A “Silent Strike” in the Semiconductor Race

In early October, China’s Ministry of Commerce issued a new regulation: any product containing more than 0.1% Chinese rare earths now requires export approval.

At first glance, it seems like a minor administrative adjustment. In reality, this move has sent shockwaves through the global semiconductor industry, particularly affecting TSMC, caught between the political and supply chain pressures of China and the U.S.

American tech giants relying on AI, meanwhile, are forced to reconsider the foundations of their “technological empire,” realizing that its supply chain is far less secure than previously assumed.

The Subtle Power of 0.1%

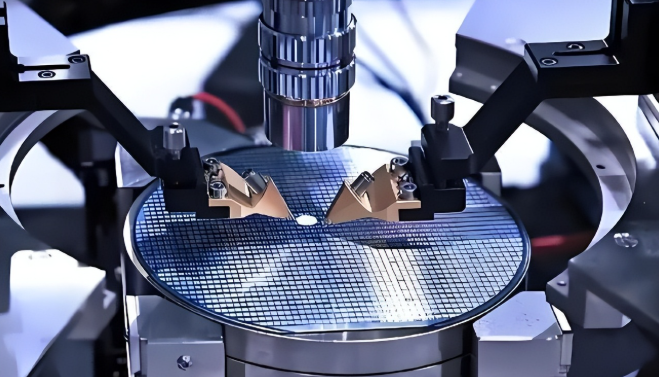

Although the 0.1% threshold appears trivial, it touches nearly every stage of high-end chip manufacturing—from photoresists and polishing liquids to laser equipment and magnetic components. The critical point: most of these rare earth materials originate in China.

China controls roughly 70% of global rare earth mining and over 90% of rare earth separation and magnet production.

To put it simply, China doesn’t just own the raw materials—it controls the entire production chain. The global semiconductor industry depends on this chain, whether for manufacturing, calibration, or component assembly.

TSMC: Caught Between Two Kitchens

Five years ago, TSMC was the centerpiece of the global chip ecosystem. Today, it’s stuck between two “kitchens”:

- 70% of its clients are American, including Nvidia, Qualcomm, and Apple.

- 96% of Taiwan’s rare earth supply relies on mainland China.

At its Nanjing plant, over 50 kg of neodymium-iron-boron magnets are consumed monthly for equipment calibration. In Kaohsiung, laser components are heavily dependent on Chinese materials. Even minor supply interruptions could halt production across entire facilities.

TSMC has explored alternative sources in Malaysia and Vietnam, and sought partnerships with Japanese and European firms. Yet outside China, few countries can consistently provide ultra-pure rare earths or manufacture high-integrity magnets—a technical and industrial bottleneck that “diversification” alone cannot solve.

Even TSMC’s Arizona facility struggles with progress delays, cost overruns, and talent shortages. Without China’s rare earth input, production of advanced chips is nearly impossible—a luxury kitchen without a flame to cook.

The Vulnerability Beneath America’s AI Tower

The rare earth regulation is a wake-up call for the U.S. AI and defense industries. For instance, Nvidia’s H100 AI chip, priced at $40,000, relies on ultra-pure dysprosium sourced exclusively from China.

This is not a replaceable material; high-performance standards require precise refining and processing. Even with U.S. design, factories, and talent, the ability to deliver depends on China’s “shipment approval.”

It’s more than business—it’s national security. The U.S. Department of Defense’s F-35 fighter, B-21 bomber, and advanced missile systems rely on rare earth magnets. RAND Corporation research indicates that a three-month halt in Chinese rare earth exports would suspend over 70% of U.S. defense contractors, grounding aircraft and slowing armament maintenance.

Even the CHIPS Act cannot solve this dependency. Rare earth extraction and purification are technically demanding; domestic efforts in Australia, Europe, and Japan are insufficient for global-scale supply.

Resource Sovereignty as Strategic Leverage

This rare earth maneuver underscores a broader reality: technology alone does not guarantee security or influence. China’s move demonstrates that control over critical resources is equally decisive.

China’s approach is legal, flexible, and precise: targeting high-end chips and AI applications, while leaving room for medical and research uses. It signals that China will no longer be passively feeding the global tech industry while others attempt to restrict its capabilities.

From being a supplier to becoming a rule-maker in the industry, China has achieved in a decade what others took decades to attempt.

The Bigger Picture

The TSMC supply dilemma is just a symptom of a larger geopolitical and technological game. Rare earths, though tiny in quantity, are central to chips, AI, and defense systems. Whoever controls them controls the leverage.

This is not merely an export restriction—it is a recalibration of global power and industrial rules. The future of technology is no longer just about who can design or manufacture chips; it is about who commands the resources that underpin the entire system.

References

- China Ministry of Commerce, Rare Earth Export Regulation, October 2025

- RAND Corporation, U.S. Defense Industry Supply Vulnerability, 2025

- TSMC Annual Reports and Production Data, 2025