The sudden emergence of the Sanxingdui civilization wasn’t just a shock to everyday people—it left the archaeological community stunned when those massive bronze masks first appeared. This ancient culture popped up out of nowhere, bearing little resemblance to the Central Plains or the Western Regions, yet firmly rooted in the Sichuan Basin, in a spot that’s awkwardly perfect.

Many call it mysterious, but there’s a group of people who have long understood the “language” it speaks. Cone-shaped buns, protruding-eyed deities, inscribed symbols, vermilion copper artifacts… draw a line from them, and it leads straight to the Daliang Mountains, weaving into the Yi people’s epics, rituals, and beliefs.

To truly grasp Sanxingdui, you need to read Yi script, recognize the copper gods, and understand what “the eternal fire of copper smelting at Mount Tanglang” means. These aren’t myths—they’re evidence, echoes of a living culture.

The Bronze Masks Don’t Speak? Yi Script Might Understand

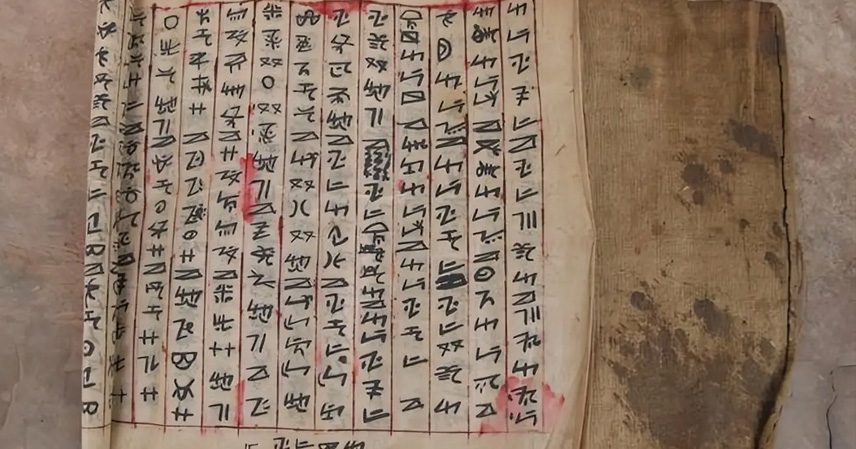

Sanxingdui had its own language and writing system. Symbols etched on unearthed bronze figurines, beast-face seals, and jade scepter shields are, in fact, writing.

The Sichuan Museum holds a bronze spear with continuous inscriptions along the blade’s central axis: three horizontal strokes, two verticals, and a hook—compact in structure, with deliberate starts and finishes, showing clear intent to form characters.

Researchers have proposed interpretations of these inscriptions since the 1990s, but progress was slow. It wasn’t until Yi script experts got involved that breakthroughs came.

Yi script belongs to the pictographic square-block character system, originating from a southern ethnic recording tradition about 3,000 years old. Modern Yi script preserves its core structure and still follows a subject-predicate-object order, strikingly consistent with the Sanxingdui inscriptions.

In 1995, Yunnan cultural historians successfully deciphered a set of inscriptions on a Sanxingdui bronze seal using ancient Yi characters. The content covered divine offices, directions, and clan names. The script blended horizontals and verticals, with complete sentence structures matching the ancient Yi writing system.

It’s not just grammatical alignment—character forms overlap too. For instance, the Yi word for “sun” is a central circle with radiating spokes, identical to the marks on Sanxingdui’s bronze sacred trees. The Yi character for “sacrifice” depicts a “person standing on a copper platform,” and Sanxingdui’s standing figures are precisely positioned on elevated platforms, hands clutching ritual objects.

The Yi classic Leper’s Scripture (Cham) records: “When humans first had divine speech but no words, they sacrificed to fire for script, and carved with knives for characters.” This mirrors the “fire-forged copper inscriptions” on Sanxingdui bronzes. The site’s artifacts heavily feature point engraving, scraping, and positive mold stamping, aligning with the “fire script” tradition described in Cham.

Sanxingdui’s “writing” isn’t incomprehensible—it’s about using the right tool, and Yi script is the key. If the site’s divine statues are speaking, they’re likely not in oracle bone script, but in a language the Yi people have remembered for a thousand years.

That Tuft of Hair on the Forehead? It Might Be the Real Key

Sanxingdui deities pay meticulous attention to their heads. Whether it’s the towering bronze standing figures or the gold-masked copper statues, one detail stands out: the cone-shaped bun.

