Origins of “China”

The name “China” may seem straightforward today, but its story stretches back millennia. Contrary to common belief, “China” was not always the nation’s name. Its earliest usage appears in historical texts and artifacts, reflecting a long evolution from a regional kingdom to a modern global power.

He Zun Bronze and the Western Zhou

The first known appearance of “China” is on the He Zun, a Western Zhou bronze vessel from the 11th century BCE. Unearthed in 1963 in Shaanxi, the vessel contains a 122-character inscription, including the line:

“I shall dwell in this China, and from here govern the people.”

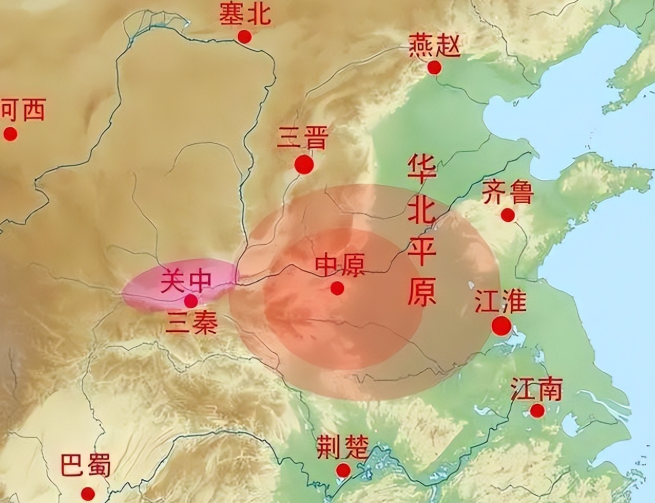

At the time, “China” referred to the Zhou royal domain, likely around Luoyang or the Central Plains. The term signified both geographic centrality and cultural authority, distinguishing the Zhou from surrounding “barbarian” tribes. Scholars initially misattributed this inscription to the Han Dynasty, but further analysis confirmed its Western Zhou origin. The vessel demonstrates how early rulers used the concept of “China” to assert legitimacy and centrality.

Other contemporary texts, including the Book of Documents (Shangshu), reinforce this notion, emphasizing Zhou ritual, governance, and the cultural identity that underpinned the term.

Qin and Han: Expanding the Realm

During the Eastern Zhou period, “China” was largely confined to the Central Plains. The Warring States era saw regional rulers invoke the term to assert legitimacy. With Qin Shi Huang’s unification (230–221 BCE), the first imperial China emerged. While initially linked to the ruling dynasty, the concept gradually expanded through centralized administration and county systems, laying the foundation for a unified Chinese identity.

The Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) further solidified “China” as a national designation. Emperor Wu (Liu Che) extended borders via military campaigns and opened trade through the Silk Road. The term “China” now encompassed assimilated peripheral regions, fostering a sense of shared cultural identity among diverse ethnic groups.

Sui, Tang, Song, and Multi-Ethnic China

Even during periods of division, such as the Wei-Jin and Northern-Southern dynasties, “China” remained associated with central regimes. The Sui and Tang dynasties reunified the region, and the term expanded alongside multi-ethnic integration, including Turks and Uyghurs. The Song Dynasty navigated threats from northern regimes while maintaining the concept of “China” as the cultural and political core.

Minority dynasties, including the Liao, Jin, and Yuan, adopted the label in official edicts, often distinguishing themselves from neighboring “barbarians,” demonstrating the term’s enduring legitimacy and adaptability.

Ming, Qing, and the Path to Modern Nationhood

The Ming Dynasty restored Han rule, emphasizing the term “Zhonghua” to assert cultural centrality. The Qing Dynasty, though established by the Manchus, continued using “China” in diplomacy, including the 1842 Treaty of Nanking. By this period, “China” had shifted from a dynastic label to a concept of nationhood.

The 1911 Xinhai Revolution replaced the Qing with the Republic of China, retaining “China” as a core identity. In 1949, the People’s Republic of China emerged, encompassing mainland China, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. Over time, “China” evolved from a narrow royal heartland to a modern sovereign state, now home to 1.4 billion people and the world’s second-largest economy.

Cultural Significance and Legacy

Why “China”? The term reflects geographical centrality (“Zhong”) and the notion of a unified state (“Guo”). The Huaxia civilization originated in the Yellow and Yangtze river basins, with early dynasties like Xia, Shang, and Zhou laying the cultural foundation. Over centuries, dynasties integrated multiple ethnic groups, making “China” an inclusive symbol of shared heritage.

Globally, the name derives from the Qin dynasty, spreading via the Silk Road and Portuguese accounts. Jesuit Matteo Ricci’s late-Ming writings further popularized it in Europe. Beyond nomenclature, “China” embodies millennia of culture—Confucianism, Daoism, ritual systems, and philosophical thought continue to shape identity.

Modern China blends this heritage with contemporary achievements. Economic reforms, high-speed rail, 5G technology, and global influence illustrate how historical roots underpin progress. Understanding the evolution of “China” fosters a deeper sense of continuity and cultural pride.

References

Based on historical texts like Shangshu and archaeological finds such as the He Zun; general knowledge from Chinese historiography.