At 5:23 a.m. on June 4, 1928, a thunderous explosion near Huanggutun altered the course of modern Chinese history. The special train carrying Zhang Zuolin, the “King of the Northeast” who had ruled the region for 14 years, was destroyed by pre-planted explosives from the Kwantung Army. He perished on the spot. Historians widely agree that this event paved the way for the Mukden Incident three years later. But what if Zhang Zuolin had miraculously survived the assassination? Would the Japanese Kwantung Army still have the audacity to launch a full-scale invasion of China? Let’s dive deep into this counterfactual today.

Zhang Zuolin’s Strategy Toward Japan

Zhang Zuolin’s relationship with Japan always danced a tightrope between cooperation and confrontation. This grassroots warlord understood the rules of survival in the Russo-Japanese vise: he leveraged Japanese military and economic aid to solidify his rule while steadfastly guarding Northeast China’s sovereignty. After the 1927 Eastern Conference, Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Giichi proposed a series of “secret agreements” to Zhang, including extending the Jigda Railway, recognizing Japanese land and judicial rights in Manchuria—requests Zhang politely rebuffed. Instead, he built the Datong Railway and Huludao Port, actively courting British and American capital to counterbalance Japanese influence. This “align with the West, resist Japan” approach deeply irked Japan’s military establishment.

Zhang’s stance toward Japan was marked by pragmatic realism. During the 1925 Guo Songling rebellion against him, he reluctantly accepted some Japanese demands for military support, but once the crisis passed, he stalled on fulfillment with various excuses. In August 1927, Japanese Consul General in Fengtian Yoshio Yoshida’s negotiations on the “South Manchuria Railway parallel line issue” were shelved after sparking anti-Japanese protests from 100,000 Fengtian residents. This tactic of using public opinion to fend off Japanese pressure became a key tool in Zhang’s resistance to aggression. Kwantung Army Chief of Staff Kawamoto Daisaku later admitted in planning the assassination: “Zhang Zuolin is no longer controllable; he must be eliminated to resolve the Manchuria problem,” indirectly affirming how effectively Zhang had checked Japan’s expansionist ambitions.

In stark contrast to his son Zhang Xueliang’s later “non-resistance policy,” Zhang Zuolin grasped that weak nations have no diplomacy without dignity. Facing Japan’s relentless encroachments, he employed a “soft stall, hard stand” strategy: modest concessions on reasonable demands, unyielding defense of core sovereignty interests. This flexible yet resolute posture ensured Japan couldn’t achieve substantive gains through diplomacy before the Huanggutun incident. Zhang’s very existence was the greatest obstacle to Japan’s “Manchuria separation policy.”

The Military Strength of the Fengtian Army

Zhang Zuolin left behind not just political legacy in the Northeast but a military-industrial complex and armed forces rivaling Asia’s finest. By 1928, the Fengtian Army had swelled to a formidable force of 300,000 troops, with 100,000 elite soldiers equipped with advanced heavy weapons and robust logistics. On the eve of the Huanggutun incident, Heilongjiang warlord Wu Junsheng had rushed 50,000 troops to Fengtian for defense, while another 30,000–40,000 Fengtian forces hurried back from inside Shanhai Pass, forming a layered defensive perimeter.

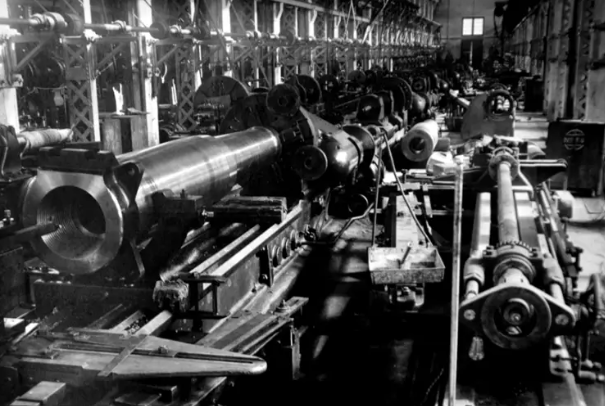

The Shenyang Arsenal’s output could sustain major war efforts—this powerhouse, Zhang’s brainchild, mass-produced rifles, machine guns, mortars, and even large-caliber artillery, boasting scale and tech unmatched in Asia. The Fengtian Army also commanded China’s strongest air force, with four squadrons and nearly 300 aircraft, including advanced fighters imported from France and Italy. On the naval front, the Northeast Navy controlled Bohai Bay with flagships like the Haqi. This integrated land-sea-air capability made the Fengtian forces China’s sole modern warfare contender at the time.

