China’s edible oil sector has undergone dramatic shifts over the past century and a half, evolving from a global export leader to a major importer navigating intense international competition. This narrative traces the industry’s highs and lows, highlighting how trade policies, foreign investments, and domestic strategies have reshaped soybean imports and local production. As of 2025, with Brazil dominating supplies and sustainability initiatives gaining traction, the story underscores the delicate balance between food security and global market forces.

Late Qing Export Surge

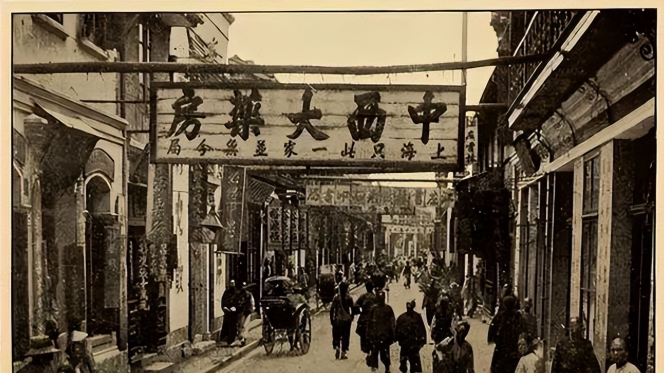

In the late Qing Dynasty, China’s edible oil exports, particularly tung oil and tea oil, commanded a significant share of the global market. Records from the Yuezhou Customs indicate that plant oils were the primary revenue generator for export duties, outpacing minerals and hardware. From the Republic’s seventh year (1918) to the fourteenth (1925), Hankou’s local goods export value rose from over 10 million taels to more than 15 million taels. Although imports grew faster overall, plant oils maintained steady dominance.

Western demand initially used these oils as kerosene lamp fuel before discovering their value in machine lubrication, spurring a surge in orders.

Tariff Walls and Market Collapse

However, this prosperity was short-lived. In the 1890s, U.S. factory owners lobbied Congress over high domestic oil prices, culminating in the 1922 Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act, which imposed up to 40% duties on Chinese plant oils. Britain, France, Germany, and Italy quickly followed suit, with customs in London, Marseille, and Hamburg effectively pricing Chinese products out of European markets. Rural oil mills shuttered, and exporters saw orders evaporate as these barriers severed access to key outlets.

Republican Era Headwinds

The Republican period brought further challenges. Post-World War I, international capital restructured supply chains, with Wall Street bankers funding European oil firms, eroding China’s market share. After regaining tariff autonomy, the Nanjing government’s Ministry of Finance introduced export tax exemptions and rebates to shield domestic industries, but discriminatory surtaxes persisted, hindering recovery.

Foreign entities deepened penetration, with American merchants acquiring peanut fields in Shandong to control production and processing. Pre-war, movements in North China boycotting foreign goods targeted these incursions, though limited in scale, they symbolized broader anti-imperialist sentiments.

Lard’s Traditional Hold and Emerging Threats

Amid this, lard—as the premier animal fat—retained cultural prominence, referenced in ancient texts like the Zhou rituals for its elite status in cooking. Essential in households for stir-frying and flavoring, it faced disruption from foreign-promoted hydrogenated plant oils, marketed as “modern and less greasy” through aggressive newspaper campaigns. Rising raw material costs squeezed local lard workshops, forcing adaptations.

Post-1949 Industrialization

Following the founding of the People’s Republic, state-led grain and oil processing plants proliferated, stabilizing lard supplies. Urban canteens brimmed with it, ensuring reliable access.

Reform Era: Foreign Re-entry

Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in 1978 reopened doors to foreign players. By the late 1980s, U.S.-based ADM executives pitched joint ventures in Beijing. In 1991, ADM entered the Chinese market, piloting soybean processing along the coast the next year.

By 1995, ADM acquired a feed premix plant in Dalian for animal nutrition and a soybean crushing facility at Shanhaiguan. Partnerships with China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Corporation (COFCO) led to eight joint ventures, capturing nearly a quarter of China’s edible oil supply. Founded in 1905 in Illinois, ADM— the world’s largest processor of corn, wheat, and oilseeds—derives two-thirds of its revenue from soybean oil, eyeing China’s vast population.

