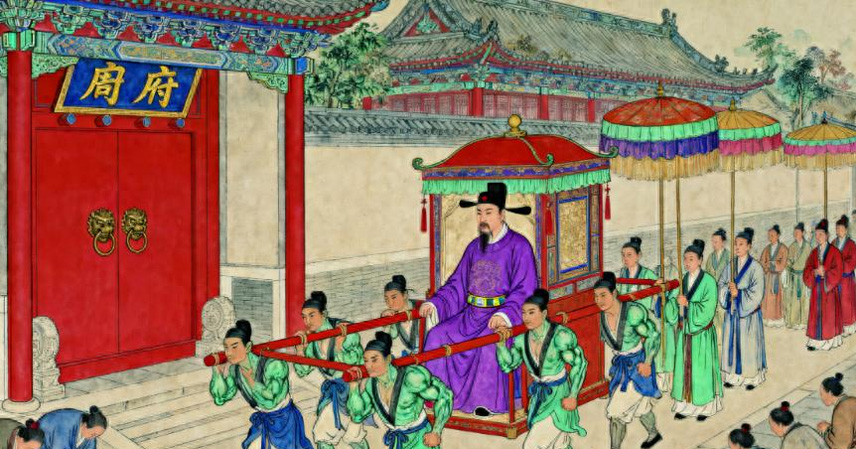

In the Yongle era of the Ming Dynasty, the Zhou family in Shangyuan County, Yingtian Prefecture, was a name synonymous with prestige. Their sprawling estate covered over a hundred acres, adorned with ornate beams and painted rafters, golden bricks paving the grounds, and dozens of maids and servants bustling about. When the master went out, he rode in an eight-carrier sedan, exuding unmatched grandeur. Yet no one could have foreseen that this dazzling Zhou household would crumble into ruin within just twenty years, its descendants scattered to the winds. The root of it all lay in five acts of moral transgression by Zhou Shichang that eroded his yin virtue.

I. Embezzling Charitable Funds: Profiting from Desperate Lives

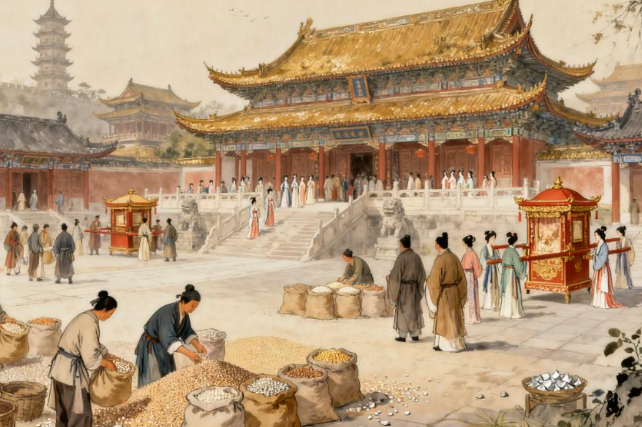

In the twelfth year of Yongle (1414), Yingtian Prefecture suffered a severe drought. Fields cracked open, harvests failed utterly, refugees swarmed the outskirts, and countless starved to death. The prefect, moved by the plight, organized relief efforts, urging local merchants to donate silver and grain. As the wealthiest man in the area, Zhou Shichang was thrust to the forefront. He publicly pledged five thousand taels of silver with apparent generosity and even volunteered to oversee the distribution of relief grain, earning widespread praise from the people and effusive commendations from the prefect.

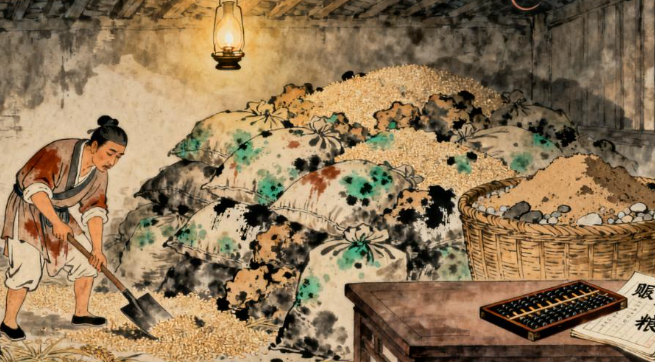

But behind the scenes, Zhou harbored sinister intentions. He had his men pull moldy old grain from the warehouses, mix it with sand and pebbles, repackage it as fresh, and dole it out to the refugees. Starved and desperate, the refugees grabbed whatever they received, boiling it into porridge without inspection. Many soon suffered violent vomiting and diarrhea, some even perishing from it. As for the donated silver, Zhou pocketed most of it, handing over only a thousand taels to the prefect while claiming the rest had gone toward procuring grain.