Crucially, Zhang built a self-sufficient defense industry. Beyond the Shenyang Arsenal, the region had mortar factories, ammo plants, and aircraft repair shops, enabling independent production of most munitions. This autonomy gave the Fengtian Army endurance in prolonged conflicts—unlike the Northeast Army’s 1931 withdrawal during the Mukden Incident due to ammo shortages. The Japanese Kwantung Army struck in 1931 precisely because it bet on a headless, disorganized foe; under Zhang, those vulnerabilities simply didn’t exist.

Iron-Fisted Control

Zhang Zuolin’s grip on the Fengtian Army rested on a web of loyalties that Zhang Xueliang could never match. Through sworn brotherhoods, hometown ties, and iron discipline, he forged absolute authority. Core commanders like Zhang Zuoxiang, Wu Junsheng, and Yang Yuting were either early blood brothers or handpicked loyalists. This personal loyalty-based chain of command, despite factional risks, generated fierce cohesion in foreign wars.

The swift post-Huanggutun stabilization and power transition proved the resilience of Zhang’s regime. Zhang Xueliang’s covert return to Shenyang and smooth succession, backed by elders like Zhang Zuoxiang, highlighted the system’s flexibility. Yet that flexibility hinged on a central figure—Zhang himself stabilized it, curbing elders’ ambitions like Yang Yuting’s while reining in young Turks like Guo Songling. This balancing act ensured unified command.

Compared to Chiang Kai-shek’s National Revolutionary Army, the Fengtian forces boasted stronger regional identity and autonomy. The Northeast, Zhang’s “dragon-rising land,” fused military and local interests into a tight-knit bloc. His “defend borders, secure the people” policy won broad backing from gentry and masses, crafting a civilian-military defense web that gave the army unique home-field edges.

Divergences Between Japan’s High Command and the Kwantung Army

Many mistakenly view the Mukden Incident as “Japan’s long-brewed master plan,” but from 1928–1931, Japan’s central high command (strategic decision-makers) and Kwantung Army (Northeast garrison) clashed sharply:

Kwantung Army: Radical Adventurists – Figures like Itagaki Seishiro and Doihara Kenji believed “without Zhang Zuolin’s death, the Northeast remains uncontrollable,” pushing for “military solutions.” Their confidence stemmed from expecting post-assassination disarray, not their own might—in 1931, the Kwantung Army numbered just 14,000, swelling to under 30,000 with reservists, backed by only 24 howitzers.

Imperial General Headquarters: Cautious Watchers – The high command fretted that “a full Northeast assault could defeat the Kwantung Army” and dreaded “international intervention” (with Western powers holding economic stakes, a rash war risked Anglo-American pressure). In 1929, it issued repeated “directives” to the Kwantung Army: “No unauthorized military actions without central approval.” Before the 1931 Mukden Incident, it even dispatched Operations Division Chief Tate Kawa Yoshitsugu to rein in the Kwantung Army (though futile, it showed their stance).

Had Zhang survived, these rifts would sharpen: The Kwantung Army would need high command buy-in by proving victory over the Fengtian Army—impossible against Zhang’s 350,000 troops, intact industry, and command. The Kwantung Army lacked even the muscle to seize Fengtian alone (1928 saw five Fengtian divisions—over 80,000 men—around the city), let alone a full invasion.

Thus, the Huanggutun incident wasn’t just Zhang’s tragedy but the Northeast defenses’ unraveling. Had he lived, Japan’s China ambitions would crash against this “iron wall.”

References

- The Cambridge History of China, Volume 12: Republican China 1912–1949, Part 1

- Zhang Zuolin: The Last King of Manchuria by Jonathan D. Spence

- Japan’s Imperial Army by Edward Drea

- The Search for Modern China by Jonathan D. Spence