The morning breeze in the Jinzhong Basin carries the pine whispers from Lüliang Mountains and the misty vapors from the Fen River, gently brushing over the walls of Taiyuan. Stepping away from the hustle of the plains and into this Dragon City, you’re greeted not by the dry scent of loess soil, but by the profound weight of millennia of history. Encircled by mountains, Taiyuan unfolds like an ancient bronze tome, each page etched with the marks of time. Accustomed to the rush of modern cities, I found Taiyuan’s essence in its bones of mountains, veins of rivers, and soul of antiquity—a serene haven carved from the clamor.

Wandering Taiyuan’s streets, I realized the city’s beauty lies not in superficial glamour, but in the textures of its history: the morning dew on the eaves of Jinci Temple, condensing the piety of Zhou Dynasty lords; the patina of green rust on bronzes deep in the Shanxi Museum, whispering tales of Jin State’s dominance; even the steam rising from a fresh bowl of Xi Tang soup on the street, infused with the warmth of the land and the secrets of ages.

Impression 1: Jinci Temple – Millennia of Prayers Frozen in Wood and Stone

Nestled at the foot of Xuanweng Mountain amid ancient trees, stepping into Jinci Temple feels like entering a three-dimensional chronicle of Chinese architecture. As China’s oldest surviving royal sacrificial garden, every brick and tile is steeped in the patina of time. At its heart stands the Hall of the Holy Mother, its faded vermilion paint and weathered dougong brackets silently narrating the exquisite craftsmanship of North Song artisans. Before the hall, the Fish Marsh is spanned by a cruciform flying bridge like a soaring roc—a unique ancient bridge design that leaves posterity in awe.

The true soul awaits inside: 41 Song Dynasty colored clay statues of maidservants stand silently by the altar, their robes flowing, expressions varied. One seems about to smile while pinching a towel; another lowers her gaze in quiet sorrow. As if sealed by time, these glimpses of courtly life continue their wordless tale amid the curling incense. Emerging from the hall, the murmur of the Nanlao Spring weaves through the woods. This thousand-year-old clear spring contrasts with the 3,000-year-old Zhou cypress at the corner—one dynamic, one still—blending the vicissitudes of the Spring and Autumn Period with life’s resilience into every visitor’s breath.

Jinci’s magic is that it refuses to be a lifeless relic. An elderly man leans on a Ming Dynasty stone railing in contemplation; children chase birds flitting past the Golden Man Terrace’s iron statue. North Song wooden structures, Sui-Tang steles, and Yuan Dynasty pavilions blend with everyday city sounds and the fragrance of greenery, breathing life into the frozen architecture.

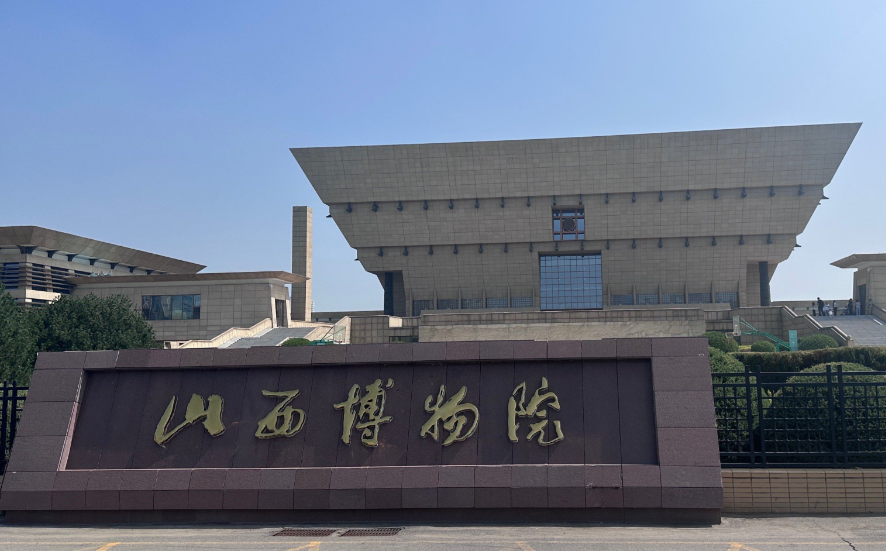

Impression 2: Shanxi Museum – Civilization’s Codes Unearthed from the Loess Layers