One refugee, an old man named Chen Laoshuan, had fled to Yingtian with his family of five. After much hardship, they finally received a ration from the Zhou household. His young grandson, famished for days, devoured two bowls of the sand-laced porridge. That night, the boy writhed in agony, convulsing uncontrollably. Clutching his grandson, Chen begged at Zhou’s gate for a few coins to see a doctor. But Zhou not only refused—he ordered his retainers to beat the old man and eject him, snarling, “You wretched beggars should be grateful for scraps! How dare you demand silver? Ungrateful scum!” Soon after, the grandson breathed his last. Chen, heartbroken, seethed in helpless rage.

A wandering monk learned of the affair and sought out Zhou. “Benefactor,” he admonished, “relief work is a path to accumulating merit. How can you defy your conscience by skimming donations and passing off fakes? Embezzling charity and squeezing blood money from the dying is the gravest assault on yin virtue. Do it too often, and you’ll squander your own blessings, dooming your descendants as well!”

Zhou scoffed dismissively. “Spare me your alarmist drivel, old monk! I’ve got silver to spare—what’s a little lost merit? My heirs will wallow in endless luxury!” The monk shook his head in sorrow, murmuring, “Good and evil will be repaid in kind; take care, benefactor,” before departing.

II. Seizing an Ancestral Home: Betraying a Lifesaver

Zhou Shichang had risen from abject poverty, orphaned young and sustained by the kindness of his neighbor, Zhou Guangdou, a humble carpenter of honest character. Guangdou not only fed the boy but taught him to read and write. When Zhou later ventured afar to seek his fortune, Guangdou handed over his lifetime savings of fifty taels as startup capital. Overwhelmed with gratitude, Zhou swore eternal repayment.

Yet once prosperity dawned, Zhou cast those vows aside. Guangdou’s son, Zhou Mingyuan, married, swelling the household until their modest home grew cramped. They planned to renovate the adjacent ancestral abode. Zhou Shichang had long coveted that plot to expand his estate, but Guangdou steadfastly refused, insisting it was the family legacy he couldn’t squander.

When persuasion failed, Zhou turned to coercion. He secretly had men tunnel beneath the foundations, cracking walls and threatening collapse. Desperate, Guangdou confronted him, only for Zhou to deny involvement: “The house crumbled on its own—what’s that got to do with me? Be smart and sell it; I’ll even toss in some silver!”

Outraged, Guangdou sought justice in court, but Zhou had already greased the officials’ palms. Not only did the case fail, Guangdou was beaten and fell gravely ill. Bedridden, he reflected on his past generosity against Zhou’s perfidy, his heart pierced with sorrow. Days later, he died in bitter resentment.

Zhou seized the property, enlarging his mansion, oblivious to how deeply this eroded his yin virtue. Servants whispered of hauntings since the expansion—eerie cries echoing at night. Zhou dismissed it as gossip, dismissing the talebearers.

III. Peddling Fake Medicine: Trampling Lives for Profit

As his enterprises grew, so did Zhou’s ambitions. Eyeing the lucrative drug trade, he opened “Jishi Hall,” touting cures for all ailments with no deceit. In truth, to cut costs and maximize gains, he peddled counterfeits: bogus herbs for genuine, cheap fillers for rarities.

Veteran physician Li Langzhong, renowned in Yingtian for his skill and integrity, bought samples from Jishi Hall. Dismayed to find them laced with subpar or even toxic plants, he warned Zhou: “Mr. Zhou, medicine heals the sick—how can you sell fakes? This endangers lives! If someone dies from your potions, no fortune can atone for your crime!”

Zhou bristled and threatened: “Mind your own business! My shop’s my affair. Keep meddling, and you won’t last in Yingtian!” Undeterred, Li posted warnings at his own expense outside the hall, but skeptics flocked in anyway.

