The An Lushan Rebellion raged for eight years, with An Lushan initially routing the Tang forces step by step. So why did he ultimately lose? Because the Tang had a secret weapon—Li Bi.

This man was utterly unconventional: with strategies that could stabilize the dynasty, he stubbornly refused official posts, preferring to advise as a mere mountain recluse. Even more astonishing, after quelling the revolt, he shunned gold, silver, and titles, making just one odd request: to pillow his head on the emperor’s knee for a nap. Who exactly was Li Bi? Why dodge high office for these eccentric moves?

As a child, Li Bi was a true prodigy, composing essays at age seven that made him a local legend. In 728 AD, Emperor Xuanzong heard of this talented boy and had him brought to Chang’an.

That day, Xuanzong was playing chess with Chancellor Zhang. Spotting Li Bi, he decided to test him. Zhang, eyes on the board, challenged Li Bi to compose a fu poem on the theme of chessboard, pieces, and moves. Li Bi recited it on the spot—perfectly thematic and brimming with wisdom beyond his years. Xuanzong hailed him a prodigy and instructed his family to nurture him, enrolling them in the “Eastern Palace attendants” for support to aid his studies.

Word of Li Bi spread quickly among officials. Chancellor Zhang Jiuling invited him over, along with Yan Tingzhi and Xiao Cheng.

Yan, ever upright, disliked Xiao’s sycophancy and warned Zhang against getting too close. Zhang brushed it off and sent for Xiao. Li Bi then offered tactful counsel, snapping Zhang awake. He apologized profusely, warmly calling the boy “little friend.” Other notables like Zhang Tinggui and Wei Xuxin admired him too, but Li Bi showed little interest in courtly ties, fixated instead on scholarship and cultivation.

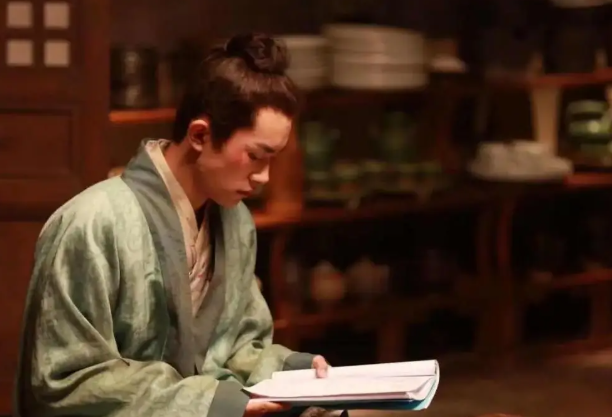

Grown-up Li Bi’s erudition deepened, yet he spurned officialdom. While others crammed for exams to enter service, he pored over the I Ching and delved into Daoist arts, seeking immortality. He often retreated to Mount Song, Mount Hua, or Zhongnan, visiting hermits and experimenting with alchemy.

He heeded imperial summons, though. Later, Xuanzong called him back to lecture Crown Prince Li Heng on the Laozi. Li Bi’s mastery shone through in clear, structured lessons that the prince adored, forging a deep bond.

But palace life soured him on Yang Guozhong’s tyranny and An Lushan’s scheming. Li Bi penned a poem subtly mocking their ambitions. Enraged, Yang exiled him to Qichun County on charges of slandering the court through verse. Unfazed, Li Bi quit the capital for the hills to pursue his spiritual path—if peace had held, he might have stayed a hermit alchemist forever. But the An Lushan Rebellion upended everything.

In 755 AD, An Lushan rebelled, Tang troops crumbled, and Xuanzong fled Chang’an in panic. Prince Li Heng ascended as Emperor Suzong in Lingwu. Fresh on the throne, Suzong recalled his old tutor and scoured the land, finding him in nearby mountains. Suzong offered the chancellorship to crush the revolt, but Li Bi flatly refused, insisting on mountain-man status as a mere imperial guest. Reluctantly, Suzong agreed, letting him advise on military affairs informally.

Though title-less, Li Bi became Suzong’s most trusted confidant. His pivotal strategy for victory: sidestep the rebels’ early momentum by sending Guo Ziyi and Li Guangbi to split forces into Hebei, severing supply lines and scattering foes before reclaiming territories piecemeal.

Generals like Guo and Li followed this playbook. After rebels took Chang’an, Li Bi urged Suzong against hasty recapture—instead, strike rear logistics, then pinch Luoyang to avoid clashing main forces head-on. It worked brilliantly, flipping the war and paving the way to retake the capitals.

Li Bi’s favor irked Chancellor Cui Yuan and eunuch Li Fuguo, who feared his influence and badmouthed him to Suzong. The emperor ignored them, even relaying the gossip to Li Bi. Unvindictive, Li Bi pondered retreat—he knew court intrigue’s venom too well.

In 757 AD, Tang forces retook Luoyang. Suzong promised grand rewards: high office, fiefs. Li Bi wanted none, claiming no taste for grains or family ties—past counsel was pure patriotism. With the capital freed, he asked only to nap on His Majesty’s knee, then have the court astronomers report a guest star invading the imperial throne in omen. That sufficed.

This echoed hermit Yan Guang’s subtlety, signaling his exit from power plays. Suzong, loath to lose him, yielded; Li Bi retired to Mount Heng, where the emperor decreed a “Recluse’s Chamber” for his meditations.

Later, under Emperors Daizong and Dezong, crises drew him back. Daizong summoned him against Tibetan incursions on Chang’an; Dezong, for warlord revolts and invasions, where he rose to chancellor, steadying the realm and mending rifts. But post-crisis, he’d resign each time, ever wary of bureaucratic snares.

Li Bi lived with rare clarity. Blessed with world-shaping talents, he shunned fame and fortune; in chaos, he steered salvation yet clung to liberty. His Daoist pursuits weren’t blind immortality quests but shields from strife; aiding Tang’s recovery stemmed not from power lust but national duty.

References

- Zizhi Tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government)

- Old Tang Book (Jiu Tangshu)

- New Tang Book (Xin Tangshu)