In a move that underscores the growing fusion of geopolitics and high technology, Dutch lithography giant ASML has reportedly promised the United States that, in the event of a military conflict in the Taiwan Strait, it will remotely disable TSMC’s extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines.

What sounds like a scene from a science fiction movie — technology weaponized by remote control — is, in reality, a reflection of how deeply intertwined global industry and political power have become.

Behind this “technical contingency plan” lies a far more complex story: a global supply chain built on trust and dependence, now being reshaped by fear and strategic control.

Technology as a Tool — and a Trap

ASML’s EUV lithography systems are the most advanced industrial machines ever built, essential for producing cutting-edge chips used by Apple, Qualcomm, and NVIDIA. TSMC operates over a hundred of them in Taiwan, powering much of the world’s semiconductor production.

Each EUV machine, priced at around $200 million, is equipped with a remote maintenance and diagnostic system — ostensibly for service support. But this same system could also act as a backdoor.

Industry insiders acknowledge that ASML could, in theory, lock or deactivate the machines remotely by disabling key functions or cutting software access. “It’s technically possible,” said one former semiconductor engineer. “No one wants to admit it publicly — but everyone knows.”

In short, the machines that sustain the digital world are not fully controlled by those who operate them.

Washington Holds the Switch, Not Amsterdam

While ASML is a Dutch company, its strategic allegiance lies elsewhere.

Nearly a quarter of its ownership is held by major U.S. investment funds, including Capital Group and BlackRock. More importantly, key components of the EUV system — such as light sources, optical modules, and control software — originate from American suppliers.

This structure gives Washington both technical leverage and legal authority to dictate how ASML’s technology is used.

In 2023, under U.S. pressure, the Dutch government imposed new restrictions on exporting advanced lithography equipment to China — despite domestic opposition. ASML’s CEO Peter Wennink complained that “the U.S. is overreaching,” yet compliance was not optional.

According to Bloomberg, Washington privately asked ASML and the Taiwanese authorities to cooperate on an emergency plan: if the People’s Liberation Army moves on Taiwan, TSMC’s EUV tools should be immediately deactivated to prevent “technological capture.”

Behind the rhetoric of “protection” lies a strategic reality: TSMC is not an ally, but a pawn.

TSMC: The Heart of Chips, the Hostage of Strategy

TSMC is the world’s most advanced chip manufacturer — but also its most vulnerable. The company powers global technology giants, yet sits at the epicenter of geopolitical tension.

To reduce exposure, TSMC has expanded production in the U.S., Japan, and Germany, but its most advanced processes — 3nm and beyond — remain concentrated in Taiwan. In a conflict scenario, that capacity could vanish overnight.

Washington’s “support” for TSMC’s overseas expansion is not purely altruistic. By relocating advanced production to Arizona, the U.S. is ensuring that the world’s chip brain moves onto American soil.

TSMC’s Arizona plant — heavily subsidized and politically celebrated — has also faced delays, skill shortages, and cost overruns, exposing the gap between American ambition and industrial execution.

In essence, TSMC’s global footprint may diversify its geography, but not its autonomy.

ASML’s Remote “Kill Switch”: A Dangerous Precedent

If ASML indeed possesses — and agrees to use — a remote shutdown mechanism, it would mark a historic turning point in industrial control.

For decades, the semiconductor supply chain was built on mutual trust: nations specialized, companies cooperated, and efficiency ruled. Now, technology has become a weapon of influence.

ASML’s “commitment” to Washington sets a precedent that could fracture global supply chains. Clients and governments worldwide are already asking: What if our critical equipment can be turned off, too?

The idea that a single company — or government — could paralyze another nation’s industrial lifeline raises a profound question: Where does technological dependence end, and digital sovereignty begin?

China’s Path: Building Its Own Key

China, long aware of this vulnerability, has accelerated efforts to localize semiconductor production.

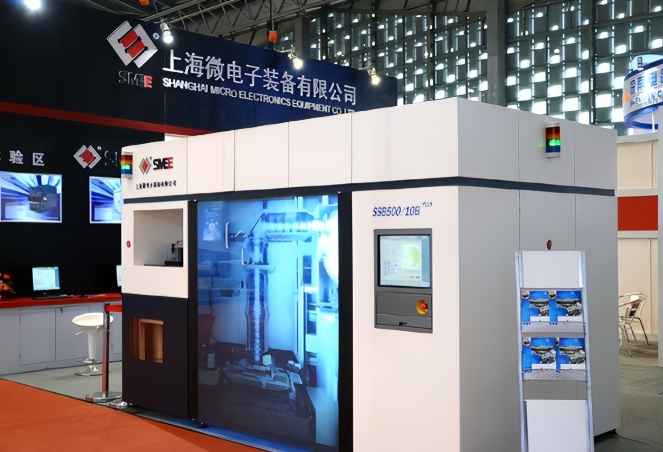

By 2024, domestic chipmaking equipment achieved 13% self-sufficiency, with strong progress in etching, cleaning, and coating systems. Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment (SMEE) delivered a 28nm lithography tool, while research institutions like Harbin Institute of Technology continue developing indigenous EUV light sources.

The third phase of China’s “Big Fund” injected over 340 billion yuan ($47 billion) in 2024, signaling a shift from fragmented projects to systemic technological independence.

While full replacement of ASML’s EUV technology remains years away, the direction is irreversible: China no longer waits for others to unlock the door — it’s forging its own key.

The Backfire of Tech Weaponization

ASML’s alignment with U.S. strategy may serve short-term geopolitical goals but risks long-term commercial damage.

Since 2023, its sales to mainland China have declined sharply, and every quarterly earnings report has triggered market volatility. Dutch lawmakers are questioning whether “sacrificing industrial neutrality” for U.S. security interests truly benefits the Netherlands.

Once clients lose confidence in the autonomy of their equipment, the global semiconductor ecosystem could fragment into regionalized, distrust-driven markets — the very opposite of the efficient, integrated model that enabled ASML’s rise.

Conclusion: Who Holds the Key to the Future?

ASML’s reported promise to “pull the plug” on TSMC symbolizes more than corporate compliance — it exposes the fragility of global technological interdependence.

Technology, once the engine of globalization, is now being weaponized as an instrument of control. Yet, as history shows, monopolies create the desire for alternatives.

For China, the lesson is clear: true security lies not in protest, but in self-reliance — in building not just chips, but the tools that make them.

For the world, the warning is equally stark: when one company or nation holds the switch, everyone else lives in uncertainty.

In the end, global safety will not come from shutting machines down — but from ensuring that every nation has the power to turn them on.

References

- Bloomberg, “U.S. Urged ASML to Cooperate with Taiwan in Contingency Planning,” 2024.

- NRC Handelsblad, “Dutch Firms Under Pressure in U.S.-China Tech War,” 2024.

- Xinhua News Agency, “China’s Semiconductor Equipment Industry Sees Rapid Growth,” 2024.

- Financial Times, “TSMC Arizona Factory Faces Delays and Cost Overruns,” 2024.