Tragedy struck soon. Scholar Wang Xiushi, gravely ill, had his family fetch remedies from Jishi Hall. Instead of recovery, his condition worsened fatally. Enraged relatives sued with the drugs as evidence, but Zhou’s bribes turned the tide: officials deemed them genuine, blaming Wang’s death on severity alone. The matter fizzled.

Whispers spread as more victims emerged. Once exposed, Jishi Hall emptied; Zhou shuttered it, but his heartless profiteering from peril stained his name across Yingtian.

IV. Abandoning Wife and Son: A Heart of Stone

Zhou’s first wife, Lady Liu, was a virtuous, hardworking soul from his rural days. Through his darkest hours, she stood by him—cooking, cleaning, tending his ailing mother until her passing while he wandered abroad.

Prosperity bred contempt: Zhou scorned her lowly origins and plain looks, chasing courtesans. He fell for the enchanting dancer Liu Yan, eloquent and alluring, and despite Lady Liu’s pleas, installed her as principal wife, banishing Liu and their son Zhou Mingxuan to a remote corner of the estate.

Lady Liu swallowed her bitterness, pinning hopes on Mingxuan’s future. But Zhou starved them of funds and schooling; Liu Yan tormented them further, withholding food and heaping labors.

Once, Mingxuan accidentally shattered Liu Yan’s prized vase; she had retainers thrash him bloody. Cradling her battered boy, Lady Liu implored Zhou, who snapped: “His clumsiness earned it! Bother me again, and you’re out!” Her spirit shattered; this was no longer the man who’d vowed fidelity.

Malnutrition and despair felled her soon. Mingxuan begged at Zhou’s threshold for a healer, ignored utterly. Lady Liu died in torment; Mingxuan, devoured by grief, nursed undying hatred.

V. Grave Robbing for Treasure: Disturbing the Dead

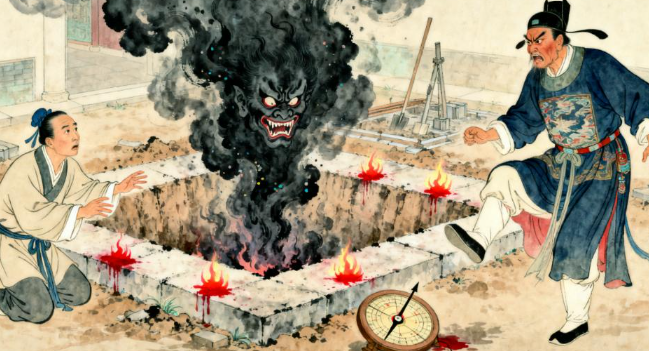

Insatiable, Zhou sought quicker riches. An old servant mentioned a suburban ancient tomb brimming with burial goods ripe for sale. Eyes gleaming, Zhou dispatched scouts and plotted the heist.

The servant pleaded: “Master, tomb raiding defies heaven, rousing restless spirits and slashing yin virtue—don’t!” Zhou barked: “Shut it! For profit, I’ll dare anything. Help or get out!” Reluctantly, the servant complied.

That night, Zhou and retainers pried open the tomb with tools. Amid dust and murals, candlelight revealed gold, jewels, and bronzes. As they loaded up, torches snuffed out, plunging them into blackness. Wails pierced the void; retainers fled in terror.

Zhou withered thereafter, felled by stroke and bedridden. Liu Yan, seeing him ruined, fled with the remnants of his wealth.

He grew erratic, haunted by nightmares. Exorcists failed; businesses crumbled—pawned goods stolen, silks spoiled, profits evaporating. Zhou perished soon. Mingxuan vanished abroad, never returning. The once-mighty Zhou estate stood hollow, a relic of sighs over tea.

The tale endured in Yingtian, a warning: Zhou’s five sins each chipped at his yin virtue, cursing him and his line—a textbook case of retribution. Elders still invoke it to counsel the young.

As the editor, I’d add: In life, shun embezzling aid, seizing homes, hawking fakes, ditching kin, or looting graves—these defy ethics and law, harming others while dooming yourself and family to irredeemable woe. Virtue rebounds; cling to morals and justice, be kind and upright. Share your thoughts in comments, and feel free to like, save, or repost.