The term “South Korean chaebol” carries a whiff of money and power intertwined, and Lotte Group epitomizes this. From its humble beginnings to its current stature, Lotte has weathered storms but repeatedly crossed red lines, tarnishing its reputation.

Lotte’s founder, Shin Kyuk-ho (born in 1921 in Ulsan, South Korea, then under Japanese colonial rule), came from a modest rural family. As the eldest son, he shouldered responsibilities early. Around 1941, he secretly left for Japan with little money, seeking opportunities in the colonial power’s heartland.

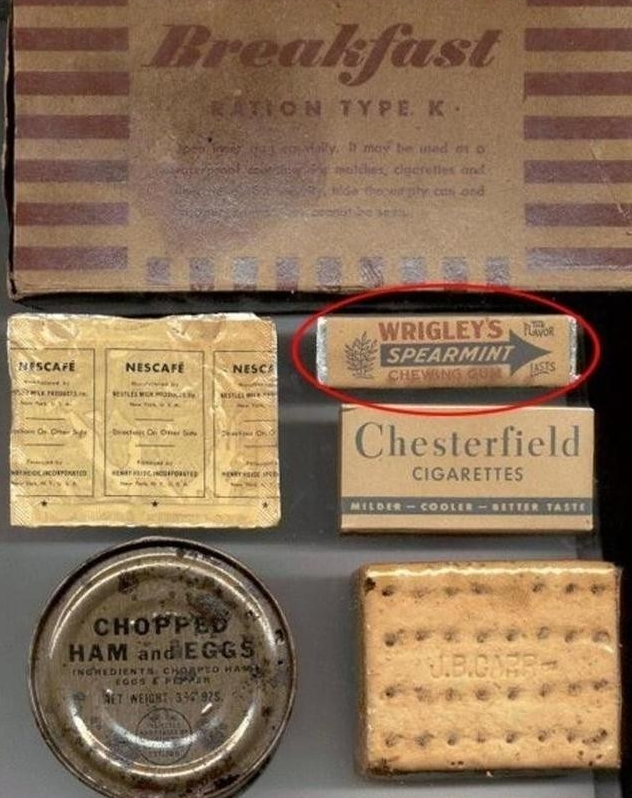

In Tokyo, he took odd jobs—delivering milk and newspapers—to scrape by. During World War II, the soap factory where he worked was bombed by U.S. forces. He survived by chance, being off work that day. Post-war, with Japan’s surrender, he worked for U.S. occupation forces, moving supplies and observing their habits, like chewing gum, a novelty in Asia at the time.

In 1946, Shin started making chewing gum, using recipes learned from the Americans. Early batches didn’t impress U.S. buyers, but they appealed to Japanese tastes. He tweaked the formula, and by 1948, he founded Lotte Co., Ltd. in Tokyo, the precursor to Lotte Group. From gum, he expanded into chocolates and biscuits.

In the 1950s, as South Korea’s economy took off, Shin seized the moment. After Japan and South Korea normalized relations in 1965, he moved Lotte’s operations back to Korea. With government support, Lotte grew rapidly, branching into retail, hotels, chemicals, and food, becoming one of South Korea’s top five chaebols through acquisitions and investments in malls and factories.

Shin Kyuk-ho was a tough operator, managing a multinational empire with thousands of employees and vast cash flows. Yet, scandals brought him down.

Lotte’s brazenness is evident in its exploitation of celebrities. In 2009, South Korean actress Jang Ja-yeon took her life at 29. Her suicide note named multiple corporate executives, alleging she was forced into providing sexual services over a hundred times. Jang, who had appeared in Lotte ads, implicated Lotte figures, including Shin and his sons. The case exploded in the media, with netizens uncovering details of her ties to Lotte. Police investigations stalled due to insufficient evidence, and Lotte’s legal team delayed proceedings. The case fizzled out, with Lotte escaping with only reputational damage, continuing business as usual.

This exposed the dark side of South Korea’s entertainment industry, where chaebols wield power to exploit. The Jang case became a symbol, yet implicated companies faced little real punishment. Lotte’s attitude—seemingly untouchable due to its wealth and influence—ignored public outrage.

