buffer droughts.” In Han times, Guanzhong’s resources sufficed, but as the population grew, food shortages loomed. The Grand Canal shipped grain to Luoyang, but the Sanmenxia Gorge made transport to Xi’an costly, leading to “expensive rice in Chang’an.” Sui and Tang emperors often worked from Luoyang to access food.

- Geographic Isolation: Xi’an’s “mountain-river fortress” was a strength but also a liability. By the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing, China’s economic center had shifted to the North China Plain and Yangtze Delta. A capital in Xi’an became too remote, isolating rulers from these thriving regions and hindering governance.

As times changed, Xi’an lost its edge. Why, then, Beijing for the Yuan, Ming, and Qing?

Yuan and Qing: Eastern Power Bases

The Mongol Yuan and Manchu Qing originated in the northeast, making Beijing a natural fit. Kublai Khan initially chose Shangdu, but its northern location hindered control over the Central Plains. Beijing offered balance: close to the grasslands for retreat or advance, yet commanding the vast plains southward, ideal for cavalry warfare. Controlling Beijing meant holding the Yanyun defense line, securing strategic dominance over the Yellow and Huai rivers.

Ming: Securing the North

For the Ming, holding the Yanyun defense line was critical to shield the north from nomadic incursions. Losing it would expose the heartland to attack—a lesson underscored by Ming general Yuan Chonghuan’s strategic missteps. When Zhu Di moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing, conditions were ripe: the economic shift northward and the need to secure the frontier made it essential. Claims that Zhu Di fled Nanjing’s hostile politics oversimplify the strategic necessity.

Economic Trade-Offs

Beijing wasn’t perfect. Its location demanded massive grain shipments via the Grand Canal, incurring high costs in manpower and resources. Yet, the strategic benefits—control over the plains and proximity to the frontier—outweighed these drawbacks for the Yuan, Ming, and Qing.

A Hypothetical Scenario

What if Hong Xiuquan’s Taiping Heavenly Kingdom had temporarily driven the Qing out of the heartland? Where would they have set their capital? The rational choice remains Beijing. It offered control over the northern plains, proximity to the frontier, and alignment with the era’s strategic realities—a testament to the enduring logic of capital placement.

The shift from Xi’an to Beijing reflects evolving times and the interplay between Central Plains and nomadic forces. No capital was chosen lightly; each was a calculated response to geography, economy, and defense.

References

- Records of the Grand Historian

- New Book of Tang: Treatise on Food and Goods