When the term “choke point technologies” became a buzzword in discussions about China’s manufacturing limitations, few noticed that the Chang’e lunar program was quietly rewriting that narrative through a series of groundbreaking achievements.

From the first full lunar map transmitted by Chang’e-1, to Chang’e-5’s successful return with lunar soil samples, and the Chang’e-6 mission that collected samples from the moon’s far side, China’s lunar exploration completed in two decades what took other powers half a century.

What makes this journey even more remarkable is its unwavering commitment to independent innovation. Every stage of the mission prioritized autonomous, controllable core technologies, breaking Western monopolies in aerospace and forcing the world to recognize China as not just a participant, but an emerging rule-maker in space exploration.

From Isolation to Independence

The space race has always been the ultimate stage for great-power competition. In the 20th century, the United States’ Apollo Program and the Soviet Luna Program cemented Western dominance in deep-space exploration.

From rocket engine design to lunar landing systems and deep-space communication networks, the West built near-impenetrable technological walls.

When China began its own lunar program, it faced not only skepticism but also strict technological embargoes — most notably the U.S. “Wolf Amendment”, which banned space cooperation with China. The intent was clear: to keep China outside the global space exploration “circle.”

Yet, isolation became a catalyst for self-reliance. Every advance of the Chang’e missions carries the mark of “Made in China.”

Engineering Breakthroughs: Building the Ladder to the Moon

One of the earliest and toughest challenges came from rocket propulsion. The hydrogen-oxygen engines used in the Long March 3A series were plagued by fuel leakage under extreme pressure and heat.

After thousands of tests, Chinese scientists developed a high-pressure staged combustion cycle, solving the leakage issue and improving thrust-to-weight ratios to world-class levels — a critical step that made China’s lunar “ladder” entirely self-sufficient.

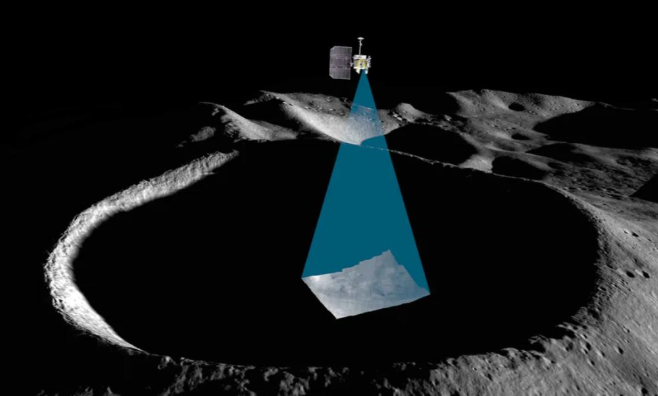

The soft-landing technology used by Chang’e-3 was another milestone — often described as “dancing on the tip of a knife.” Its Guidance, Navigation, and Control (GNC) system, fully developed domestically, enabled precise terrain recognition, hazard avoidance, and dynamic control during descent.

This precision even outperformed Russia’s Luna-25 lander, which failed its landing attempt in 2023.

Redefining Unmanned Lunar Exploration

Perhaps the most striking achievement came with Chang’e-5, which completed the world’s first unmanned lunar sample return mission.

The probe overcame numerous challenges — lunar drilling, sample sealing, and orbit transfer control between the Moon and Earth. Its robotic arm, equipped with dozens of advanced sensors, performed millimeter-level operations under vacuum and high-radiation conditions.

Before this, only the U.S. had achieved sample return — but through manned missions. China became the second nation ever, and the only one to do so robotically.

Meanwhile, Chang’e-4 made human history’s first soft landing on the Moon’s far side. Its relay satellite, Queqiao, established an Earth–Moon communication bridge, enabling continuous signal relay. Western agencies have since sought cooperation, recognizing the system’s technical superiority.

Turning Space Technology into Real-World Value

Beyond scientific prestige, the Chang’e program has demonstrated extraordinary commercial and industrial impact.

Its radioisotope thermoelectric generators now power deep-space missions, while autonomous navigation systems from lunar rovers have been repurposed for self-driving cars and smart agriculture.

Even thermal-control materials designed for spacecraft are now used in electric vehicle manufacturing.

This seamless technology transfer from aerospace to civilian sectors highlights the efficiency of China’s innovation ecosystem — a system capable of transforming “space breakthroughs” into tangible economic value.

From Blockade to Leadership

Ironically, the same Western countries that once blocked cooperation are now acknowledging China’s leadership.

The Director General of the European Space Agency (ESA) publicly stated that China’s capabilities in far-side lunar exploration and sample analysis are “world-leading,” expressing interest in closer collaboration.

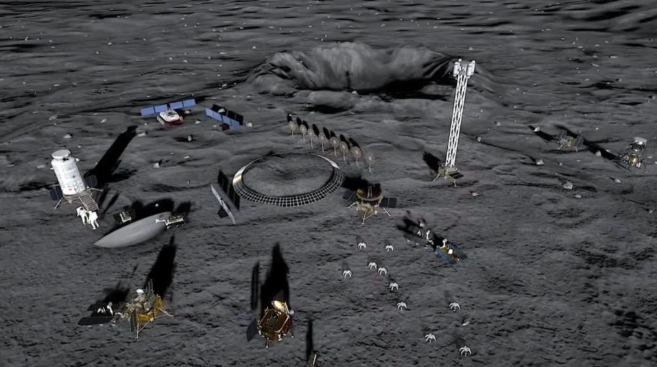

Yet, rather than replicating the technological monopoly model, China has launched the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) initiative — inviting global partners to jointly explore and utilize the Moon.

This model of “open autonomy” reflects a new form of national confidence: when core technologies are secure, cooperation becomes truly equal and voluntary.

Conclusion

From the mythical story of Chang’e flying to the Moon to today’s reality of robotic exploration, the program represents more than a technological feat — it’s a symbol of perseverance, innovation, and cultural continuity.

It also sends a broader message: so-called “choke points” are not unbreakable barriers. What matters is the determination to innovate independently, even under external pressure.

As China’s lunar missions continue to reach deeper into space, they embody a new development model for the world — autonomy as the foundation, openness as the path forward.

In the vast sea of stars, those who master both will go the farthest.

References:

- China National Space Administration (CNSA) Official Reports

- ESA Public Statements (2024–2025)

- Journal of Deep Space Exploration, Vol. 12, 2025