Then there’s the issue of controlling presidents. In 2016, President Park Geun-hye was embroiled in a corruption scandal involving her confidante, Choi Soon-sil, who controlled foundations receiving corporate donations. Lotte’s chairman, Shin Dong-bin (Shin Kyuk-ho’s second son), donated 7 billion KRW to Choi’s foundations, securing government approval for Lotte’s duty-free store expansion. Prosecutors found the funds directly benefited Park, giving Lotte favorable policies. In April 2017, Shin Dong-bin was charged with bribery. Despite his denials, evidence was clear. In December 2017, he received a suspended sentence, but in February 2018, a higher court sentenced him to 2.5 years in prison. He served a few months before being released in October 2019 after the Supreme Court upheld the verdict.

This wasn’t just Lotte—Samsung and other chaebols were also implicated in Park’s scandal, exposing South Korea’s crony capitalism. Chaebols donate for policy favors, presidents loosen regulations, and the public pays the price.

Lotte’s most audacious move was provoking China. In July 2016, South Korea and the U.S. announced the deployment of the THAAD missile system, with Lotte’s Seongju golf course chosen as the site. On February 27, 2017, Lotte’s board approved the land swap for the base. China, viewing THAAD as a threat to its security due to its radar capabilities, reacted strongly. From March 2017, Chinese consumers boycotted Lotte, protesting outside stores. Lotte Mart stores faced fire safety inspections, leading to nearly two dozen closures. Consumers switched to local brands, Lotte products were pulled from shelves, and the group lost billions. Despite injecting 360 billion KRW, the damage was severe. Lotte’s Chinese websites were reportedly hacked, paralyzing operations.

Lotte underestimated China’s market sensitivity. Already struggling in China, the THAAD decision was catastrophic. By 2018, Lotte began closing stores, and by 2022, it fully exited China, shifting to Southeast Asia. This misstep—supporting a government military move—cost Lotte dearly, revealing chaebol shortsightedness in global politics.

Lotte’s behavior stems from South Korea’s chaebol system. Post-World War II, government-backed conglomerates like Lotte drove economic growth, controlling key sectors. Presidents rely on them for jobs, while chaebols seek policy favors, creating a cycle of corruption, as seen in Park’s case.

Internally, Lotte’s chaos added fuel. In 2015, with Shin Kyuk-ho aging, his sons, Shin Dong-joo and Shin Dong-bin, fought for control, ousting each other in boardroom battles and lawsuits. Shin Dong-bin prevailed in 2016, but mismanagement lingered. Shin Kyuk-ho died on January 19, 2020, at 98, with a low-key funeral amid ongoing family disputes.

Lotte’s boldness traces back to Shin Kyuk-ho. Starting in Japan, marrying a Japanese wife, and running dual headquarters gave Lotte flexibility. Critics claim Shin leveraged ties to a Japanese war criminal’s family, though details are murky. Back in Korea, Lotte dominated markets, its size and tax contributions shielding it from government action.

The Jang case slipped away due to weak evidence and legal gaps. Bribery paid off until the scandal’s scale overwhelmed Lotte’s calculations. The THAAD fiasco, meant to curry government favor, backfired with China’s economic retaliation, slashing Lotte’s revenue and morale.

As of 2025, Lotte is restructuring. In July, Shin Dong-bin led a two-day strategy meeting, pushing reforms amid crises. Lotte Corporation’s stock fluctuates, with Q2 2025 sales at 4.1971 trillion KRW but operating losses. Spanning food, retail, and chemicals across 120+ global companies, Lotte’s China exit still stings, and Southeast Asia growth is slow. Ranked fifth in Korean assets (over 90 trillion KRW), land revaluations mask operational struggles. A 2025 data breach at Lotte Card further dented its reputation. Global hiring, like Vietnam job fairs, continues, but family control overshadows professional management.

Conclusion

Lotte’s saga shows chaebols aren’t invincible. Wealth can settle small issues, but crossing international lines has consequences. China’s boycott humbled Lotte, forcing a pivot to other markets, though scars remain. South Korea pushes chaebol reforms for transparency, but progress is slow. Lotte’s arrogance, rooted in systemic protection, led to its stumbles. Shin Kyuk-ho’s rise from poverty to empire was legendary, but family feuds and scandals marred his legacy. Shin Dong-bin drives investments post-release, but shrinking market share and competition keep Lotte subdued, its future hinging on transformation.

References

- The Korea Times, articles on Lotte’s THAAD involvement and Park Geun-hye scandal (2016–2019).

- Jang Ja-yeon’s suicide note and related media reports (2009).

- Lotte Group financial reports and press releases (2025).

- South Korean court records on Shin Dong-bin’s bribery case (2017–2019).