Golden Dragon Fish and Packaging Revolution

In 1996, Golden Dragon Fish (Wilmar International, a Singaporean firm entering China in 1991) launched its first CCTV ad with the “1:1:1 blended oil” slogan, sparking a shift from bulk to packaged oils. The campaign “Golden Light Shines on the Divine Land” resonated with housewives embracing modernization. Tying oil to health appealed to rising affluence, boosting market share from 39.5% in 2017 to 38.4% in 2019. Per capita oil consumption jumped from 3 kg in 1979 to 14 kg in 1999, with plant oils overtaking lard.

The ABCD Giants’ Dominance

The “ABCD” quartet—ADM, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus—longtime controllers of global grain chains, intensified their hold after China’s 2001 WTO accession opened the soybean market. Bunge built in Nanjing, Cargill expanded in Tianjin, and Louis Dreyfus stockpiled palm oil in Shanghai. While competing on surface, they influenced Chicago Board of Trade futures, pressuring local prices.

Lard suffered as ads vilified saturated fats; its supermarket share plummeted from 70% in 1990 to 20% by 2000. Northeastern slaughterhouses processed fewer fat trims, and home cooks switched to clearer plant oils, diluting traditional flavors.

2004 Soybean Shockwave

By 2003, China’s soybean imports exceeded domestic output, with high transport costs discouraging Northeast farmers. Genetically modified beans from Brazil (64.1%), the U.S. (25.8%), and Argentina dominated 97% of imports. The 2004 crisis saw international funds speculate prices from $200 to $400 per ton, bankrupting over 1,000 crushers—80% snapped up by ABCD firms. An estimated 1.3 million farmers abandoned crops, triggering job losses.

ADM alone controlled 13 firms, holding 85% of processing capacity. U.S. Department of Agriculture data was accused of inflating rallies before short-selling crashes, leaving Chinese buyers holding the bag. Coastal plants favored by foreigners left inland beans unprofitable, pushing farmers to corn and deepening import reliance.

COFCO’s Strategic Pushback

COFCO mounted a response, venturing into South America post-2004. In 2006, it invested in Argentina; by 2014, acquiring 50% of Nidera, and fully purchasing Noble Agri in 2015 for $750 million. Brazilian projects followed, with warehouses rising at Santos port.

Policies tightened import quotas, subsidized Northeast soybeans, and mechanized Heilongjiang fields. By 2016, ABCD’s Brazilian share waned as COFCO direct-sourced. In 2017, full control of Nidera expanded South American seedbeds; 2018 saw COFCO lead Brazilian soy exports through land acquisitions.

2025: A Turning Point in Trade Flows

As of 2025, COFCO’s $285 million mega-terminal at Santos—the largest export facility outside China—handles soybeans, corn, and sugar, projecting 8 million tons throughput, including 5.5 million of soy and corn. In May, a 69,000-ton sustainable soybean shipment from Brazil to China set a precedent for deforestation-free chains by year-end. July saw the first Responsible Agriculture Standard soy delivery to Thailand, forging green supply links.

China’s soybean imports hit 86.18 million tons in the first nine months, up 5.3% year-on-year, with Brazil claiming 79.9%—a record—while U.S. volumes dipped below 20% amid trade tensions. COFCO’s South American and Black Sea grain corridors, bolstered by port investments, signal loosening foreign grips. Northeastern fields are rebounding with green waves of soy.

Yet, the battle persists. Foreign agribusiness prioritizes profits, with pricing power in U.S. and Brazilian hands. From farm to table, domestic firms face squeezes, but initiatives like COFCO’s underscore a push for soybean import sovereignty and sustainable practices.

References

- Bin Wong, R. (Historical analysis on Qing tariffs).

- U.S. Congress: Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act (1922).

- COFCO International Newsroom (2025 shipments and terminal updates).

- USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (Soybean import data).

- Reuters: Brazil soybean exports (2025).