On the west bank of the Fen River, a tripod-shaped building rests quietly. Entering the Shanxi Museum is like stepping into a time tunnel paved with artifacts. With 500,000 collections—over 40,000 precious relics forming the “soul of Jin”—a beam of light in the dim hall illuminates the Bird Zun: a phoenix head turning back, elephant trunk curling, feathers etched in fine detail. This Jin State ritual vessel, shattered into hundreds of pieces and reborn through restoration, stands on the pedestal, its bronze sheen flickering with the reverence of Western Zhou nobility and ancient ingenuity.

The museum’s corridors fold time: from the Yangshao culture’s Taosi site pottery to the Jin State’s bronze chime bells; from Northern Wei Buddhist statues to Ming-Qing Jin merchant banknotes. Each piece is a historical code emerging from the yellow earth. Most touching are the traces of nameless craftsmen: the compassionate downcast eyes of Northern Dynasties Buddhas, the lively child-at-play motifs on Jin porcelain pillows, the still-vivid cinnabar in Ming water-land paintings after centuries.

Traversing the seven historical-cultural and five artistic exhibition halls feels like reading a three-dimensional scroll of Chinese civilization. As I left, glancing back, the tripod building glowed in the sunset like a massive bronze vessel—a dialogue between modern design and ancient legacy spanning three millennia.

Impression 3: Street Life’s Warmth – Taiyuan Memories on the Tip of the Tongue

As dusk tints the food street’s green tiles, Taiyuan’s flavors truly awaken. Amid rising steam at alley mouths, a pot of Xi Tang soup bubbles with milky waves. Select mutton simmers for eight hours, ancestral broth poured into rough porcelain bowls, garnished with fresh green coriander—its savory aroma piercing straight to the soul. In the summer of 2025, this humble shop’s Xi Tang soup officially joined China’s landmark cuisines, a warm calling card from Taiyuan to the world.

Around the corner, in an old-brand shop, intangible heritage dances at fingertips. Master Zhao Guangjin’s hands fly over the dough, pressing deep with palms, pushing forward with full body force. The Guodu Lin mooncakes come alive through a thousand kneads. The baking aroma fills the streets; fresh-from-oven cakes have crisp skins and soft fillings, needing a month in earthen jars to “ferment” to perfection. Born from a drunken mishap among the Guo, Du, and Lin masters three centuries ago, it’s now a totem of Taiyuan’s Mid-Autumn memories.

Taiyuan’s everyday flavors hide in such resilient traditions. Elders guard willow boards and jujube molds, kneading years into the dough’s chewiness; housewives tend bubbling Xi Tang pots, simmering life’s essence from time. In an era of machines replacing hands, these skills honed over decades transmit a warmth beyond food—a gentle force against transience.

Leaving Taiyuan, the rich aroma of Xi Tang lingers on my clothes, the texture of Jinci’s wooden pillars on my fingertips, and the mysterious outline of the Bird Zun in my mind. This Dragon City offers travelers not just towering twin pagodas or Jinci’s three wonders, but history’s living pulse in ordinary alleys: peonies blooming yearly at Yongzuo Temple in morning light, the kneading force of Guodu Lin mooncakes passed down generations, Jin River flowing from jade rings, nourishing Taiyuan’s lotus-walking people.

Taiyuan’s depth is the mottled patina on bronzes, the twisted branches of Tang cypresses, and the eight-hour-simmered fragrance of Xi Tang in kitchens. It unhurriedly tells every visitor: eternity is but the lingering echo of street life’s warmth through time.