This “cone bun” hairstyle is clearly documented in historical records. The Annals of the Kings of Shu describes Shu kings like Worm Bush, Cypress Irrigation, and Fish Fry as wearing “cone buns and left lapels, ignorant of writing.” That same cone bun lives on today in the Daliang Mountains.

Yi men tie their hair into a knot upon adulthood, called “zumo”; elders add ornaments, known as “ongbi”; and for weddings, it’s “zutie.” These three cone bun styles match the “high-bound knot, wrapped to the right” details on Sanxingdui standing figure heads.

The site’s premier bronze standing figure, 2.62 meters tall, sports an upright cone bun offset to the right center, with gold threads wrapping the roots—not mere decoration, but a ritualized emblem. In Yi culture, an adult man’s cone bun symbolizes status, age, and identity.

Historians note that Sanxingdui’s ancient Shu culture represents a branch of the Yi ancestors, who migrated south to Yunnan and Guizhou after defeat. The Yi epic Me Ge records: “The Yi originated from the Heavenly Bodhisattva, binding hair into crowns, crossing broken rivers.” The “Heavenly Bodhisattva” is a heroic archetype, an incarnation of the divine.

In Sanxingdui bronzes, the cone bun coexists with masks: heavy-set faces, elongated earlobes, and “protruding eyes” that perfectly align with The Chronicles of Huayang‘s description of “Worm Bush’s bulging eyes.”

Modern Yi elders still don cone buns in sky-worship ceremonies. During the Torch Festival in Zhaotong, Yunnan, clan leaders with high-bound hair wield bronze knives and wear vermilion copper bells on their chests, reenacting ancestral forms. Sanxingdui’s sacrificial pits yielded masses of bronze bells and divine figures holding ritual implements.

The bronze statues don’t move, but the hair doesn’t lie; a hairstyle passed down this long forms the skeleton of an ethnic group, a cultural testament “starting from the top.” No wonder people connect the two.

Where Did the Bronze Come From? Mount Tanglang’s Footprints Lead to Sanxingdui

Beyond script and hairstyles, plenty more links tie Sanxingdui to the Yi—like raw materials and casting techniques, woven with deep connections.

Sanxingdui’s copper didn’t come from the Western Regions or the Yellow River valley. Its ore veins, alloys, and smelting methods all point east to northeastern Yunnan.

Analysis of Sanxingdui bronzes shows copper as the base, tin secondary, with lead under 10%—a composition rare in the Central Plains but abundant in the Tanglang Mountains of northeastern Yunnan.

The Le Ruotiyi records: “Fire rises from Tanglang Mountain, copper flows from the earth, and Zhige Alu hammers the veins.” This isn’t legend—it’s ethnic memory of copper metallurgy’s origins.

Zhige Alu, the Yi creator god, appears repeatedly in ancient poems like The Great Flood and Forging Copper for Gods, crafting heavenly pillars and earthly beams from copper, even using it as a divine conduit.

Sanxingdui’s bronzes—sacred trees, bird-footed vessels, gold-faced figures—feature unique shapes, massive scales, and “split-mold assembly casting,” perfectly matching Yunnan’s copper craft system.

In Wenshan and Zhaotong, Yunnan, “torch copper god” worship persists today. Yi traditional faith holds that “copper is the thunder god’s bone,” and bronze is for heavenly sacrifices—never for mundane use, only for ancestors, sky gods, and tribal leaders.

Sanxingdui’s pits brim with ritual bronzes, not daily wares, confirming shared purposes. Sacred trees, copper humans, copper beasts—vessels align, rituals echo.

Crucially, no local copper mines exist at Sanxingdui. Where did it come from? From northeastern Yunnan, along the ancient Copper Horse Trails, crossing the Hengduan Mountains to the Chengdu Plain.

This copper carried not just techniques, but faiths, systems, totems, and power. In the Central Plains, copper meant weapons; in Sanxingdui and Yi culture, it was ritual ware, a medium bridging heaven and earth.

Sanxingdui doesn’t speak outright, but its language is buried in the copper, wrapped in the hair, etched on the vessels. Yet the site’s mists remain thick—its rise, flourishing, and vanishing still lack clear answers.

Whoever deciphers it edges closer to the origins of Chinese civilization. The Yi don’t claim center stage, but the historical key in their hands is already turning in the lock.