1. The Post-Holiday Surge of Policy Moves

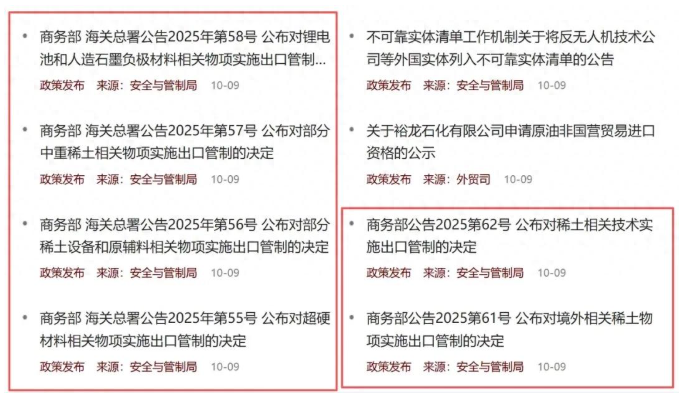

On October 8, while most of China’s workforce was still recovering from the weeklong National Day holiday, the Ministry of Commerce resumed work with unusual vigor. Within one day, it issued six separate announcements — two in the morning and four in the afternoon — all related to export controls on critical minerals and technologies. The timing and intensity of this move signaled that Beijing was not merely regulating an industry, but sending a geopolitical message.

For Washington, the gesture landed unexpectedly. Just as the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) had expanded semiconductor export restrictions days earlier, Beijing’s “rare earth counter” arrived as a precise and symbolic response.

2. Are Rare Earths Really Rare?

Geologically speaking, rare earth elements (REEs) are not truly rare; their name reflects the difficulty of extraction and purification, not scarcity in the earth’s crust. Yet over decades, China turned this technical challenge into an industrial advantage. Through a full-cycle ecosystem — from mining, refining, and separation to advanced magnet production and recycling — China built a near-monopoly across the global supply chain.

Attempts by the United States and its allies to replicate this ecosystem have repeatedly run into obstacles. The Mountain Pass mine in California, once hailed as the cornerstone of U.S. rare earth independence, has faced persistent issues: environmental restrictions, cost overruns, and dependence on Chinese processing technology. Even when ores are mined domestically, they often end up being refined in China.

3. The Trigger Behind Beijing’s Six Announcements

On September 27, the U.S. Department of Commerce introduced a new round of sanctions tightening its semiconductor export control regime. The updated “Entity List” applied collective penalties not only to listed firms but also to their subsidiaries and affiliates. The logic was clear: better to overreach than to leave loopholes.

China’s subsequent response — a series of regulatory updates on rare earth and battery material exports — can thus be read as a calibrated reaction. These measures were not random administrative acts but deliberate counterweights in a widening technological contest.

4. What the Six Announcements Really Mean

Behind the bureaucratic language, the new Chinese export controls contain several critical implications:

- Technology Licensing Tightened: Exporting rare earth processing technologies now requires specific licenses, effectively closing the door to unauthorized technology transfers.

- Expanded Scope to Battery Materials: The inclusion of lithium cathode precursors links the policy directly to the electric vehicle (EV) supply chain — a sector where U.S. firms like Tesla are heavily exposed.

- Crackdown on Re-exports: China explicitly targeted “transshipment” via offshore intermediaries, a mechanism often used by Western trading companies to bypass direct trade channels.

- Legal Accountability: Violations of these controls may lead to criminal prosecution, adding a layer of deterrence that elevates the measure from an economic policy to a strategic instrument.

5. The U.S. Struggle to Rebuild a Supply Chain

Washington’s ambition to establish a self-sufficient rare earth industry faces multiple structural barriers:

- Environmental Constraints: Rare earth processing generates radioactive waste, which conflicts with U.S. environmental regulations and public opinion.

- Talent Shortage: Decades of outsourcing have hollowed out America’s expertise in this field. Few universities maintain active programs in rare earth metallurgy or materials science.

- Cost Gap: The cost of refining rare earths in the U.S. remains several times higher than in China, making commercial viability elusive without sustained subsidies.

- Time Horizon: While China’s industrial system evolved over four decades, U.S. policymakers expect results within a few election cycles — a mismatch between industrial reality and political impatience.

6. Chip Sanctions and Rare Earth Controls: A Strategic Symbiosis

The confrontation between U.S. semiconductor sanctions and Chinese rare earth restrictions illustrates a new phase of interdependence-driven rivalry. Both sides hold crucial positions in different layers of the global tech ecosystem — the U.S. dominates chip design and equipment, while China commands materials and processing capabilities.

The asymmetry is striking: semiconductors represent an annual global market exceeding $600 billion, while rare earths amount to roughly $80 billion. Yet, the latter’s strategic importance far outweighs its market value. Without rare earth magnets, advanced fighter jets, precision missiles, and electric vehicles would lose key functional components.

Pentagon analyses reportedly show that U.S. defense stockpiles could only sustain operations for a limited period in a full-scale conflict if rare earth imports were cut off. In that sense, Beijing’s leverage is not in volume but in indispensability.

7. The Decline of Trump’s “Art of the Deal”

Former President Donald Trump’s negotiating philosophy — to apply maximum pressure before offering selective concessions — worked with trade partners such as Mexico and Canada. But when applied to strategic materials like rare earths, it encounters a structural limit: the U.S. cannot negotiate leverage it does not possess.

China’s rare earth export controls effectively turned Washington’s pressure campaign into a two-front struggle — defending its semiconductor advantage while scrambling for material security. Following Beijing’s announcement, shares of U.S.-listed rare earth firms such as MP Materials fell sharply, reflecting investor anxiety about long-term supply stability.

8. From “Chip War” to “Resource War”

The global technology rivalry has evolved from a battle over semiconductor access to a broader contest over industrial resilience. In the short term, the two economies will likely continue a tit-for-tat pattern — chips versus minerals, sanctions versus countermeasures.

In the medium term, the U.S. may attempt to diversify supply through partnerships with Australia, Canada, and African producers. Yet the technical processing infrastructure remains largely in China’s hands.

In the long term, both sides may find themselves compelled to return to the negotiating table. Mutual technological suffocation benefits no one; interdependence, once weaponized, eventually becomes a shared vulnerability.

9. Conclusion: The Politics of “Non-Rarity”

Rare earths are not rare, but the capacity to refine and regulate them is. China’s latest export control package is not a declaration of economic nationalism, but a reminder of industrial realism — that in a globalized economy, strategic autonomy requires more than rhetoric.

For Washington, the lesson is equally clear: decoupling may offer political satisfaction but delivers economic friction. For Beijing, the challenge is to wield resource leverage without undermining its image as a reliable global supplier.

In the end, the “rare earth war” underscores a simple truth — in the 21st century, power is defined less by what a nation possesses, and more by what others cannot do without.

References:

- U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security announcements, September 2025.

- Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, Export Control Updates, October 2025.

- MP Materials Corp. investor statements and public filings.

- OECD Rare Earth Market Outlook Report (2024).