Space exploration has never been merely a technological contest; it is a comprehensive demonstration of national strength. China’s achievements in space, from the stable operation of its space station to steady progress in lunar missions, show a solid foundation for crewed lunar landings.

But why not act immediately and set the goal before 2030? The answer lies in strategic considerations, particularly in the space competition with the United States — a form of “open stratagem” that forces rivals into a reactive position.

During the 1960s, the U.S.–Soviet Cold War rivalry drove the Apollo program. While the U.S. achieved crewed lunar landings, it was largely a political symbol, constrained by technological limitations such as single-use rockets and high costs.

Today, the global space landscape has shifted. China, leading with indigenous innovation, has built a complete system from rockets to spacecraft. The Long March series has undergone multiple iterations, enhancing payload capacity. Long March 5 has successfully launched space station modules, while Long March 10 is entering critical development stages.

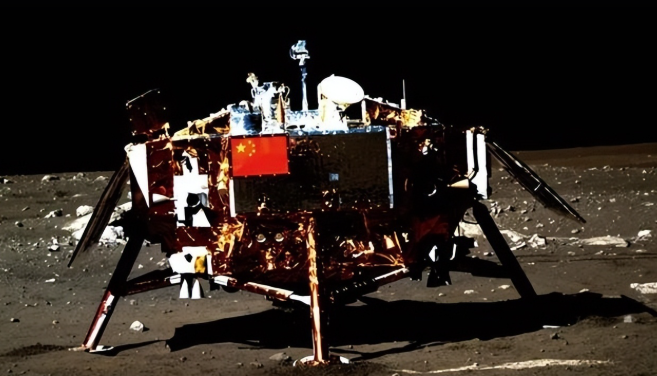

These advances are cumulative, achieved through the Chang’e lunar program: from orbiting the Moon with Chang’e 1 to sample returns with Chang’e 5, each mission validating key technologies.

China possesses the capability for crewed lunar missions. The space station has operated for years, astronauts have accumulated over a thousand days in orbit, and life-support and rendezvous technologies are well-practiced. This experience directly informs lunar operations. For instance, the Mengzhou spacecraft inherits the Shenzhou design but with an expanded cabin and improved oxygen circulation, enabling longer journeys.

Lunar landers are tested on Earth under simulated lunar conditions, with optimized landing sequences for stability. Compared to earlier lunar missions, precision has greatly improved: landing errors have decreased from kilometers to meters, and rover endurance has extended from days to months.

However, capability does not demand haste. Crewed lunar missions involve multiple risks and require coordination of funding and manpower. While Chang’e missions’ costs are controlled (~$1.8 billion total), crewed missions will be exponentially more expensive, requiring alignment with national development priorities.

China adopts a staged launch approach: first sending landers into orbit, then spacecraft for docking. This is more flexible and risk-dispersed than Apollo’s single giant rocket. Safety remains paramount; astronaut training encompasses radiation simulations and geological sampling, with repeated verification to avoid avoidable hazards.

The 2030 timeline reflects rational evaluation. Preliminary engineering is underway, with key challenges progressing smoothly. Long March 10’s engines have successfully completed integrated tests, achieving over 25 tons payload for Earth–Moon transfer.

Similar to space station missions but at distances hundreds of thousands of kilometers greater, signal delays are compensated via algorithms to ensure precise docking. Lunar suits (Wangyu) feature improved joint flexibility and wear resistance, supporting extended surface operations.

These upgrades are targeted for the lunar environment rather than simple replication.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Artemis program, originally ambitious for a 2025 landing, has faced repeated delays: Orion capsule heat shield damage, Starship rocket explosions, lagging landing systems, budget overruns, and contractor coordination issues. Although Starship holds potential, stability remains insufficient, and ground infrastructure repairs are time-consuming. These challenges expose weaknesses in the U.S. model, which relies heavily on private companies and under political pressure may prioritize schedule over technological maturity.

China’s 2030 plan cleverly leverages this contrast: by openly announcing a timeline, it avoids short-term race pressure while demonstrating capability. U.S. urgency to return to the Moon, despite frequent delays, self-undermines.

U.S. plans are also exclusionary, raising questions about sustainability among allies. China, in contrast, emphasizes science and cooperation, with an international lunar research station concept drawing global partners. By 2030, China aims to achieve crewed Earth–Moon transfers, surface stays, and independent capability — highlighting a second-mover advantage.

Open stratagem is central: transparent, steady progress. Chang’e 6 (2024) returned samples from the lunar far side, providing geological insights for landing site selection. Chang’e 7 (2026) will test polar exploration and resource utilization. These sequential steps minimize risk. Compared with Starship’s explosive test failures, China emphasizes data accumulation and maintains high success rates.

This strategy has proven effective: U.S. attempts to contain Chinese space tech have faltered; delays highlight China as a more reliable partner. Exchanges of lunar samples further demonstrate confidence.

2030 is not delay; it is accumulation. By then, China will not only land astronauts but establish research stations and develop lunar resources, advancing humanity’s space progress.

Space has no borders, but capability determines influence. China’s 2030 approach signals to the U.S.: “You rush, we consolidate; you expend, we accumulate.” Lunar footprints will reveal who has the more solid foundation.

This stratagem also reflects technological autonomy. Apollo-era rovers are now dormant; China’s Yutu has worked for eight years, and the planned “Explorer” rover will feature centimeter-level obstacle avoidance. Naming symbolizes scientific spirit, marking the shift from follower to competitor.

Unlike U.S. private-driven models, China coordinates nationally, minimizing private-sector risk. By 2030, a Chinese flag will fly on the Moon, with resources like helium-3 serving energy needs.

Finally, this open stratagem promotes peaceful space use. While U.S. politics may overlook collaboration, China builds inclusive frameworks. A basic international lunar station is expected by 2028 to validate environmental monitoring.

Currently, Shenzhou 21 is being prepared, with astronaut training focused on lunar operations. These advances solidify China’s strategic position.

This stratagem is more than spaceflight; it is a manifestation of national wisdom. China has the strength but chooses the optimal path, letting rivals reflect in anxiety. The Moon awaits China.